ICE is your Gestapo, so just call in the teenagers in Mexico to train us how to fight the cartels, man, and the PIGS.

Jan 31, 2026

It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees. —Emiliano Zapata

The installation of the floating barrier is in clear violation of the U.S.-Mexico water treaty, which requires both countries to agree to any structure that can potentially divert the course of the river. For years, Mexico has filed diplomatic protests regarding violations of the U.S.-Mexico binational treaty as more wall barriers, shipping containers and other construction has taken place in the river’s floodplain.

In 2023, the Biden administration sued Texas after it installed a different chain-like type of buoy barrier near Eagle Pass, claiming among other violations in the lawsuit, that the installation had damaged diplomatic relations with Mexico.

Last week, The Border Chronicle requested access from DHS to fly a drone to film the installation from the US-side of the Rio Grande and was denied by the agency, which said it was placing “a media hold” on requests. The entire section of the river was placed under a National Defense Area designation, and military control in September 2025. The only way to document the U.S. government’s actions on the binational river was from Mexico. Several stories were published yesterday and today in the Mexican media about the installation of the barriers.

[Burning coffee sacks in Chiapas: Desperate farmers protest against Nestlé’s low purchase prices]

The nurse reportedly suggested medical providers carry syringes with an anesthetic in them to cause short-acting muscle paralysis in ICE agents. She also reportedly suggested putting poison ivy in a squirt gun to aim at ICE agents, among other things, she called “sabotage tactics.”

Common “Accidental” Scenarios

Accidental toxin production typically happens when people unknowingly create an “anaerobic” (oxygen-free) environment for low-acid foods:

- Improper Home Canning: Using a boiling water bath instead of a pressure canner for low-acid vegetables like green beans, asparagus, or potatoes.

- Infused Oils: Storing homemade garlic-in-oil or herb-infused oils at room temperature for more than a few days.

- Foil-Wrapped Potatoes: Leaving baked potatoes wrapped in aluminum foil at room temperature for several days; the foil creates an oxygen-free seal around the potato.

- Traditional Fermentation: Specific cultural practices involving fermented fish or marine mammal meat (common in Alaska).

My friend, Tassos, where I learned how to cook Greek food and where one of my marriages hosted a wedding dinner.

EL PASO, Texas, April 12, 1994 — Fourteen people who ate a garlic and potato-based dip at a Greek restaurant remained hospitalized Tuesday in what officials said may be the worst outbreak of botulism in Texas history.

The 14 were among 30 people who ate the dip at Tassos Greek Cuisine and Seafood Restaurant, said El Paso city-county Health and Environmental District director Dr. Laurance Nickey.

Four of the victims are in serious condition and breathing with the aid of ventilators, hospital officials said.

The outbreak was believed to involve more people than any single food-borne botulism episode in state history, said Dr. L. Bruce Elliott, director of microbiology services at the Texas Department of Health.

Food-borne botulism stems from toxins in food that is inadquately cooked or improperly stored. The undercooked foods become toxic after they are canned or placed in another type of oxygen-free environment.

Even though all the victims said they ate the dip, several other dishes served at the restaurant containing various ingredients are also being tested, Elliott said.

Bob Howard, a spokesman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, said ‘We would classify this as a major or unusual outbreak’ due to the unusually high number of victims.

The CDC sent a representative to El Paso to join local experts and Texas Department of Health experts in the investigation, officials said.

Skordalia, a dip consisting of potatoes, garlic, cucumbers and sometimes yogurt, was served Friday and Saturday at the restaurant, which voluntarily closed pending the completion of an investigation.

Symptoms of botulism include blurred or double vision, headache, difficulty swallowing or talking, fatigue and respiratory difficulty. The fatality rate is 10 to 20 percent, the CDC said.NEWLN: (Written by Dick Kelsey in Dallas; edited by Phil Magers in Dallas)

The nurse reportedly said her ideas were not meant to kill or seriously harm anyone, but she wanted to “make their lives miserable.”

+—+

Make a Homemade Stink Bomb

- A stink bomb is a device usually used as a practical joke that produces a highly unpleasant odor.

- Leonardo da Vinci invented a stink bomb that could be delivered to enemies using arrows.

- Most stink bombs contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Compounds that contain sulfur (such as thiols) are particularly effective.

Homemade Stink Bomb Ingredients

You’ll only need three materials for this project. The smell in the stink bomb comes from the reaction between the chemicals in the matches and the ammonia. While any container that can be sealed will work, a plastic bottle is recommended because it won’t break. However, another option is to use a plastic zip-top baggie.

- Book of matches (20 matches)

- Household ammonia

- A clean, empty 20-ounce plastic bottle with a cap

Making the Stink Bomb

- Use scissors or a knife to cut the heads off of a book of matches. Be careful not to cut yourself.

- Place the match heads inside the empty 20-ounce bottle. Add about 2 tablespoons of household ammonia.

- Seal the bottle and swirl the contents around.

- Wait three to four days before uncapping the bottle to give the chemical reaction enough time to take place. After 72 to 96 hours, your stink bomb will be ready.

- When you’re ready to release the stink, uncap the bottle.+—+

Jew Jabs, Jew Stink: It’s called Skunk, a type of “malodorant,” or in plainer language, a foul-smelling liquid. Technically nontoxic but incredibly disgusting, it has been described as a cross between “dead animal and human excrement.” Untreated, the smell lingers for weeks.

The Israeli Defense Forces developed Skunk in 2008 as a crowd-control weapon for use against Palestinians. Now Mistral, a company out of Bethesda, Md., says they are providing it to police departments in the United States.

[…]

The Israelis first used it in 2008 to disperse Palestinians protesting in the West Bank. A BBC video shows its first use in action, sprayed by a hose, a system that has come to be known as the “crap cannon.”

Mistral reps say Skunk, once deployed, can be “neutralized” with a special soap and only with that soap. In another BBC video, an IDF spokesman describes how any attempt to wash it via regular means only exacerbates its effects. Six weeks after IDF forces used it against Palestinians at a security barrier, it still lingered in the air.

Oh, so Defending the City: An Overview of Defensive Tactics from the Modern History of Urban Warfare

The urban environment offers a multitude of large objects that allow defending forces the ability to create obstacles both inside and outside of buildings. Vehicles can be repositioned to block streets, furniture can be thrown into staircases, and concertina wire and remotely detonated explosive devices can be added to hinder easy movement between floors and into entryways of buildings. Concrete barriers, cars, buses, construction vehicles, dumpsters, furniture, and tires can be moved into streets and flipped over to channel, divert, or halt enemy armored fighting vehicles or dismounted personnel.

Sorry, more house negroes:

At Georgetown, a senior administrator reported, “The freshmen are much more radical than the seniors, and I’m told the high school students coming up are even more so.” Though the underground paper The Berkeley Barb put it more colorfully: “Che Guevara is thirteen years old, and he is not doing his homework.”

Operational Counter-Tactics

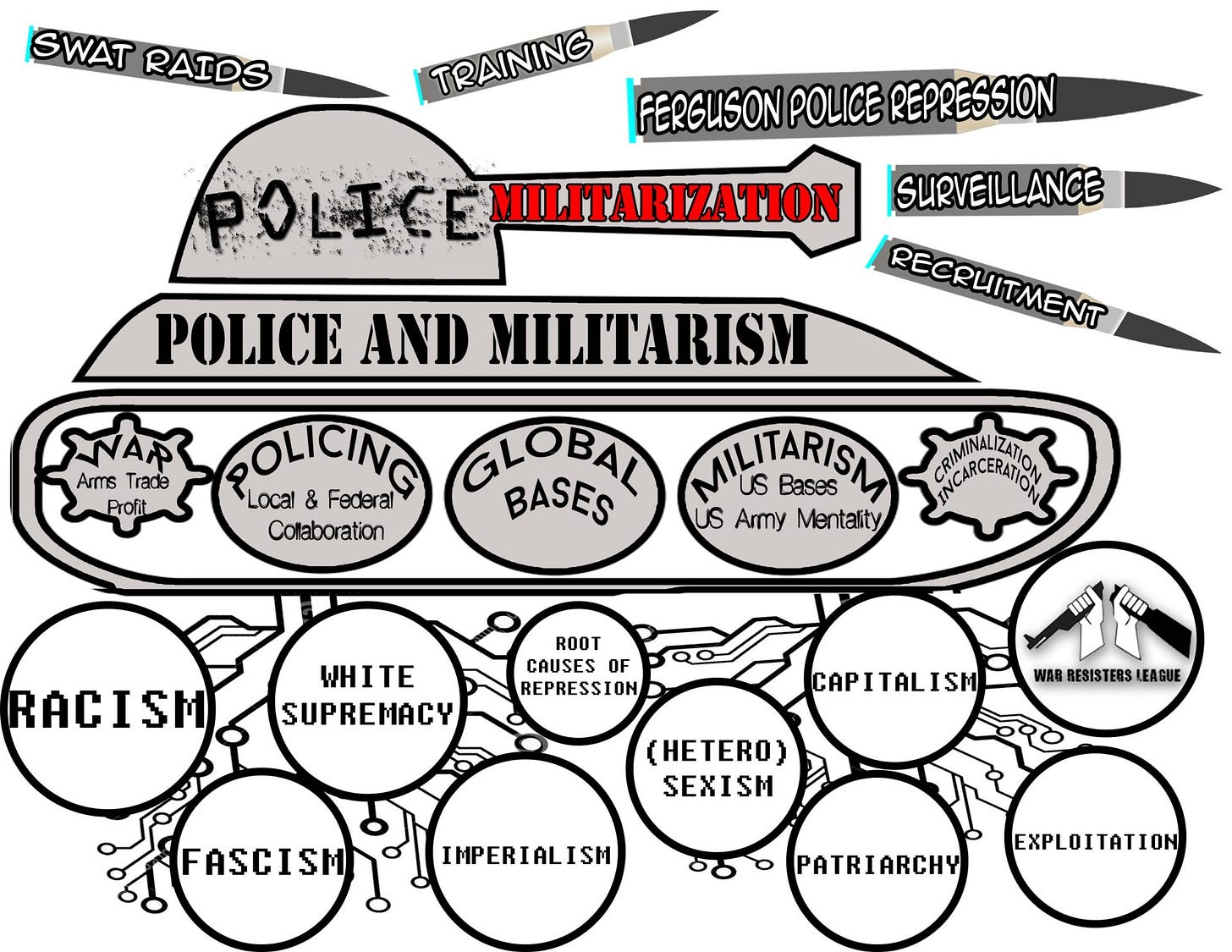

Tactics used to counter militarized police operations in urban areas include:

- Documentation and Monitoring: Utilizing cameras and apps to record police actions, especially concerning the deployment of armored vehicles, drones, and riot gear, to ensure accountability.

- Creating Safe Zones: Establishing community areas designated as safe from police intervention to foster community support and resilience.

- Recruiting Local Informants: Sociology Professor Julian Go notes that tactics similar to “search and destroy” used against indigenous populations in the 1800s, including surveillance and informant recruitment, have been adapted in modern urban policing.

- Utilizing Concrete Barriers: Existing concrete barriers in cities, such as those used for infrastructure protection, can serve as defensive fortifications. Steel-reinforced concrete is a significant obstacle, as demonstrated by the defense of Mosul.

- Fortifying Buildings: Reinforcing existing robust structures like government buildings or apartment complexes can create strongpoints. These fortified buildings act as mini-fortresses and can be further strengthened with materials and obstacles like sandbags, wire, and mines to hinder attackers. Historical examples, such as “Pavlov’s House” in the Battle of Stalingrad, show the effectiveness of using fortified buildings with good lines of sight and obstacles to hold off attacks.

- Creating Rubble Barriers: Intentionally destroying buildings or using existing rubble to block streets and create obstacles can channel attacking forces into disadvantageous areas and impede their movement and the use of supporting vehicles. German forces used this tactic extensively during the Battle of Ortona to restrict Canadian movement.

- Placing Heavy Weapons in Buildings: Positioning disassembled heavy weapons on higher floors of buildings provides superior firing angles and protection, creating formidable defensive positions. Examples include the Japanese using naval guns in Manila buildings and German forces using antitank guns in Ortona.

- Using Concealment: Simple materials like wood, tin, tarpaulins, or cloth sheets can be used to create cover from aerial surveillance, hiding obstacles and personnel in urban environments. This has been observed in cities like Aleppo.

+—+

You’re alive right now because of 90 seconds in 1962 when one man said “No”—and saved 7 billion people who hadn’t even been born yet.

October 27, 1962. Black Saturday. The day the world came within a heartbeat of ending.

Deep beneath the Caribbean, invisible to the world above, Soviet submarine B-59 had become a steel coffin. The air conditioning had failed days earlier. Internal temperature: 122°F. Men were collapsing from heatstroke, one after another, “falling like dominoes.” Carbon dioxide levels had reached the point where breathing felt like suffocation. The crew hadn’t heard from Moscow in nearly a week. For all they knew, World War III had already started.

Then the explosions began.

Eleven US Navy destroyers had surrounded their position. They started dropping depth charges directly overhead—practice charges meant as warning signals to force the submarine to surface. But the Soviets had no way of knowing that.

To the crew of B-59, trapped in darkness and unbearable heat, each blast sounded like death arriving. The metal hull screamed. Equipment shook loose. Vadim Orlov, a crew member, later described it: “It felt like you were sitting in a metal barrel, which somebody is constantly blasting with a sledgehammer.”

Captain Valentin Savitsky snapped.

Oxygen-deprived, heat-exhausted, convinced war had begun, he started screaming orders: “Maybe the war has already started up there, while we are doing somersaults here! We’re going to blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all—we will not disgrace our Navy!”

He ordered his crew to arm the Special Weapon.

A nuclear torpedo. Fifteen kilotons. Roughly the power of the Hiroshima bomb. Enough to vaporize the American fleet overhead instantly. And if that weapon launched, the United States would assume nuclear war had begun. Moscow would be struck within hours. The Soviets would retaliate. London. Paris. New York. Hundreds of millions dead in the first day. Billions more in the aftermath.

But there was a technicality. A bureaucratic detail that saved the world.

Soviet protocol required unanimous consent from all three senior officers aboard to launch a nuclear weapon. On other submarines, only two signatures were needed. But B-59 was the flagship. It had three command officers.

Captain Savitsky screamed his approval.

The Political Officer, Ivan Maslennikov, gave his.

Two votes for annihilation.

They turned to the third man.

Vasili Arkhipov. Age 34. Flotilla Commander. The man who had survived the K-19 submarine disaster a year earlier—a near-nuclear meltdown that killed eight crewmates and left him with radiation poisoning. The man who understood, perhaps better than anyone else aboard, what nuclear weapons actually did.

Every fiber of logic and instinct pointed toward yes. The explosions were real. The threat felt immediate. His captain was ordering him. His crew was watching. His country seemed under attack.

Arkhipov looked at the faces around him. He heard the explosions. He felt the crushing heat.

And then he said one word:

“No.”

His voice, impossibly calm in the chaos. “These are not attacks. These are signals. Warnings to surface. If we launch this weapon, we end the world. We cannot know if war has started. We must surface and confirm.”

Captain Savitsky exploded. A screaming match erupted in the suffocating control room. Officers argued. Men shouted. The pressure was crushing. Minutes felt like hours.

But Arkhipov would not move. He would not turn his key. He would not give his vote.

Without unanimous approval, the launch was impossible.

Gradually, impossibly, Arkhipov convinced Savitsky to reconsider. They would surface. They would make contact. They would find out the truth before ending civilization.

The submarine rose through the dark water and broke the surface. American destroyers surrounded them. Tense moments passed as searchlights blazed. One destroyer even had a jazz band playing on deck—a surreal detail that probably saved even more lives by easing the tension.

But there were no missiles. No attacks. No war.

B-59 was escorted away. The crew went home. The world continued turning, completely unaware of how close it had come to ending.

When B-59 returned to Soviet waters, they faced disgrace. They had been detected. Forced to surface by Americans. In the Soviet military hierarchy, this was failure. Arkhipov spent the rest of his career in obscurity. He never sought recognition. He died quietly in 1998 at age 72, from radiation exposure suffered during the K-19 accident.

The world had no idea what he had done.

Not until 2002—40 years later—when Soviet files were declassified and a conference was held in Havana. For the first time, the full story emerged. American officials sat in stunned silence as they learned how close they’d come. Former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara admitted: “We came very, very close to nuclear war, closer than we knew at the time.”

Thomas Blanton, director of the National Security Archive, spoke the words that would define Arkhipov’s legacy:

“The guy called Vasili Arkhipov saved the world.”

Think about that for a moment.

One man. One word. One decision made under unimaginable pressure, in unbearable heat, surrounded by chaos.

He didn’t save a city. He didn’t save a nation. He saved every person born after October 27, 1962. Every child who grew up in the 1970s, 80s, 90s, 2000s. Every baby born this year. Every dream realized. Every love story. Every scientific discovery. Every sunrise.

All of it exists because a man nobody had heard of chose reason over panic.

In 2017, the Future of Life Institute finally honored Arkhipov posthumously with the first Future of Life Award, presenting it to his daughter Elena and grandson Sergei. The award recognizes “exceptional measures, often performed despite personal risk and without obvious reward, to safeguard the collective future of humanity.”

Vasili Arkhipov proved something profound about human nature. That true courage isn’t about how quickly you can pull a trigger—it’s about the strength to keep your hand steady when everything around you is screaming for action. It’s about choosing reason when panic feels justified. It’s about understanding that some decisions are too important to make in rage.

Every breath you’ve ever taken. Every person you’ve ever loved. Every moment you’ve experienced. Every tomorrow you’ll wake up to.

All of it exists because on one suffocating afternoon in October 1962, beneath the turquoise waters of the Caribbean, a soft-spoken Soviet officer decided that humanity deserved one more chance.

Remember his name: Vasili Arkhipov.

The man who saved the world by saying no.

Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla

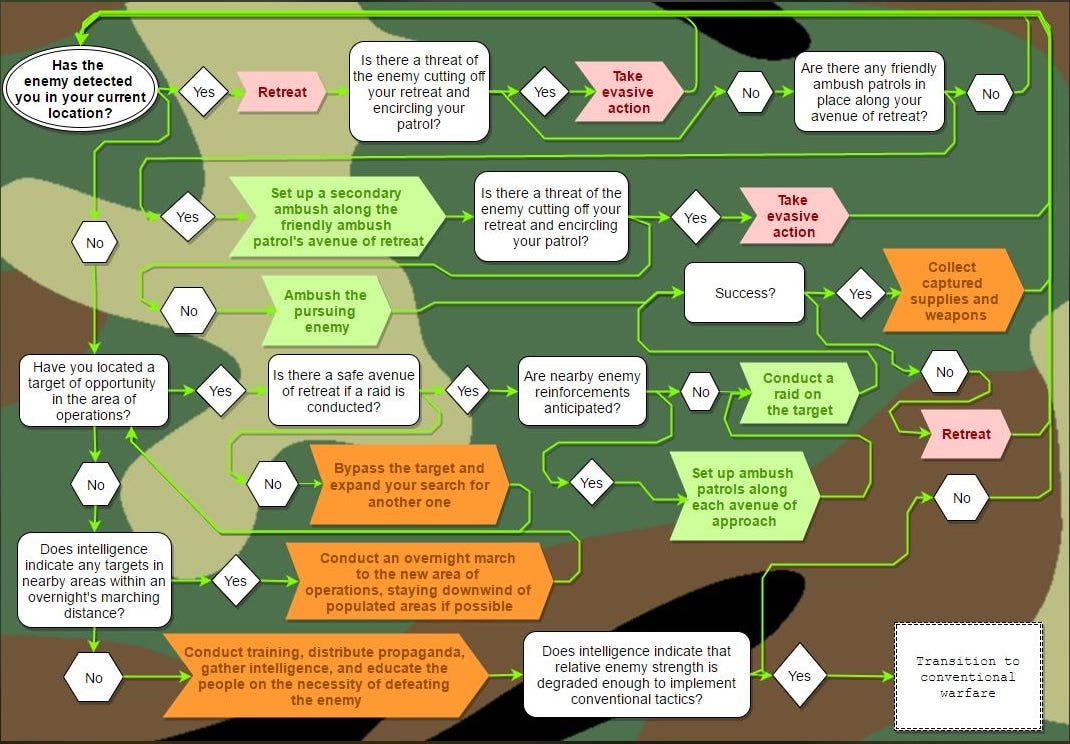

Street tactics are used to fight the enemy in the streets, utilizing the participation of the population against him.

In 1968, the Brazilian students used excellent street tactics against police troops, such as marching down streets against traffic and using slingshots and marbles against mounted police. Other street tactics consist of constructing barricades; pulling up paving blocks and hurling them at the police; throwing bottles, bricks, paperweights and other projectiles at the police from the top of office and apartment buildings; using buildings and other structures for escape, for hiding and for supporting surprise attacks. It is equally necessary to know how to respond to enemy tactics. When the police troops come wearing helmets to protect them against flying objects, we have to divide ourselves into two teams—one to attack the enemy from the front, the other to attack him in the rear—withdrawing one as the other goes into action to prevent the first from being struck by projectiles hurled by the second. By the same token, it is important to know how to respond to the police net. When the police designate certain of their men to go into the crowd and arrest a demonstrator, a larger group of urban guerrillas must surround the police group, disarming and beating them and at the same time allowing the prisoner to escape. This urban guerrilla operation is called “the net within a net”.

When the police net is formed at a school building, a factory, a place where demonstrators gather, or some other point, the urban guerrilla must not give up or allow himself to be taken by surprise. To make his net effective, the enemy is obliged to transport his troops in vehicles and special cars to occupy strategic points in the streets, in order to invade the building or chosen locale. The urban guerrilla, for his part, must never clear a building or an area and meet in it without first knowing its exits, the way to break an encirclement, the strategic points that the police must occupy, and the roads that inevitably lead into the net, and he must hold other strategic points from which to strike at the enemy. The roads followed by police vehicles must be mined at key points along the way and at forced roadblocks. When the mines explode, the vehicles will be knocked into the air. The police will be caught in the trap and will suffer losses and be victims of an ambush. The net must be broken by escape routes which are unknown to the police. The rigorous planning of a withdrawal is the best way to frustrate any encircling effort on the part of the enemy. When there is no possibility of an escape plan, the urban guerrilla must not hold meetings, gatherings or do anything, since to do so will prevent him from breaking through the net which the enemy will surely try to throw around him.

Street tactics have revealed a new type of urban guerrilla who participates in mass protests. This is the type we designate as the “urban guerrilla demonstrator”, who joins the crowds and participates in marches with specific and definate aims in mind. The urban guerrilla demonstrator must initiate the “net within the net”, ransacking government vehicles, official cars and police vehicles before turning them over or setting fire to them, to see if any of them have money or weapons.

Snipers are very good for mass demonstrations, and along with the urban guerrilla demonstrator can play a valuable role. Hidden at strategic points, the snipers have complete success using s

Does American law enforcement treat The Anarchist Cookbook as “contraband”? One definition of contraband is an item that is not permitted in prison. It seems that the book is generally not permitted in American prisons, judging by cases in which individual prisoners unsuccessfully litigated their right to possess the book in their cells. Another common definition of contraband is something that has been imported or exported illegally. If, as Grimm suggests, border officials can be expected to seize the book during searches, The Anarchist Cookbook might qualify.

It is not illegal for Americans who are not incarcerated to possess the book, nor to buy it or download it. It might not be “contraband” in this sense. However, if you are suspected of being involved in some crime involving guns or explosives or drugs, it is very dangerous to have a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook at your house or on your computer. If you do, it could well be seized by law enforcement and used against you in your criminal trial. In this sense, literate criminals are prosecuted in part for their particular reading habits, if those habits include this particular book.

Indeed, not a single American court opinion has taken issue with law enforcement’s seizure of The Anarchist Cookbook during a raid, even when judges are reluctant to ultimately admit the book into evidence. Courts have consistently blessed the practice of seizing this book during an investigation, almost as if The Anarchist Cookbook qualified as contraband.

Books as Contraband: The Strange Case of ‘The Anarchist Cookbook’ — Another shitty school and another shitty course: Jeff Breinholt is an adjunct professor at the George Washington University Law School, where he teaches a course on trying terrorists. The views in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.

New self-defense militia appears in Chiapas, Mexico to fight organized crime

“I won’t give you my name but put that I am Maniguas so that “El Chayo” sees where I am and how I will receive him when he comes looking for me,” this vigilante tells EL PAÍS.

Meet the armed vigilantes fighting for Michoacán

María de Jesús Patricio Martínez is surrounded by supporters after registering to run in the presidential elections

Mexico’s Zapatista rebels, 24 [31] years on and defiant in mountain strongholds

The peasant rebels took up arms in 1994, and now number 300,000 in centres with their own doctors, teachers and currency, but rarely answer questions – until now

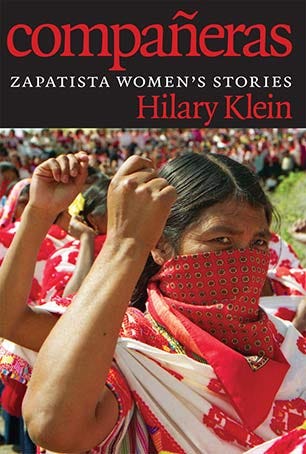

After centuries of oppression, a few indigenous voices of dissent in Chiapas, Mexico, rose up to became a force of thousands – the Zapatistas. Hilary Klein’s Compañeras relays the stories of the Zapatista women who have overcome hardship to strengthen their communities and build a movement with global influence. Click here to order your copy of this inspiring book today!

The following excerpt is from the introduction to Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories:

After visiting us several times, they began to explain the struggle: what they were fighting for and whom they were fighting against. They told us there was a word we could use to show our respect for each other, and that word was compañeros or compañeras. Saying it meant that we were going to struggle together for our freedom. —ARACELI and MARIBEL, Zapatista women from the La Realidad region

In the 1980s, outsiders dressed as doctors or teachers arrived in Araceli and Maribel’s jungle community and began asking the peasants why they were paid such low prices when they sold their coffee or corn. These outsiders talked about the fundamental injustices between rich and poor, and about the mistreatment their indigenous community had endured for more than five hundred years. They said that women had rights too. Villagers like Araceli and Maribel took a risk and joined “the organization.” They attended secret meetings at night and recruited their neighbors. Some left home to live in the mountains and become insurgents – joining a scrappy indigenous army that was growing in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas.

On January 1, 1994, the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation, EZLN) captured the world’s imagination when it rose up to demand justice and democracy – taking on the Mexican government and global capitalism itself. The EZLN is named after Emiliano Zapata, a hero of the Mexican Revolution, and it took up his rallying cry of tierra y libertad (land and freedom). From its formation in 1983 until the 1994 uprising, the EZLN was a clandestine organization. Since that brief armed insurrection, the EZLN has become known primarily for its peaceful mobilizations, dialogue with civil society, and structures of political, economic, and cultural autonomy. During the decade leading up to and the decade after the uprising, women from the indigenous Mayan villages that belong to the EZLN experienced dramatic transformations in their lives, their communities, and their level of political participation and leadership.

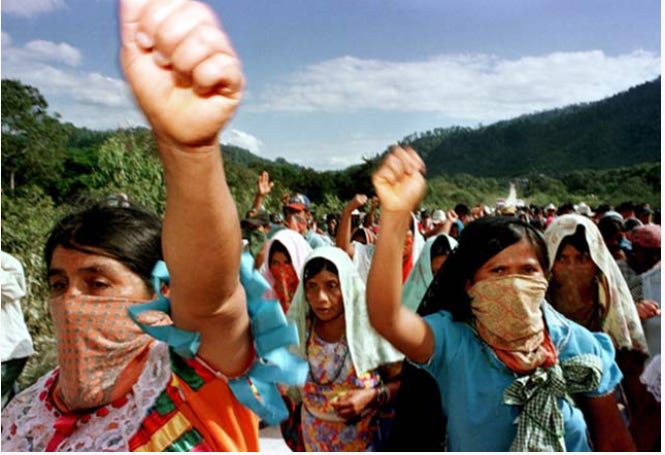

(Image: Seven Stories Press)People around the world have been inspired by images of Zapatista women: Major Ana María wearing a black ski mask and brown uniform, leading indigenous troops during the uprising; Comandanta Ramona standing next to Subcomandante Marcos during peace negotiations with the Mexican government, the top of her head barely reaching his shoulder; Comandanta Ester, draped in a white shawl with embroidered flowers, addressing the Mexican Congress to demand respect for indigenous rights and culture. The dignity with which these women carried themselves, set against a backdrop of centuries of racism and exploitation, embodies what the Zapatista movement has come to represent – the resistance of the marginalized and the forgotten against the powerful. Peasants turned warriors, mothers turned revolutionary leaders – dozens, hundreds, thousands of Zapatista women gather, tiny and dark-skinned, with red bandannas covering their faces and masking their individual identities, long black braids hanging down their backs, their fists in the air. They have marched, they have organized, and they have planted seeds – both real and symbolic. They have stood up to the Mexican army and to their own husbands. They have changed their own lives and they have changed the world around them.

From the civil rights movement in the United States to the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, from the campaign against apartheid in South Africa to the Arab Spring uprisings in the Middle East, women have fought side by side with men for their people’s freedom. Women have been important actors and made invaluable contributions to grassroots social movements and national liberation struggles all over the world. Many of these, while not women’s movements per se, have created new opportunities for women and catalyzed changes in their lives. At the same time, women almost invariably face discrimination within their own organizations, and have often had to fight for women’s rights to be included in the vision of a just society. This dual and interdependent relationship between women’s liberation and social revolution illustrates that popular struggles cannot achieve collective liberation for all people without addressing patriarchy and, likewise, women’s freedom cannot be disentangled from racial, economic, and social justice.

The indigenous communities that make up the EZLN have historically confronted extreme inequality: economic, because of the legacy of colonialism and the concentration of land and wealth in Chiapas; political, because of their exclusion from state, national, and local decision making; and social, because of racism against indigenous people and the lack of basic services such as health care, education, electricity, and potable water. Women have also faced gender-based discrimination. In the words of Comandanta Ester, from a speech she gave in Mexico City’s central plaza in 2001, “We are oppressed three times over, because we are poor, because we are indigenous, and because we are women.” This history of marginalization serves as a backdrop for the striking changes that have taken place in Zapatista territory.

Today, the Zapatista movement has a presence throughout eastern Chiapas, with most of the EZLN’s support base living in rural indigenous villages. The Zapatista support base refers to the civilians – individuals and communities – who belong to the EZLN. The Mexican newspaper El Universal reports the Zapatista support base to be approximately 250,000 people, representing about 22 percent of the indigenous population of Chiapas.

Zapatista territory is not “liberated territory” in the traditional sense that a guerrilla army has complete control over a certain area. The Mexican military has an intense presence throughout the region, and within Zapatista territory there are Zapatista and non-Zapatista villages, and some that are divided between the two. There are clear boundaries of Zapatista territory, however, and this is meaningful because in this small corner of the world, the Zapatistas are experimenting with self-government that functions independently from the existing state and federal system, alternative education and health care infrastructure, and an economic system based on cooperation, solidarity, and relationships of equality.

A small Zapatista village might have a dozen families, whereas larger villages have a hundred families or more. Zapatista communities are organized into autonomous municipalities, which function as something like counties. Each autonomous municipality is made up of anywhere from a dozen to a hundred villages. The EZLN has drawn its own geographical lines, corresponding to where its support base resides and often defined by geography: all the villages along a particular canyon, for example.

The EZLN’s approximately forty autonomous municipalities are organized into five regions, which the Zapatistas call “zones.” Each region or zone is commonly referred to by the name of the five villages that house the Caracoles (previously called Aguascalientes), the seat of each regional autonomous government. Morelia, La Garrucha, and La Realidad are in the canyons that run eastward to the Lacandon Jungle, and correspond roughly to the official municipalities of Altamirano, Ocosingo, and Las Margaritas, respectively. Oventic is in the central highlands of Chiapas, near the colonial city of San Cristóbal de las Casas, and Roberto Barrios is in the northern zone, near the Mayan ruins of Palenque.

January 2014 marked the twentieth anniversary of the Zapatista uprising and thirty years since the EZLN’s formation as an underground organization. Over the past three decades, the impact of the Zapatista movement can be seen at the local, national, and international level. Land takeovers carried out after the 1994 uprising – where large ranches were occupied by the Zapatistas and reapportioned to landless peasants – impacted the distribution of wealth in eastern Chiapas and continue to affect living conditions for those Zapatista communities farming on reclaimed land. Most Zapatista villages are still poor, but have experienced some concrete material improvements. The Zapatista construction of indigenous autonomy has meant that rural villages in Chiapas have gained access to rudimentary health care and education, which they were previously denied. They exercise self-determination through autonomous village and regional governments, and generate resources back into their communities through economic cooperatives that organize the production of goods.

At the national level, the EZLN signed the San Andrés Accords with the Mexican government in 1996, which recognized indigenous rights and promised indigenous autonomy. The Zapatista movement arguably helped bring an end to seventy years of one-party rule in Mexico when the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI), which had monopolized state power since the Mexican Revolution, lost the presidential elections in 2000. And, through its national mobilizations and dialogue with other sectors of the population, the EZLN is also credited with the strengthening of Mexican civil society.

Around the world, the Zapatistas catalyzed a wave of solidarity that inspired a generation of young activists to organize for social justice in their own contexts. The repercussions of the Zapatista movement at the international level may be difficult to measure, but should not be underestimated. International gatherings organized by the EZLN fostered the burgeoning global justice movement. Events inspired or influenced by the Zapatistas include the World Social Forum, an annual global forum for grassroots activists and organizations, and demonstrations against global capitalism, such as the protests in Seattle in 1999 against the World Trade Organization. Evo Morales, a Socialist and the first indigenous president of Bolivia, has often referred to the Zapatistas in his speeches and writings. Antiwar activists in San Francisco, trying to stop the second Gulf War in 2003, cited the Zapatistas as an inspiration. With its ideological critique of neoliberalism and its internal emphasis on participatory democracy, the EZLN was also a precursor to the Occupy and “We Are the 99 Percent” movements that emerged almost two decades after the Zapatista uprising. Perhaps most importantly, the EZLN offered one answer to the question of what the next wave of liberation struggles might look like after the end of the Cold War.

While the EZLN is rightfully known for these contributions, there is another, often less celebrated piece of the story. Women’s leadership within the organization is one of the most compelling aspects of the Zapatista movement. Zapatista women have served as insurgents, political leaders, healers, educators, and key agents in autonomous economic development. Women’s participation in the EZLN has helped shape the Zapatista movement which has, in turn, opened new spaces for women and led to dramatic changes in their lives. A woman who was abused as a teenager at the hands of a husband chosen by her father would later join a caravan of thousands of Zapatistas marching on Mexico City to demand indigenous rights. Along the way, she would meet with other Mexican women and urge them to fight for their liberation as she had. Compañeras documents these changes through the voices of women who lived them.

Copyright (2015) by Hilary Klein. Not to be reprinted without permission of the publisher, Seven Stories Press.