“Revolution is born as a social entity within the oppressor society.” —Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Jan 29, 2026

The dichotomy between the social worker as a nine-to-five state agent and five-nine activist is a crucial one. The question can be summarised as: is there space, willingness and scope within social work to engage with broader structural issues that affect the lives of the people we work with?

I spent an hour with the Revolutionary Social Worker, who has a couple of Podcasts.

The radio broadcast comes to Lincoln County and Internet listeners on March 4, 6 PM, Pacific, over at KYAQ.org, 91.7 FM, my show, Finding Fringe. Listen to it. What follows below is me riffing with the subject matter, not a transcript of the interview, which is worth it’s weight in gold.

Christian Ace Stettler is a professor, podcaster, father, and founder of Revolutionary Social Work. My work is rooted in the belief that meaningful social transformation begins with personal transformation. I teach, speak, and write at the intersection of critical pedagogy, Indigenous knowledge, trauma healing, and social work practice.

I currently teach at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and co-host two podcasts: The Critical Social Worker and The Revolutionary Social Work Podcast, where I facilitate deep dialogue with guests from around the world exploring healing, justice, and becoming more fully human.

I also lead dialogic talking circles rooted in relational accountability, critical reflection, and kinship. These circles are not only a pedagogical tool but a personal and communal practice for liberation.

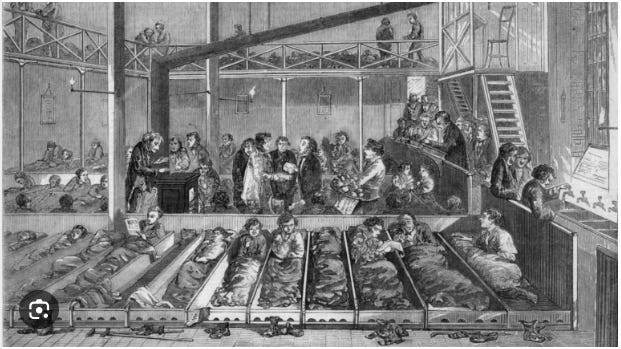

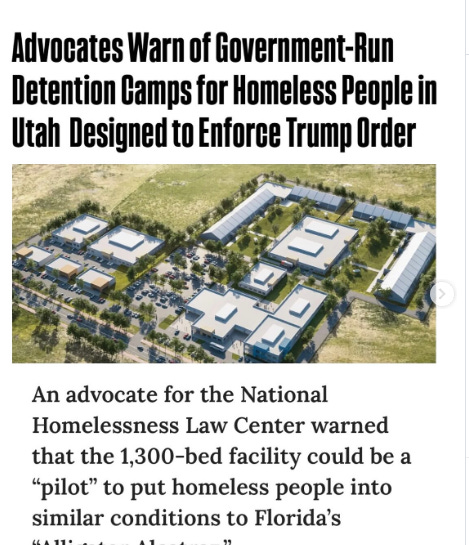

We are still in Dickensian times: Claims of the Charity Organisation Society, which in the 19th century insisted on portraying poverty as an issue exclusively linked to people’s feeble and manipulative personalities. [Sounds like EVERY single fucking one of the Semen Drip Brownshirt Trump’s Gang of Ghouls.]

This quote below is antithetical to the Trump Bigotry and Racism Doctrine as well at the Republican Party’s 50 Years of Hate ethos.

Now?

The idea of a settlement—as a colony of learning and fellowship in the industrial slums—was first conceived in the 1860s by a group of prominent British reformers that included John Ruskin, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley, and the so-called Christian Socialists, They were idealistic, middle-class intellectuals, appalled at the conditions of the working classes, and infused with the optimism, moral fervor; and anti-materialist impulses of the Romantic Age: people who read the soaring poetry of Wordsworth and Tennyson, the conscientious novels of Dickens, the liberal political thought of the Utilitarian philosophers Bentham and Mill. They were alarmed by a number of aspects of industrial capitalism: the growing gulf between the classes; the materialist ethos of the Industrial Revolution, and the emphasis on self-interest in classical economics; the terrible poverty of the average factory worker, and the brutal routinization of work, as the factory system replaced the individual craftsperson.

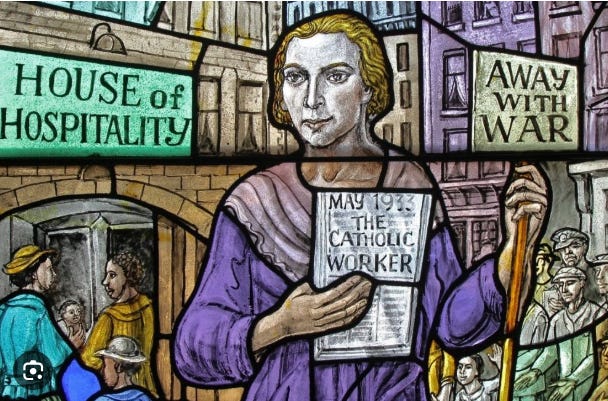

Jane Addams was a famous activist, social worker, author, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, and she is best known for founding the Hull House in Chicago, IL. Hull House was a progressive social settlement aimed at reducing poverty by providing social services and education to working-class immigrants and laborers (Harvard University Library, n.d.).

Jane Addams was born in Cedarville, IL in 1860, and she graduated from Rockford College in 1882. In 1888, while traveling in London, Addams visited the settlement house Toynbee Hall (Harvard University Library, n.d.). Her experiences at Toynbee Hall inspired her to recreate the social services model in Chicago. In 1889, she leased a large home built by Charles Hull, which she chose for its “diversity and variety of activity for which it presented an opportunity.” In her essay, “The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements,” Addams stated that the settlement movement existed to add social function to political democracy, to assist the progress of humanity, and to express Christianity through humanitarian action (Tims, 1961).

Thus, with Hull House, Addams proposed to “provide a center for a higher civic and social life, to institute and maintain educational and philanthropic enterprises, and to investigate and improve the conditions in the industrial districts in Chicago” (Harvard University Library, n.d.). Addams sought to foster a place where social progress, education, democracy, ethics, art, religion, peace, and happiness could all be daily experiences (Tims, 1961). Hull House offered kindergarten and day care for children of working mothers, an art gallery, libraries, music and art classes, and an employment bureau. By its second year of operation, Hull House served more than 2,000 residents weekly. By 1900, Hull House expanded to include a book bindery, gym, pool, cooperative for working women, theater, labor museum, and meeting space for trade unions (Harvard University Library, n.d.).

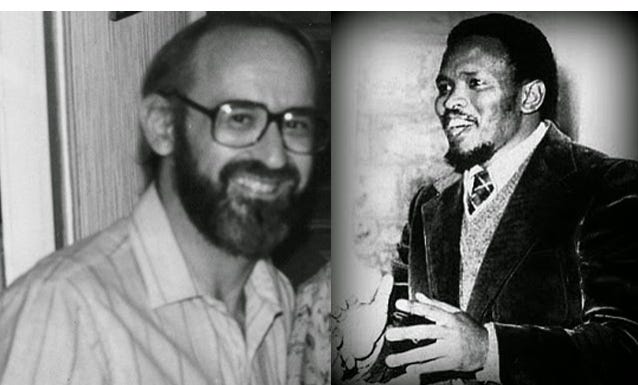

Martín-Baró argued that by considering psychological problems as primarily individual, “psychology has often contributed to obscuring the relationship between personal estrangement and social oppression, presenting the pathology of persons as if it were something removed from history and society, and behavioral disorders as if they played themselves out entirely in the individual plane” (p. 27). Instead, liberation psychology should illuminate the links between an individual’s psychological suffering and well-being and the social, economic, political, and ecological contexts in which he or she lives. At Pacifica we work to widen the original focus of liberation psychology to include the ecological, and thus we speak of eco-liberation psychology and practices, in our Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology, Indigenous Psychology, and Ecopsychology.

While liberation psychology is most strongly established in Latin America, Martín-Baró’s work has become a rallying call to psychologists and cultural workers on all continents to place into conversation their theories and liberatory practices.

Liberation Psychology Resources

- Liberation Psychology Network

- Liberation Theology

- Liberation Psychologies: An Invitation to Dialogue

- Liberation Psychology Bibliography

16 November marks the 37th anniversary of the killing of Ignacio Martín-Baró, the founder of Liberation Psychology in Latin America, along with 5 other priest-academics and two women workers by the Salvadorean army at their residence on the campus of the Unversidad de Centroamérica, San Salvador. It is fitting that today we bring you a typically beautifully written piece by Mohamed Seedat, in which he draws parallels between the work of Martín-Baró and Steve Biko, prominent leader in the Black Consciousness movement in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

New radicalism in social work has been based on five main pillars: democracy, empathy, militancy, anti-oppressiveness and structural practice. These pillars form the acronym Demos, a powerful concept which refers to “the populace of a democracy as a political unit”. Contrary to dominant social work narratives which claim that social workers’ legitimacy stems from their identity as creatures of the statute, radical social work has earned its recognition through an ability to grasp and utilise the transformative political power of the people we work with.

Ace:

Many of my core values as a human being and person are centered around family. I involve my wife and children in everything I do. We never go anywhere alone. For example, if I am invited to a conference to speak, I bring along one of my little apprentices (my children) and we often go as a family. I work with Alicia (my wife) on all of my creative projects and my children are often co-facilitators of my talking circles.

My writing, speaking, and teaching are grounded in Revolutionary Social Work values:

Kinning | Challenge the Status Quo | Non-Partisan Commitment | Relational Grounding | Indigenous and African-Centered Wisdoms | Transformative Reflection | (Re)Connection | Love as Praxis | Unity | Social Work Beyond the Profession

The revolution must begin with ourselves. I’m committed to an education and practice that centers humanity, story, presence, and place.

I got turned onto Ace’s work while doing some research on Tiokasin Ghosthorse:

My interview with the Lakota elder: Language of Domination — First Contact and Tiokasin Ghosthorse’s Intuitive Language

Ace and I covered a lot of territory, and we set down the foundation of genocide and the lack of response from his own brethren as a death by 200,000 dead Palestinian cuts.

Two years ago, Truthout: In a recent column for The New York Times, Pamela Paul described a shift in Columbia University’s School of Social Work toward a “radicalized” social justice framework. The piece has unearthed significant tensions within and outside the social work community, sparking heated debate about the role of social justice and a response decrying the so-called deterioration of social work.

What both pieces fail to recognize is the reality of social work’s historical and ongoing complicity in oppression and, to borrow a phrase from Martin Luther King Jr., “the fierce urgency of now,” especially during a genocide. Social work students like myself are organizing for a free Palestine in response to Israel’s genocide in Gaza. As we watch on-the-ground reporting from Palestinians sharing images and videos of their now-destroyed homes as they pull dead loved ones out from under the rubble, our profession fails to mobilize. This inaction reflects the failure of our leading social work institutions — most notably the National Association of Social Workers and the Council on Social Work Education — and of individual social workers who remain silent.

If our calling as social workers is to help those in need, we must support the 2.2 million Palestinians struggling to survive as the Israeli state relentlessly starves, bombs and displaces them before our very eyes. It is too late to help the tens of thousands of men, women and children killed by Israeli forces since October 7. But it is not too late for social workers to stand in solidarity with Palestine.

+—+

Dear National Association of Social Workers,

The situation in Palestine and Israel is top of mind for many people right now, especially your Jewish, Muslim, Palestinian, and Arab members, and many other fellow social workers.

We, the undersigned, are writing to express our deep disappointment regarding the recent statements made by the NASW[1] concerning the recent violence between Israel and Gaza.

We are social workers. Our profession is rooted in social justice[2], identifying oppression, and being courageous on behalf of the vulnerable. That’s why NASW released its Antiracism Statement[3] – not because it was easy, but because it was and is right. That’s why we center the dignity and worth of our clients[4] in the work that we do.

Today we need to find our courage again: to hold empathy for those who have lost their lives no matter which country or ethnicity they are part of, while also holding accountable those who are acting oppressively. Policies of supremacy and apartheid have and always will harm the oppressed, disadvantaged groups and those they claim to advantage. They separate us from the dignity and worth of every human and prevent us from building a better future.

When our profession is silent in the face of documented human rights violations and what Amnesty International has labeled apartheid[5], it calls into question our commitment to our stated values both on the international stage and among refugee, immigrant, Muslim, Arab, and other communities of color living in the United States. It also alienates our colleagues who hail from these groups and perpetuates the idea that social work as a profession is not inclusive of communities of color.

We call on all social work organizations to call for Israel to uphold international law by stopping the genocide of Palestinians and collective punishment of Gazans, and to call for immediate cessation of the siege and destruction of Gaza.

We call on all individual social workers to learn about the antecedents of the current wave of violence[6], the international law on this issue[7], and the growing violations of international law[8], as documented by Human Rights Watch. Culturally sensitive care is critical, and for those of you who work directly with refugee, immigrant, and diaspora communities who are impacted more directly by the ongoing violence, please take the time to read more deeply. Haymarket books has provided some options for your edification: https://www.haymarketbooks.org/blogs/495-free-ebooks-for-a-free-palestine and https://www.haymarketbooks.org/books/subjects/33-palestine

+—+

My own work in social services, working with Central American refugees in El Paso, as a case manager for foster youth/ homeless veterans/ just released inmates/ substance abuse citizens, employment specialist and direct support professional for adults with developmental disabilities, as well as being a teacher at community colleges and universities, well well, I have five PhDs worth of on-the-ground experience.

Most social workers at the county or state or VA level are not deep thinkers, never deeply critical of capitalism, and certainly are tied into the punishment and tokenism and redemption formula plied hard in this society.

Some of you read about just one of many issues I have had with retrograde non-profits sacking me: Falling into the Planned Parenthood Gardasil Snake Pit

+—+

Defund the Police/ Defund the Criminal Incarceration For-profit system.

Abolitionist social work is a theoretical framework and political project within the field of social work and an extension of the project of carceral abolitionism more broadly. Abolitionists seek to abolish punishment, prisons, police, and other carceral systems because they view these as being inherently destructive systems. Abolitionists argue that these carceral systems cause physiological, cognitive, economic, and political harms for incarcerated people, their families, and their communities; reinforce White supremacy; disproportionately burden the poor and marginalized; and fail to produce justice and healing after social harms have occurred. In their place, abolitionists want to create material conditions, institutions, and forms of community that facilitate emancipation and human flourishing and consequently render prisons, police, and other carceral systems obsolete. Abolitionist social workers advance this project in multiple ways, including critiquing the ways that social work and social workers are complicit in supporting or reinforcing carceral systems, challenging the expansion of carceral systems and carceral logics into social service domains, dismantling punitive and carceral institutions and methods of responding to social harms, implementing nonpunitive and noncarceral institutions and methods of responding to social harms, and strengthening the ability of communities to design and implement their own responses to social conflict and harm in the place of carceral institutions. As a theoretical framework, abolitionist social work draws from and extends the work of other critical frameworks and discourses, including anticarceral social work, feminist social work, dis/ability critical race studies, and transformative justice.

+—+

The Salvation Army’s Special Brand of Poverty Pimping

+—+

Have a listen to the interview.

Free PDF:

forward . . . partial: Paulo Freire’s invigorating critique of the dominant banking model of education leads to his democratic proposals of problem-posing education where “men and women develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality but as a reality in the process of transformation.” This offered to me—and all of those who experience subordination through an imposed assimilation policy—a path through which we come to understand what it means to come to cultural voice. It is a process that always involves pain and hope; a process through which, as forced cultural jugglers, we can come to subjectivity, transcending our object position in a society that hosts us yet is alien.

It is not surprising that my friends back in Cape Verde—and, for that matter in most totalitarian states—risked cruel punishment, including imprisonment, if they were caught reading Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I remember meeting a South African student in Boston who told me that students would photocopy chapters of Pedagogy of the Oppressed and share them with their classmates and peers. Sometimes, given the long list of students waiting to read Freire, they would have to wait for weeks before they were able to get their hands on a photocopied chapter. These students, and students like them in Central America, South America, Tanzania, Chile, Guinea-Bissau and other nations struggling to overthrow totalitarianism and oppression, passionately embraced Freire and his proposals for liberation. It is no wonder that his success in teaching Brazilian peasants how to read landed him in prison and led to a subsequent long and painful exile.

Oppressed people all over the world identified with Paulo Freire’s denunciation of the oppressive conditions that were choking millions of poor people, including a large number of middle-class families that had bitterly begun to experience the inhumanity of hunger in a potentially very rich and fertile country. Freire’s denunciation of oppression was not merely the intellectual exercise that we often find among many facile liberals and pseudocritical educators. His intellectual brilliance and courage in denouncing the structures of oppression were rooted in a very real and material experience, as he recounts in Letters to Cristina:

It was a real and concrete hunger that had no specific date of departure. Even though it never reached the rigor of the hunger experienced by some people I know, it was not the hunger experienced by those who undergo a tonsil operation or are dieting. On the contrary, our hunger was of the type that arrives unannounced and unauthorized, making itself at home without an end in sight. A hunger that, if it was not softened as ours was, would take over our bodies, molding them into angular shapes. Legs, arms, and fingers become skinny. Eye sockets become deeper, making the eyes almost disappear. Many of our classmates experienced this hunger and today it continues to afflict millions of Brazilians who die of its violence every year .