James Petras, man, and Michael Parenti, and now Jesse Jackson — rest in power

Feb 17, 2026

On May 15, 2019, Rev. Jesse Jackson broke the siege of the Venezuelan embassy in Washington to deliver food and supplies to antiwar activists defending it from the Trump admin and its violent proxies among the fake Juan Guaido mafia it had recognized as Venezuela’s government.

Jesse took this physical risk and stood for international law while afflicted with Parkinson’s, which had forced him to dial back his famously frenetic schedule.

Best known as a civil rights activist and understudy of MLK Jr., Jesse Jackson was also a diplomat who leveraged his status and personal gravitas to secure the release of Navy Lt. Robert Goodman, whose plane was shot down while attacking Lebanon, through in-person negotiations with Syrian Pres. Hafez Al-Assad.

Jesse was the first major Democratic presidential candidate to recognize the PLO and force the issue of Palestinian statehood. He campaigned against the criminal US embargo of Cuba, led grassroots opposition to apartheid South Africa, and spoke at the funeral of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez.

His geopolitical chops were on display during the 1984 and ‘88 primary debates, demonstrating a command of international issues that would have put any of today’s leading Democrats to shame. Jackson’s two presidential campaigns paved the way for those of Bernie Sanders, who proved more malleable and milquetoast on foreign policy.

Barack Obama considered Jesse a threat to his bid to win over the Zionist lobby and suburban white swing voters. And Jesse privately (and once on a hot mic) recognized Obama as a hollow fraud who would spend more time lecturing Black America than delivering material results for it.

With the backing of Wall Street and the war state, Obama supplanted Jackson, ensuring that there would no longer be a place for his brand of politics within the Democratic Party. Indeed, there is no contemporary successor to Jesse Jackson within the party, only the corporate misleaders and progressive pretenders now memorializing a whitewashed version of his legacy.

And here is the Semen Drip Rapist:

The Russian model Ruslana Korshunova, according to declassified files, visited Jeffrey Epstein’s island in 2006 when she was still 17 years old… just 2 years later, she fell from the 9th floor of an apartment building where she lived in New York.

Remember the case of Dusti Rhea Duke, a girl who was only 14 years old when she was abused by Trump… 5 years after the abuse, she gathered the courage to report him for rape to the police and 2 weeks after filing the complaint… Dusti was found “suicided” with a gunshot to the head. in Kiefer, Oklahoma.

She is not the first girl connected to Epstein’s pedophilia network who has appeared suicided under strange circumstances.

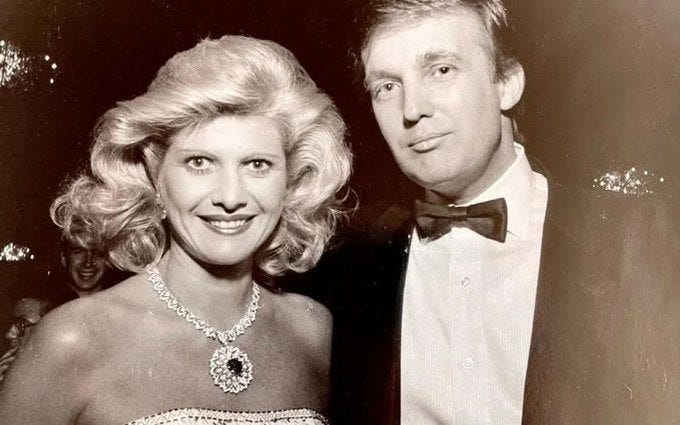

Trump’s first wife, Ivana Zelníčková, fell down the stairs and died just a week before she was supposed to testify against Trump.

She is buried on a golf course; her grave is overgrown with weeds, and no one ever visits it.

For some reason, that doesn’t surprise anyone at all…

For his 1993 book, “The Lost Tycoon,” Harry Hurt III acquired Ivana’s divorce deposition, in which she stated that Trump raped her.

In fact, women have been making allegations that Donald Trump has sexually assaulted or harassed them for decades, including in sworn court filings. Some of the behavior women have described to reporters closely parallels Trump’s own characterization of his conduct in a recently unearthed 2005 recording.

“I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait,” he told then-”Access Hollywood” host Billy Bush. (Access Hollywood is owned and distributed by NBCUniversal, the parent company of NBC News and MSNBC.) In the tape, Trump brags bout how being a star means “you can do anything,” including “grab them by the pussy.”

Related: Four Women Accuse Trump of Inappropriately Touching Them Years Apart: Reports

Other charges against Trump are substantially more serious. In a deposition taken during their divorce proceedings in 1989, Ivana Trump, the mother of Trump’s three eldest children, said he raped her, but when it was reported on again last year, she said “the story is totally without merit.” A set of claims from a Jane Doe, who alleges Trump raped her in 1994, when she was 13, is pending in federal court. Trump’s attorney has called that accusation “categorically untrue and an obvious publicity stunt aimed at smearing my client.”

On Thursday, Trump said at a rally, “These vicious claims about me of inappropriate conduct with women are totally and absolutely false,” and promised to present “substantial evidence to dispute these lies.”

Here are the allegations that have been publicly made against Trump, from oldest to newest, as well as his or his campaign’s responses to the claims. NBC News has also reached out to these women individually. None of these allegations have been independently verified by NBC News.

Yoga instructor and lifestyle coach Karena Virginia alleged that Trump and other men approached her as she waited for a car service at the U.S. Open tennis tournament in Flushing, New York, and that Trump touched her right breast.

“I was quite surprised when I overheard him talking to the other men about me. He said, ‘Hey, look at this one, we haven’t seen her before. Look at those legs.’” Virginia said at a press conference with women’s rights lawyer Gloria Allred. “As though I was an object, rather than a person.”

“He then walked up to me and reached his right arm and grabbed my right arm, then his hand touched the right inside of my breast. I was in shock. I flinched,” she continued.

She said Trump then asked her, “Don’t you know who I am? Don’t you know who I am?” Virginia said that for years afterwards she blamed herself because she was wearing a short skirt and heels.

Allred served as an elected delegate for Clinton during the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in July.

+—+

Real HERO:

Petras held the tiller firm after the early 80s, insisting that class struggle analysis was fundamental, and refusing the conceits of respectable academia along with the controlled opposition of the NGO industrial complex and its professional cadres.

Professor James Petras, 89, world-renowned sociologist, public intellectual, and scholar of Latin American politics and global economics, died peacefully on January 17, 2026, in Seattle, WA, surrounded by family. A prolific scholar and activist, he devoted his life to challenging power, imperialism, and inequality.

Born January 17, 1937, in Lynn, MA, Professor Petras was a Greek American who earned his B.A. from Boston University and Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. Joining Binghamton University in 1972, he became Bartle Professor of Sociology, a Professor Emeritus, and an adjunct professor at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax. His Greek immigrant working-class upbringing shaped his lifelong dedication to class struggle, inequalities, and marginalized communities. Over decades of teaching, he mentored generations of students who went on to become scholars, activists, and community leaders.

Petras was an uncompromising voice for social justice across the Americas, Europe and the Middle East. His life’s work bridged the classroom, the written word, and the struggles of workers, peasants, and social movements, leaving a powerful intellectual and moral legacy. Petras was renowned for the breadth and volume of his writing, becoming one of the most prolific critical sociologists of his generation.

He authored over 62 books, translated into 29 languages, and published hundreds of academic articles in leading journals such as the American Sociological Review, British Journal of Sociology, Social Research, Journal of Contemporary Asia, and Journal of Peasant Studies. He reached the broad public through more than 2,000 essays in outlets including The New York Times, The Guardian, The Nation, The Monthly Review, The New Left Review, Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, Partisan Review, Canadian Dimension, Le Monde Diplomatique, La Jornada, his official website: https://petras.lahaine.org/ and https://radio36.com.uy

His books were published by major presses including Random House, Wiley, Routledge, Macmillan, Verso, Zed Books, Pluto Press, and Clarity Press, reflecting the global impact of his ideas.

A leading expert on Latin American politics, he examined how neoliberalism, transnational capital, and U.S. foreign policy impacted society and political resistance movements, producing influential works including: Unmasking Globalization: Imperialism of the Twenty-First Century (2001); The Dynamics of Social Change in Latin America (2000), System in Crisis (2003), co-author Social Movements and State Power (2003), Empire with Imperialism (2005), co-author Multinationals on Trial (2006) and Rulers and Ruled in the U.S. Empire (2007).

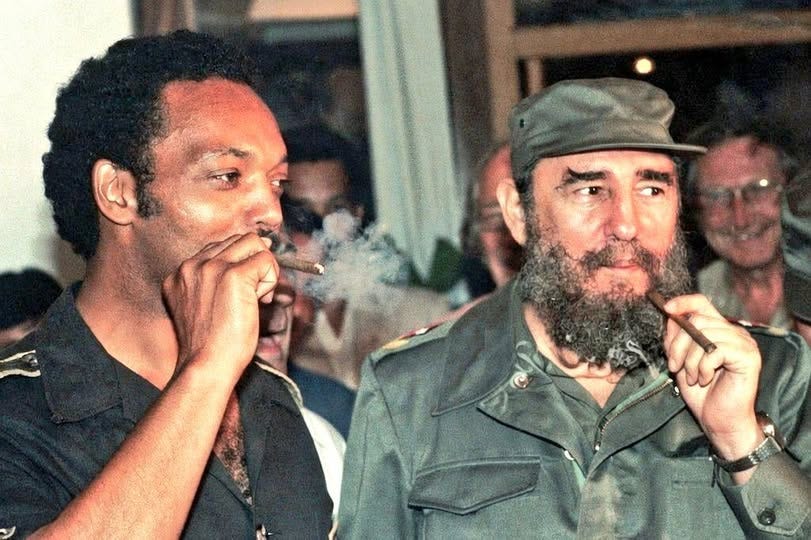

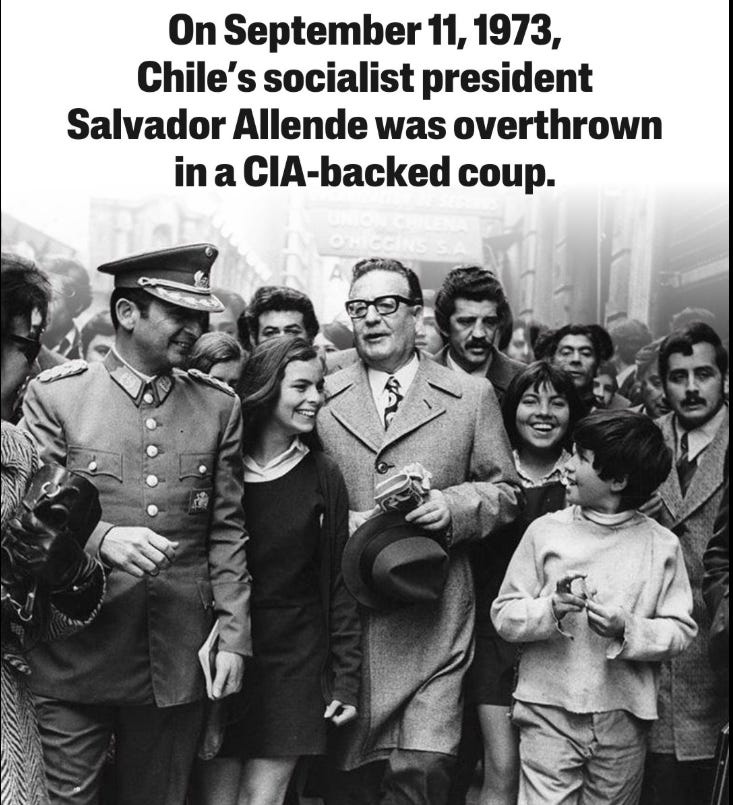

Beyond academia, Petras engaged with leaders including Salvador Allende in Chile, Andreas Papandreou in Greece, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, and met with Fidel Castro in his later years. His commitment to social justice includes 11 years of work with the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement. In 1973-1976, he was a member of the Bertrand Russell Tribunal on Repression in Latin America. He believed that scholarship should support the struggles for justice, which influenced both his teaching and his extensive public engagements.

His distinguished career earned honors such as the Best Dissertation Award from the Western Political Science Association, the Lifetime Career Award from the American Sociological Association’s Marxist Sociology Section, and the Robert Kenny Award for Best Book.

Outside his scholarly life, he was a devoted father and grandfather, sharing his love of the Red Sox baseball team with his children, an avid fisherman who brought home stamps and coins from around the world. He enjoyed simple living, playing games and creating a robust garden for food consumption and the beauty of flowers. He is survived by Professor Elizabeth Petras, Stefan Petras, Anthippy Petras, Wendy Petras, Liam Petras, and Xana Petras-Roper. His collaborators and dear friends include Henry Veltmeyer, Morris Morley, Fred York and many, many more. James Petras is remembered with deep respect by students, colleagues, comrades, and readers worldwide for his fierce intellect, moral clarity, and enduring faith in social transformation.

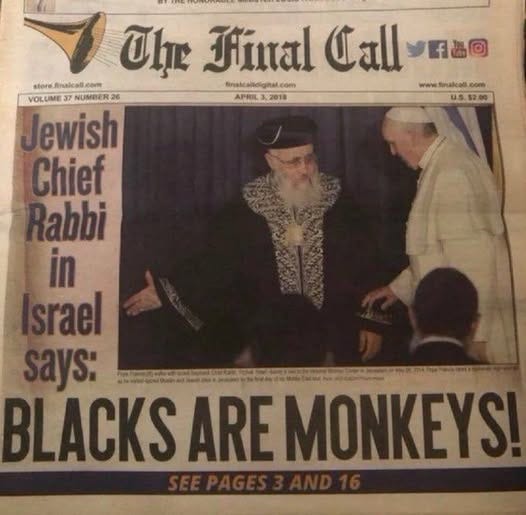

James Petras talks to Hesham Tillawi about Israel’s power in the United States, the title of his latest book. Jewish control of the Media, Banking, and Congress. AIPAC

Norman Finkelstein exposes himself as a Zionist in a debate with James Petras

Comments:

“Hagit Borer definitely has a Blindspot when it comes to criticizing anything Jewish.

She owes Petras an apology.”

“Finklestein is a brave and good man, but his bias is blatant and results in some of his views just being plain wrong. Petras exposes this.”

Interview with James Petras: Neoliberalism and resistance

6 May 2009

FRFI

James Petras is a revolutionary, anti-imperialist activist and writer, who has worked with the Brazilian landless workers’ movement and the unemployed workers’ movement in Argentina. He gave this interview to Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! on 21 March 2003.

FRFI: What is the strategic importance of Latin America for the US, particularly in the present circumstances?

Well let’s deal with the phoney arguments that say Latin America’s percentage of world trade has been declining; its importance for the US economy as a whole, as a percentage of its world trade, has been declining, so it is not very important. These are generalised arguments with inappropriate comparisons. It is important to note that Latin America is the area where the US banks get the highest rates of return and where historically they have received the greatest part of their overseas earnings. Banks like Citibank and Bank of America have been enormously successful in transferring illegal funds from Latin America, amounting to tens of billions of dollars every year. In addition Latin America is the only region in the world where the US has favourable external accounts balance of payments, so it helps to compensate for the enormous deficits it has in Asia and even in Europe. From that vantage point, if the US did not have Latin America the dollar would be weaker and its external accounts would be in even worse shape than they are right now.

There are other factors apart from its significant global strategic importance. Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, and Argentina are all oil-producing regions and provide an important source of petroleum to the United States, particularly in times of crisis in the Middle East. The US has in Latin America, usually, a solid bloc of votes which it is able to mobilise to counteract opposition in other regions. There is also the fact that the US corporations in Latin America, particularly the 500 biggest corporations in the United States, control significant parts of the Latin American economy, and I don’t just mean industry and raw materials. I mean fast food, real estate, tourism, air traffic etc. You have a whole array of important strategic sectors of the US multinationals and banking which are able to appropriate profits, interest payments and royalty transfers, that help bolster sagging positions within the United States. For all these reasons, I think Latin America is extremely important. The concern particularly with Colombia, but Venezuela also, has to do precisely with the fear that a successful social transformation would have a demonstration effect on the rest of Latin America. It would undermine this notion that it is not possible to carry out change under the so-called conditions of globalisation, which has become one of the main arguments for all sorts of fake left and reformist people who say: ‘Well yes of course we should forget about the debt, of course we should fight neo-liberalism, but let’s be realistic, how far can we go given the power and dominance of the US?’ Or again they use this very amorphous term ‘globalisation won’t allow it’. I think the struggle in Colombia is precisely over the attempt by the United States to prevent that invincibility myth from being eroded.

FRFI: Could you say something about the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which is being planned in this context?

First let’s look at what has happened in the last decade. The 1990s was a decade that was horrible for Latin America in every sense of the word. Income declined, poverty increased, the biggest economies went belly up and Brazil had the worst growth record in its modern history. On the other hand, for US investors, bankers, industrialists and telecommunications, it was the golden age. Never did they take out so many profits, never were so many public firms handed over to monopolies, never were they able to enforce so much interest transfers, never were they able to ship out so much illicit earnings through their financial circuits because of the deregulation of financial markets. Now, this golden age isn’t enough. Washington wants it all and I think a lot of thinkers are mistaken in underestimating the voracious appetite of US imperialism.

Two things have to be kept in mind. One is that extremely lucrative sectors of the Latin American economies still are in the public sector, largely because of mass trade union struggles. I’m talking about the petroleum industry, electrical power and light industries in Ecuador and in Mexico. I’m talking about some of the minerals, gas and oil in Bolivia and several other strategic sectors which they haven’t been able to privatise because of enormous worker resistance. The same is true in Colombia, some of the public utilities held back. So FTAA will fashion a framework in which the rules it sets will supersede national legislation on public-private divisions. Secondly, and more importantly, the principal backers of the current neo-liberal policies have lost support. They are no longer able to mystify the population; they are totally discredited. That group of political clients of the US in the 1990s are totally discredited everywhere. Toledo [in Peru] gets elected and within six months he is down to single digit support. Sanchez de Lozada [in Bolivia] is barely holding on to power and the betting is that he doesn’t last out his regime.

There is fear that this golden egg that they have been hatching every year is going to be lost, so they want to go beyond the nation state where the pressures are enormous, to set up a commission of free trade, in Miami probably, run by a US official or a notable client, where they don’t have to worry directly about legislators and local officials or mass movements. They will be immune to those direct pressures. So the free trade area will be multi-purpose. It is a further stage that goes from neo-colonialism to outright colonialism. Sovereignty is totally dissolved in this supra-national entity which is simply another arm of US imperialism. The US government will have the dominant influence. Along with this free trade area you need some mechanism to sustain the decisions and implement them against forceful majorities and that is why US military bases are being set up, joint training exercises and further deepening involvement through the Plan Colombia initiative or the Andean initiative etc.

There is one further embellishment to this and I think this is probably a bit more controversial. With the disintegration of the older generation of neo-liberals, I am talking about Cardoso [in Brazil], Noboa [in Ecuador] etc, a new wave of neo-liberals disguised as social-democrats, like Lula da Silva [in Brazil], a populist, like Gutierrez [in Ecuador], are now backing the FTAA, although they want to discuss the timing and the concessions they can secure from the United States. So they are not just operating on the level of direct control, they are also working through this new wave of former leftists or populists as the new supporters. However, Gutierrez, is already facing opposition from his former allies in the Indian organisations, and Lula is already facing major challenges from metal workers and public employees for his drastic IMF austerity programme. So again this idea of having a supra-national entity is high on the agenda in Washington.

FRFI: How do you see the resistance in Latin America developing?The resistance is extremely widespread; the opposition to FTAA is enormous. I would say it involves three quarters of the population without exaggerating. I think if we look at Bolivia we see some of the most significant mass struggles today. They almost toppled Sanchez de Lozada on the day of the urban insurrection. When the police became involved he had to actually slink out of the Presidential Palace in an ambulance. Someone said he was dressed as a nurse – I don’t know if that is simply apocryphal – but the fact is that streets in cities like Santa Cruz and Cochabamba were practically taken over by the army but surrounded by huge opposition movements. They have an extraordinary leader there, Evo Morales, who has combined extra-parliamentary and parliamentary struggles in a very creative way, subordinating the parliamentary struggle to the mass struggle and creating a comando popular [popular coordinator] trying to merge the urban movements, the self-employed and progressive or class-oriented trade unions. The struggle there is extraordinarily advanced. Evo is a clear anti-imperialist, no ambiguities there, and while he embraces an autonomy for Indians and of course the legalisation of coca, he has a broader vision of a kind of Andean socialism, that is socialism adapted to the social formation of the Andean countries. Now that is one of the most advanced struggles.

Colombia is a second advanced struggle and I think we have to look at it as a multi-dimensional struggle. The big confrontation by the guerrilla movement encompasses up to 25,000, but could easily escalate to 50,000 combatants. They are extremely well armed with light weaponry and prepared by an extraordinary leadership. Manuel Marulanda is one of the great guerrilla commanders of Latin American history, comparable to Ho Chi Minh in many ways or General Giap, the famous Vietnamese. The influence of the FARC probably extends anywhere between 40% upward of the countryside. Overwhelmingly a peasant formation, over 70-80%, whose leaders are closely tied to the mass struggle. They differ from some of the commanders of Central America, petty bourgeois professionals who found it pretty easy to return to cushy seats in Parliament abandoning many of their principles. I don’t think you’ll see that kind of phenomenon in Colombia. They are a very advanced movement with very strong class roots.

The second thing about Colombia is the mass struggle and here I think we have to look at the neo-liberal policies that have radicalised the trade union movement, that have radicalised the countryside. There is an agricultural block that goes from landless workers, small peasants, middle-sized coffee growers, who are adversely affected by the ending of government subsidies and free trade policies that have resulted in the import of cheap grains and the failure to provide support for coffee. So you have a block here that has had extraordinary success in mobilising tens of thousands in opposition to this government. You have the trade union movement, the public employees, school teachers, sections of manufacturing workers and banana workers, petrol workers, who have been in head-to-head confrontations with the regime and suffered the consequences through scores of killings etc. It’s a life and death struggle. The question of state power is on the table. At least the advanced detachments of the class struggle have put the question of socialism versus capitalism on the table. I think it’s the principal concern of the United States outside of the Middle East.

I just highlighted what I think are the most advanced movements. On a secondary level, but not far behind, is the movement in Venezuela, which is very complex, very contradictory, but moving toward a clearer class polarisation. Chavez began as a kind of foreign policy nationalist, which was enough to provoke the United States. He had carried out some welfare spending programmes, on housing, on schools etc. Very minimal introduction of some progressive taxation, the beginning of taxing some part of wealth. The whole tax system in Venezuela is extraordinarily regressive, based on taxing petroleum income. Chavez’s politics is a kind of progressive Bonapartism, balancing between different internal groups, maintaining US corporate interests while also determining independent foreign policy, on OPEC, on Cuba and in relationship to Plan Colombia etc. However, after two coup attempts led by the local bourgeoisie in alliance with the US, Chavez has begun to move in some very significant ways.

First, he’s cleaned out some sectors of the pro-imperialist military, which is important for any progress in the country. Secondly, he’s moved towards a more conscious and deliberate organisation of the neighbourhoods, the Bolivarian circles. Thirdly, he’s beginning to develop a policy of creating alternative class-orientated trade union nuclei to displace the pro-imperialist trade union cabals. Most significantly he has nationalised the public enterprises. Now that sounds a bit anomalous, but these are public enterprises in which 60% of the revenue was spent on salaries. The salaries of the senior executives were between $400-500,000 a year. Most of the profits from the oil earnings were invested in CITCO in the US, a $1 billion chain of gas stations bought by the Venezuelan state enterprise. Instead of investing back into Venezuela, instead of utilising the Venezuela financial networks of the public central bank to devise the priorities for social investments, economic investments, it was going outside, it was going through US, Wall Street and financial circles. So you have the bleeding of the principle dynamic sources of investment under the name of public investment.

Now Chavez has cleaned out most of these directors and some of the so-called technical people who would sabotage the whole operation. There was a kind of ruin or rule policy. They’ve been cut off and oil is now in the hands of – at least I can say – the nationalist Ali Rodriguez, who was a guerrilla in the 1960s and a moderate nationalist today. He’s a reasonably honest fellow, who, I think has given priority to revitalising oil as a source of domestic development and eliminating at least those extraordinary salaries and other investments. This is key. If you control the oil revenue, you can finance agrarian reform, you can finance public enterprises, you can finance public development of research, social development etc. So it is an extremely important move, the first step to creating what we might call a welfare state, a social economy, a nationalist social-democratic state. And I think the dynamics there are coming from below. Chavez has been trying to conciliate classes, but under the pressures of the struggle, the blows from imperialism and the pressure from below, he’s moving in a radical direction and that’s a very important development.

In Argentina, since the 2001 uprising you had an enormous radicalisation in the middle class. And I think we should use that term in quotation marks. What we know as the ‘middle-class’, making ten to twelve thousand dollars a year in Argentina, which in Buenos Aires was something like 35% or even more of the population, has been proletarianised. Many have lost their jobs, their incomes have been cut by two-thirds and they are no longer objectively middle-class. You have a downwardly mobile middle-class approaching the living standards of the proletariat and incorporating some of the mentality of class politics, engaging in marches, uprisings, supporting the unemployed workers’ movements etc. That’s a huge change. There has been an incredible collapse in living standards and growth of poverty reaching 60% of the population. This is in a country which in 1998 had a per capita income of $9,000 a year, now falling to $2,500-$2,700 per capita, which doesn’t take into account the great disparities. You have the organised unemployed, you have the growth of these neighbourhood popular assemblies, incorporation of the lower middle-class, the collapse of capitalism, the banking swindles and loss of savings.

Objectively, it should be a pre-revolutionary situation. However, what has happened? The fundamental subjective factor is lacking, and I’m not talking about the subjectivity of individuals or groups, I’m talking about the subjectivity problem of the existing left groupings. And one might add of the piqueteros, who have developed what I would call a very sectarian conception of the revolution. Each one with their small groups, fighting the other groups to see who can win over one or another neighbourhood, to put up their flag. So there’s been an appalling lack of unity in the face of this tremendous historical opportunity and I’m not picking and choosing. I think that there is a good deal of blame to pass around to all these groups. There’s been one ideological influence that’s affected some small groups of intellectuals who have disseminated it in popular neighbourhoods and actually influenced a few leaders. It is the concept that the new revolution will happen without taking state power. John Holloway [a British academic based in Mexico], for example, says that you don’t have to struggle for state power, you just create parallel organisations at the local level and they somehow multiply themselves and eventually they’ll transform the system through some form of permeation. This is a kind of warmed over Fabianism with a certain kind of populist veneer. It is an ideology which simply codifies the limitations of some of the locally-based movements instead of helping them to develop a real class consciousness and conception. None of the local problems can ever be solved – even the most elementary problems of food and jobs – simply by devising barter relations at the local level. In other words Holloway is raising to a political principle the survival strategies that people themselves have been forced to pursue.

So all of this together has led to a situation which is extremely difficult to deal with right now. The problem is that there are elections coming up. My position has been very negative toward electoral politics in general and in particular because of all the experiences we’ve had, past and present, with the evolution, adaptation of left electoral parties to the bourgeois state, bourgeois politics. However, the question I raise – I don’t have an answer – is how much of an abstentionist vote can you get? Can you get 50% abstention? What if you only get 25%? Then what do you do if 75% of the people are going to vote, particularly in the context where the insurrection is not on the table? So you have the possibility – I’m not saying I know the story yet – that the majority of the people in the streets is going to vote. The alternative perspective of an insurrectionary politics is not on the agenda. The bourgeois parties are divided at least six ways, which means a 25% majority, which a united left could secure, is being overlooked. What do you do in that context? Do you say elections? But if you say elections and all the little groups present their candidates to get two or three per cent of the vote, that’s going to be an illustration of weakness. If you call for an abstention and only get 25-30% of the vote what do you get out of that if a fascist like Menem comes to power, a Menem who is as sinister as any death squad leader in Latin America.

So it’s a difficult situation. I would dare to say, that if the left could present a unified candidate with some credibility, it could secure a vote and put into question the whole political order as a transition to a further radicalisation. If they can secure the 40-50% abstentions then by all means, delegitimise the system. So it’s hard to make a judgement from outside. It is clear that bourgeois parties are in deep crisis. It’s clear in the most vulgar Marxist sense that the whole capitalist system in Argentina is collapsing. Nothing is working. When you get 30% of the population that has absolutely nothing to lose but their chains, and 60% living below the poverty line, a middle-class that’s downwardly mobile, a ruling class that’s divided, obviously this is what Marx talked about when he talked about the possibilities of a socialist revolution.

The first time I met Salvador Allende was in 1965 in the bar of the US

Senate building. At that ,he was a senator, and I was a graduate

student writing my doctoral dissertation and was deeply involved in the

anti-Vietnam War movement in the US. Before leaving San Francisco

for Chile, the organizers of an upcoming demonstration had asked me

to tape an interview with Senator Allende expressing his suppot for the

anti-war movement in the US. Allende’s support was particularly important for the struggle in the US because the mass base of our movement was basically composed of students, middle-class professionals and very few workers. We felt it would be important for morale to have the international support of a leftist presidential candidate who received over a million votes, mainly from the working class, peasants, and the trade unions. — (Petras, 1998)

Although the work of James Petras has encompassed many different countries, it is not far-fetched to claim that Chile has decisively shaped both his insights about social processes and commitment to popular struggles; indeed for more than four decades, that ‘ long petal of wine, sea and snow’ called Chile has been at the centre of his formation and maturation as a revolutionary intellectual. His numerous contributions to our understanding of the interconnected dynamics of capitalist development and class struggles, which over the past half century have shaped Chilean society are

impressive. However, equally admirable is that while engaging in analysis of the highest scholarly and political caliber, Petras has also consistently displayed three traits worthy of emulation, particularly at the present moment. Witnessed at first from afar as a mere student and later observed directly as one of his long-list of collaborators and co-authors, perhaps more than any other living intellectual

James Petras has embodied these three qualities that define activist scholarship:

1. the unfailing courage to submit to ruthless criticism ‘everything under the sun’ even if it means going against the grain of the cherished myths of the ruling elites, mainstream academia and even the Left itself;

2. a genuine commitment to hear grassroots activists and militants not as ‘data’ but incorporating them into an on-going dialogue as a way of ‘naming the moment’ and defining effective lines of action;

3. a permanent concern with locating specific events transpiring in concrete social formations within the broader development of capitalism on a world scale and the struggle against imperialism, and to do so without reductionism, teleological thinking or loss of finely grained uniqueness of the phenomena studied