“Gray is for funerals.”… shit-stained AmeriKKKa, lost in the wilderness of wanton destroyers and fucking Trumpies and King Semen Drip Backed by Chosen Cultists and their half-shekel payola!

Dec 16, 2025

Well, half shekel times, hmm, times ten or a hundred billion bucks?

The current value of the biblical half shekel is $10.00. All half shekel donations made to the Temple Institute will go toward the physical, spiritual and educational preparations necessary for the rebuilding of the Holy Temple!

Something VERY wrong with this Anglocized image of Jews above!

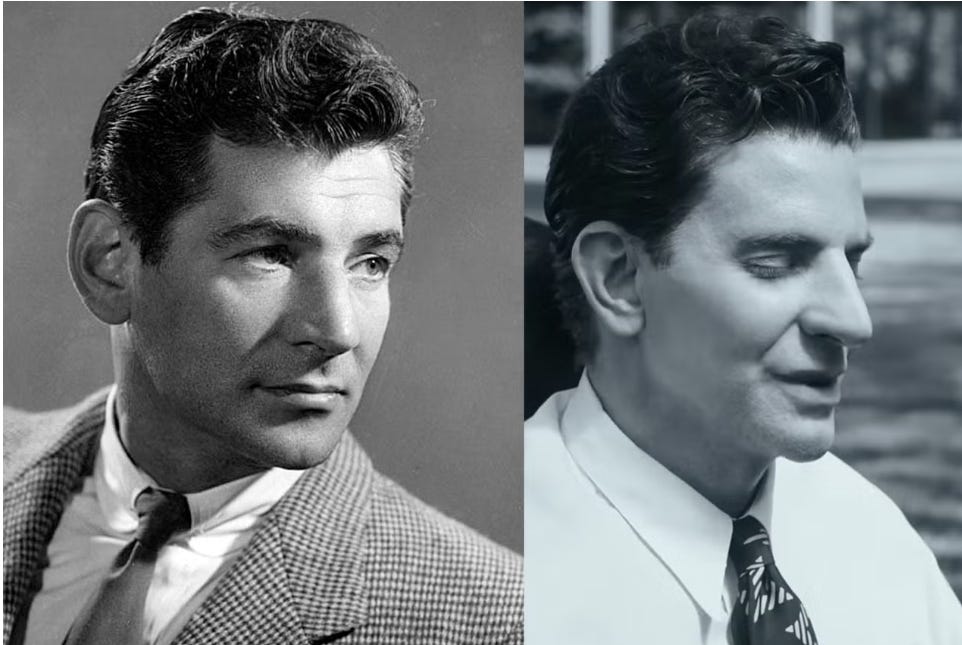

[Leonard Bernstein, left, and Bradley Cooper as Bernstein in Maestro, right.]

In 1914, a young woman who had always been self-conscious about the appearance of her nose decided to seek the advice of a surgeon. Her physician, Jerome Webster, made the following diagnosis: “Nose is fairly long, has a very slight hump, is somewhat broad near the tip and the tip bends down, giving somewhat the appearance of a Jewish nose.” Echoing the perspective of a generation of surgeons, Webster concluded, “I think that there is sufficient deformity to warrant changing the nose.”1

For over a century, the term the “Jewish nose” has been used in Western scientific literature to describe a set of physical features thought to constitute a distinct, race-based deformity. As early as 1850, Robert Knox, a prominent anthropologist, described the physical features of the Jew as including “a large, massive, club-shaped, hooked nose, three or four times larger than suits the face. . . . Thus it is that the Jewish face never can [be], and never is, perfectly beautiful.”2 In the 1900s, the “Jew nose” became the subject of purportedly scientific studies of hereditary transmission; a 1928 text described a “Jew nose” that emerged in the offspring of mixed Jewish and non-Jewish marriages, for example.3

By the early 20th century, physicians were arguing that surgical procedures to alter “racial characteristics” such as the “Jewish nose” could be a means of promoting patient well-being. In 1930, William Wesley Carter noted that “the modification of accentuated family or racial characteristics, such as are sometimes observable especially in Semitic subjects . . . is frequently of great importance to the individual.”4 Another surgeon, Vilray Blair, argued in 1936 that, due to prejudice against Jews, “change in the shape of the pronounced Jewish nose may be sought for either social or business reasons.”

[The Politics of “Jewface”

Sarah Silverman has come out against the casting of non-Jews in Jewish roles—a stance with a fraught racial history bound up with the legacy of blackface.]

The Long History of Jewface: Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic nose is the latest example of the struggles around Jewish representation on the stage and screen.

(Today’s discovery: Remember John Forsythe, the actor who played Dynasty’s Blake Carrington during the Reagan ’80s? Jewish! He was born Jacob Freund.) It’s something of a running joke that Jews and Italians are interchangeable on casting lists; they didn’t complain when James Caan played Sonny Corleone in The Godfather, and we didn’t complain when Al Pacino played Roy Cohn in Angels in America because, overall, we had sort of gotten to a place of comfort with some degree of interchangeability, from Daniel Radcliffe (Jewish) taking on “Weird Al” Yankovic (not) to …

Finishing that sentence is a problem, because non-Jews playing Jews is suddenly, for some, not OK. I’ll concede that some current examples, on paper, make me giggle. (Helen Mirren as Golda Meir? I mean, we’ll see, but let’s at least note that nobody howled about it much decades ago when Ingrid Bergman played the same role, even when makeup artists “buil[t] up her nose.”) But, perhaps since I don’t really care what an actor’s religious practice is, most examples of cross-religious casting elicit nothing more from me than a shrug. Cillian Murphy, a breakthrough star as J. Robert Oppenheimer, is not Jewish; he’s also not American. It didn’t matter—and it shouldn’t—because his talent and commitment to the title role in Oppenheimer speaks eloquently for itself. But the voices of those who object to this casting are getting louder. Kathryn Hahn (not Jewish! See, I warned you it’s hard to tell!) was recently warned away from playing Joan Rivers. And last year, The Fabelmans was briefly sideswiped for the casting of Michelle Williams and Paul Dano as Steven Spielberg’s parents. (Full disclosure: That movie was co-produced and co-written by my husband—a Jew who would probably best be played by John Turturro—and also co-produced by two of Maestro’s producers.) They were spared a full-blown controversy primarily because of the persuasive defense that Spielberg was probably better suited to select actors to play his own mother and father than @FilmTroll519485 was, and also because, last fall, The Whale’s Brendan Fraser was there to absorb all of the internet’s how-dare-he-play-this-part fury. (Reader, he won the Oscar.)

In terms of today’s money, what would be the value of the biblical half shekel?

Maimonides writes (Laws of Shekalim 1:5) that the half shekel mentioned in the Torah – the annual contribution every Jew was required to give to the Temple coffers – is equal to 160 grains of barley, which, in modern measurements, would be approximately eight grams of silver.

It is impossible to know silver’s value in biblical times. At today’s rate of approximately 17 US dollars per ounce, 8 grams of silver is around five dollars.1

Rabbi Eliezer Posner

Mark that $50 billion sent to Is-Raw-Hell from the American coffers.

Jews: An investment firm linked to Jared Kushner has abandoned a planned redevelopment in Belgrade. The decision follows protests, legal action, and growing anger over the removal of heritage status for the former army site.

Jew lawyers: The massive ballroom would dwarf those alterations. Images of heavy machinery tearing into the White House’s 120-year-old East Wing to make way for the project ignited condemnation, as critics accused Trump of abusing presidential power.

“No president is legally allowed to tear down portions of the White House without any review whatsoever — not President Trump, not President Biden, and not anyone else,” the National Trust’s lawsuit said.

Cuntology on both sides of the shit pile — dems and repubics.

The United States is currently in the midst of an affordability crisis, perched on the precipice of armed conflict or outright war with Venezuela, and attempting to revamp its entire immigration system and ward off shocking human rights violations against immigrants … in the midst of the country’s biggest measles outbreak in 33 years. It is safe to say that there are a few things on the plate of the President of the United States, in terms of crises that could use a little immediate attention from the executive branch. And so naturally, Donald Trump’s priority is taking near immediate federal control of … Washington D.C.’s public golf courses.

That’s according to Trump himself, speaking to The Wall Street Journal, noting that the federal government is moving to take over operations—a decidedly hostile takeover, it becomes clear—at all three of D.C.’s public, municipal golf courses: East Potomac, Rock Creek and Langston Golf Course. Those courses are currently managed by National Links Trust, a nonprofit formed in 2020 and given a 50-year-lease with the National Park Service—by the first Trump administration, mind you—to renovate the courses and provide accessible, affordable public golf to the D.C. area. Since that time, National Links Trust has been fundraising and jumping through legal hoops/permitting as it completes minor projects, with more serious renovation having recently begun at Rock Creek, which closed for construction in November. The organization has brought on well-known golf course architects like Gil Hanse, Tom Doak and Beau Welling to aid in the effort, offering pro bono services. But now, the Trump administration’s Interior Department is claiming that the National Links Trust is in fact in violation of its lease, issuing a formal notice of default and saying that the federal government will seize the courses to conduct its own renovations, whatever they may be. Trump’s own interest is reportedly central to the effort, and he told WSJ as much, saying that he didn’t want to work with National Links Trust despite his admin having awarded them a 50-year lease: “I think what we’re looking to do is just build something different, and build them in government. If we do them, we’ll do it really beautifully.”

Fucking BrokeBack Mountain, Daft Guy (Semen Drip Trump) Trying to be the Queer Guy for the Straight Guys!!

The 79-year-old Republican has brought a constant stream of changes to the White House property since returning to office in January 2025.

While recently speaking to Fox News’ Laura Ingraham, Trump hinted that his next idea involves a prominent building on the outskirts of the White House complex: the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, a massive National Historic Landmark that houses various agencies under the president’s purview.

In a “Seen and Unseen” segment on Wednesday, Nov. 12, Ingraham shared additional footage from her two-part interview with the president for her show, The Ingraham Angle.

While outside the White House getting a tour, Ingraham asked the Trump if the towering EEOB was going to get a paint job, saying, “I’ve heard rumor of that.”

“I may… I’ll show you a picture of it before and after, and you’ll make a determination,” Trump replied.

He showed a rendering to Ingraham, who once worked in the building during the Reagan administration, which depicted the EEOB painted stark white.

Did you get the memo yet? Bedlam and Cuckoo’s Nest a la Charles Dickens! One motherfucking chemical out of thousands, man, and the synergistic effects? Never ever will be tested.

Thousands of U.S. farmers have Parkinson’s. They blame a deadly pesticide.

A face only a high octane Molotov could love: America’s $38 trillion national debt ‘exacerbates generational imbalances’ with Gen Z and millennials paying the price, warns think tank

And which cunts ended the government shutdown? Oh, those demonic democrats: THis is what they reaped. House Republican leaders ditch vote on ACA funding, all but ensuring premiums will rise

Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said Republicans worked on the issue throughout the weekend but could not come to an agreement with a group of members who want the funds extended.

Oh, that piracy, and that BRICS?

A tanker carrying Russian naphtha for Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA and at least four supertankers due to pick up crude cargoes in Venezuela have made u-turns after the U.S. seized a vessel carrying Venezuelan crude, ship monitoring data showed on Monday.

The U.S. Coast Guard last week intercepted and seized a very large crude carrier (VLCC) carrying some 1.85 million barrels of Venezuelan heavy oil sold by PDVSA, a sign of increasing friction between Venezuela and the U.S., which has ramped up pressure on President Nicolas Maduro.

The seizure left more than 11 million barrels stuck onboard other vessels in Venezuelan waters and has prompted some tanker owners to order u-turns to avoid problems, with an armada of U.S. ships patrolling the Caribbean Sea.

Russia? China? Fucking paper tigers and paper bears.

The US has not approved use of American rockets and missiles in EuroPULS launchers, the European version of Elbit System’s PULS, manufactured together with Germany’s KNDS, “Defense Express” reports. The US reportedly is concerned about “technological leaks.”

The report notes that the US has refused Germany’s request to operate its missiles on HIMARS and M270 MLRS rocket systems, both of which are manufactured by Lockheed Martin. This is a major move by the US because one of the most significant features of PULS is its compatibility with launching various rockets and missiles manufactured by different companies and countries. In general, PULS is a system that provides a comprehensive solution, capable of launching unguided rockets, precision munitions, and missiles at various ranges. The launcher is fully compatible with existing platforms, whether wheeled or tracked, thus allowing a significant reduction in maintenance and training costs, while it can hit targets at a maximum range of 300 kilometers.

Elbit wins Peruvian PULS artillery system tender

Elbit wins German army PULS artillery system tender – report

Just as Elbit has the cooperation with a large European company in the form of EuroPULS, Lockheed Martin also developed GMARS with Rheinmetall. This reflects how, at a time when the Israeli and US defense establishments cooperate, in part through $500 million each year through US military aid for joint projects in the field of air defense, the defense companies often find themselves as clear business rivals – even more so in Europe, where defense budgets are soaring.

Oh, that fucking BRICS. India?

Palo Alto Networks CEO Nikesh Arora says the cybersecurity giant remains committed to investments in Israel even after American-Israeli founder Nir Zuk stepped down earlier this year.

“One of the things I’ve learned in life is that you can’t separate the company from its founder,” Arora says at a press conference in Tel Aviv. “Our commitment to Israel has not changed despite the fact that Nir is not actively at Palo Alto.”

The Santa Clara, California-based cybersecurity firm founded by serial entrepreneur Zuk acquired Israeli firm CyberArk in July, in a deal valued at a staggering $25 billion. It marked the biggest-ever acquisition of an Israeli company after Google’s $32 billion purchase of Israeli-founded cybersecurity unicorn Wiz earlier this year. Zuk, who also served as CTO, decided in August to retire from Palo Alto after two decades

House negroes: Multiple human rights organizations are petitioning the National Basketball Association (NBA) to drop Dubai’s government-owned Emirates airline as a sponsor of the league’s in-season tournament, the Emirates NBA Cup, due to allegations of sportswashing.

“The NBA is letting itself be used as a pawn to distract people from what the UAE is doing in the world. This partnership is not innocent – it is sportswashing and it hides the suffering of millions of Sudanese people behind a trophy,” the Speak Out On Sudan petition, which is co-sponsored by 14 organizations, says on its website.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has repeatedly denied that it is playing any role in Sudan’s civil war, particularly accusations that it provides military, financial and logistical support to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has been accused of crimes against humanity by a number of human rights organizations.

That’s right, BRICS! Israeli Aid to Taiwan’s T-DOME Missile Shield Sparks Sharp Rebuke from China

Recent reports issued by Chinese intelligence agencies indicated increasing defense cooperation between Taiwan and Israel to develop the Taiwanese defense system “T-DOM”.

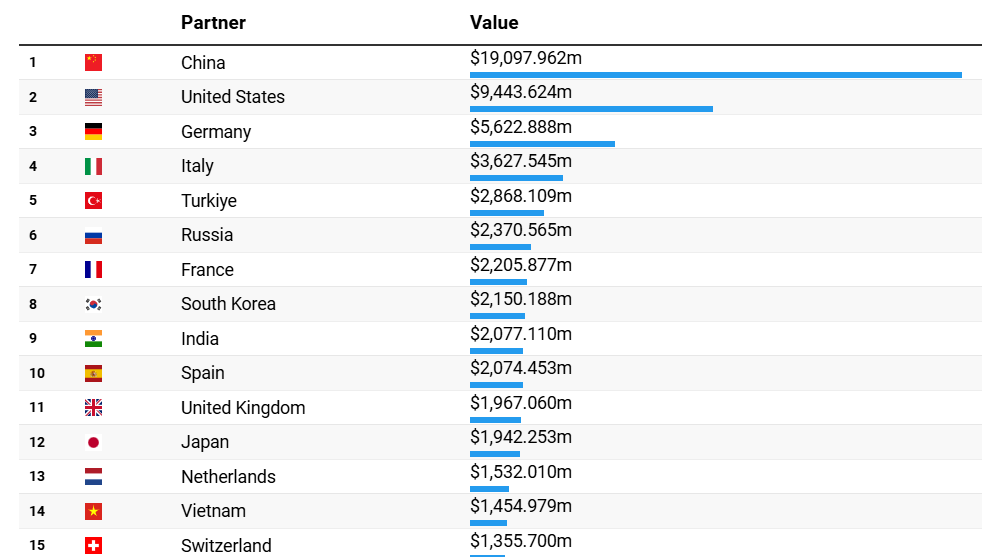

[Which countries sell the most to Israel?]

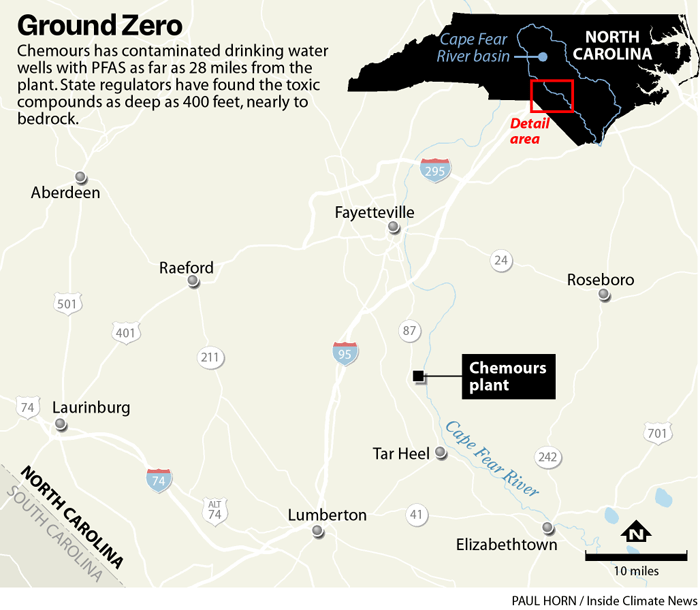

The troubling results opened a new front in a decades-long battle North Carolina environmentalists have been waging against PFAS in the state’s drinking water and air, soil and food.

In 2024, they celebrated when the Environmental Protection Agency under former President Joe Biden finally enacted the first drinking water standards for PFOA, PFOS, GenX, and three other related compounds.

But their victory was short-lived. During President Donald Trump’s second term, the EPA has weakened or gutted its few PFAS regulations. The agency has delayed implementation of drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS by two years, until 2031.

In September it also petitioned the U.S. Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia to rescind drinking water standards for several compounds, including GenX, which Chemours uses to produce non-stick cookware, food packaging, and firefighting foam.

The government shutdown earlier this fall delayed the court case. Lawyers for the agency and opponents of the rollback are scheduled to file additional legal briefs this month.

As the chemical industry applauds the rollbacks, Chemours is planning to expand its Fayetteville Works plant, the source of GenX and dozens of similar compounds, including TFA.

[Environmental epidemiologist Jane Hoppin’s research showed Wilmington residents were exposed to high levels of forever chemicals in the past]

Trump’s and MAGA’s and Minyan’s and Jew Zeldin’s AMeriKKKa: Scientists Say This Chemical Could Cause Irreversible Harm. It’s Everywhere in Eastern N.C.

The discovery of TFA in blood and water samples raises questions about Chemours’ role in adding to the pollution burden.

Read, kind people, kind folk in Africa, Latin America, READ:

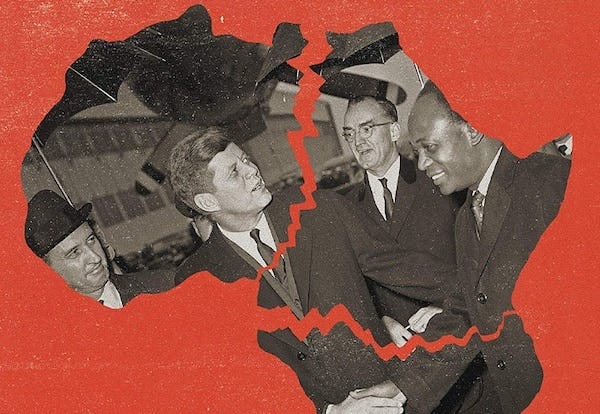

When Africa Tried to Unite and America Took It Personal

Susan Williams opens White Malice in the middle of the night—in Accra, March 1957, when the Union Jack comes down and the new flag of Ghana rises over Independence Square. If you read it like a liberal, it looks like a polite handover: Britain exits, Ghanaians cheer, a new anthem, some fireworks, the inevitable BBC commentary about “a new chapter.” But if you read it the way the CIA read it—and the way we have to read it today—that night in Accra is not just about Ghana. It is the first serious attempt in modern history to turn Africa into a united revolutionary force, and it terrifies the living hell out of the Western ruling class.

Williams doesn’t hit you over the head with theory; she just walks you through the scene. Nkrumah is not just celebrating a flag; he is announcing a project. Ghana’s independence, he insists, is meaningless unless it becomes the starting point of a continental transformation. In the crowd, you don’t just have Ghanaians; you have freedom fighters from across the continent, Black radicals from the diaspora, and representatives of struggles that haven’t yet “won” anything on paper but already understand what’s at stake. The message is simple: Ghana is not an end point; it is an opening move. Independence is not a ceremony; it is a signal.

This is where Western Marxists often start to get wobbly. They like to talk about “national liberation movements” in the abstract, but Williams shows you something much more concrete and dangerous to empire: Nkrumah is not content with putting a Black face on a colonial economy. He is talking about a United States of Africa, about planning, about industrialization, about cutting out the middleman between African labor and the world market. That means cutting out London, Paris, Brussels—and, increasingly, Washington.

The U.S. understands this faster than most of the Western left. While liberal commentators talk about “democratic transitions” and “post-colonial adjustments,” the American security state looks at Ghana and sees a nightmare in the making: a sovereign Black state with a radical leadership, a mass base, connections to liberation movements across the continent, and ambitions that stretch from Accra to Algiers to Luanda. This is not a colorful new stamp for their passport; it is a threat to the material infrastructure of imperial power.

Williams traces how quickly the Congo enters this picture. While Ghana raises its flag, the Congo is still a Belgian concession, a colony in everything but name. On paper it is scheduled to “transition” in a civilized way. In reality, it is the beating heart of Western war-making capacity. The Shinkolobwe mine has already supplied the uranium that incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The U.S. and its allies have no intention of letting any future Congolese government actually control that kind of leverage. When Nkrumah looks toward Congo and sees a brother in struggle, Washington looks at Congo and sees the fuse on its nuclear arsenal.

That’s the contradiction White Malice quietly lays out in its early chapters: on one side, an Africa trying to become a subject in world history; on the other, an American-led system determined to keep Africa as an object—raw material, cheap labor, and strategic real estate. Nkrumah is not naïve about this. He does the diplomatic dance, travels to Washington and London, makes speeches about partnership. But he is also organizing the All-African Peoples Conference in Accra, bringing together liberation movements, trade unionists, socialists, and revolutionaries to imagine exactly what the West fears most: a coordinated, continent-wide anti-colonial front.

Williams gives us a sense of the electric atmosphere in Accra during these gatherings. Delegates from still-colonized territories arrive with stories of massacres, prisons, and forced labor. Algerians speak of the French torture chambers; Kenyans speak of the British detention camps; South Africans speak of apartheid’s racial dictatorship. There are debates and contradictions—petty-bourgeois politicians rubbing shoulders with village organizers, Pan-African idealists arguing with hard-nosed trade unionists—but beneath it all is a simple shared understanding: colonialism is not a misunderstanding; it is theft enforced by terror. And the goal is not better management of the theft; the goal is to end it.

From the standpoint of Washington, this is intolerable. A liberated Ghana encouraging militant struggle across the continent is already bad enough. A Ghana that wants to help build a United States of Africa—which could control its own minerals, set its own prices, and align with the socialist camp—crosses the line from “decolonization” into “class war.” This is the point where the U.S. stops pretending that it is merely stepping into the shoes of the old European empires and starts building its own architecture of control.

Williams shows that the CIA doesn’t wait for things to “get out of hand.” Even as Western journalists write sentimental features about “young Ghana,” the Agency is already mapping out Ghana’s political scene, cataloguing allies, potential clients, and future enemies. Embassy reports obsess over Nkrumah’s links with the Eastern bloc, his openness to socialist ideas, the radical currents swirling around him. They are not worried about “democracy”; they are worried about power—who has it, who might take it, and whether they can stop it.

At the same time, they are watching Congo like a hawk. As the Belgians reluctantly accelerate independence, under pressure from Congolese mobilization and international embarrassment, the U.S. moves in behind them. This isn’t a rescue mission; it’s a merger and acquisition. Belgium may have been too crude, too racist even by Cold War standards, too obviously brutal. The U.S. intends to be more sophisticated. It will talk about stability, investment, and modernization while making damn sure nothing like genuine Congolese sovereignty over land, labor, or uranium ever materializes.

For Western Marxists, this is where White Malice should blow up a lot of lazy habits of thought. Too often, we treat African independence as if it were some side story to the “real” conflict between the U.S. and the USSR. Williams’s early chapters make it clear that, for Washington, Africa was not a peripheral theater; it was a central battlefield. Not out of moral concern for Africans, obviously, but because the whole structure of Western prosperity and military supremacy rests on continued control over African resources and markets. You cannot understand “monopoly capital” without understanding why the Congo’s uranium and Ghana’s bauxite matter. You cannot understand “Cold War strategy” without seeing why a united, socialist-leaning Africa had to be strangled in its crib.

Nkrumah grasps this in his own way. When he writes about neocolonialism, he is not writing about some psychological dependency or a metaphorical “colonial mindset.” He is describing a system in which formal independence masks continued economic and political subordination. Williams’s narrative gives flesh to that concept: the embassies, the World Bank missions, the “development experts,” the missionaries, the businessmen, the NGOs that begin to circulate through Accra and Leopoldville as the European flags come down. On the surface, it looks like international cooperation. Underneath, it is a new set of chains.

This is why the book’s early focus on ceremony matters. The West is very good at turning history into theater. British and American newsreels show smiling crowds and waving flags; they narrate decolonization as a moment of Western generosity, a sign that the “free world” is living up to its values. But Williams keeps showing you the other scenes: the plans drawn up in Washington conference rooms, the cables from CIA stations, the quiet meetings with “moderate” African politicians groomed to replace the radicals. Behind the ballet of diplomacy is the choreography of counterrevolution.

From a guerrilla intellectual standpoint, the lesson is straightforward. When an oppressed people finally forces the empire to loosen its grip, the empire does not retire to a villa and write its memoirs. It changes costume. It trades the pith helmet for the development briefcase, the colonial charter for multilateral agreements, the direct rule for indirect rule—through “aid,” through debt, through proxies. In the 1950s and early 1960s, as Williams documents, the U.S. is busy mastering this costume change in Africa.

The tragedy—and the opportunity—is that many on the Western left still haven’t caught up. They understand that colonialism was bad, of course. They might even have a Che poster on the wall. But when they look at Ghana, Congo, or any of the states that emerged from that period, they often see “failed national projects,” “corruption,” or “ethnic conflict” before they see the deliberate sabotage of an entire continent’s attempt to become free. They see the rubble, but not the demolition crew. White Malice hands us the blueprints of that demolition.

So Part I of this review has one principal job: to reset the frame. Ghana’s independence is not a sweet story about the inevitable march of freedom; it is the opening of a front in a global class war. The Congo is not a chaotic backdrop to Cold War maneuvering; it is the strategic heart of an imperial economy. Nkrumah is not an overambitious dreamer who flew too close to the sun; he is a revolutionary statesman who understood that Africa had to unify or perish under the heel of the same powers that had carved it up at Berlin.

Williams, to her credit, gives us the evidence. She digs through archives, cables, and testimonies to show how quickly the U.S. state moved to encircle Ghana and Congo, to monitor every radical initiative, to pre-empt every serious attempt at autonomy. Our task in this Weaponized Intellects review is to do what her liberal framework stops short of: to name this pattern for what it is—neocolonial counterinsurgency in defense of Western monopoly capital—and to insist that anyone serious about socialism, multipolarity, or peace has to start from that truth.

In other words: when Africa tried to unite, the United States of America declared war. Not always with marines on the beaches, but with spies, saboteurs, front organizations, and “friends” in high places. White Malice lets us see the opening moves of that war up close. The rest of the book—and the rest of this review—will show just how far the empire was willing to go to make sure that a United States of Africa remained a threat on paper, not a reality on the ground.

The Reptile Learns to Smile: How the CIA Built a New Colonial State in Africa

By the time Susan Williams moves deeper into White Malice, the old colonial machinery is collapsing in public view. Flags are coming down. Governors are flying home. Europe is bruised, bankrupt, and exhausted. But in the shadows, something far more dangerous than the Belgian gendarme or the British colonial office is taking shape. A new imperial apparatus—slicker, quieter, and infinitely more poisonous—is being assembled brick by brick. Williams never calls it by its true name, but we will: the infrastructure of U.S. neocolonialism.

What the early chapters showed us in outline is now revealed in detail: the CIA didn’t simply inherit empire; it upgraded it. The Agency studied Europe’s old colonial techniques, then redesigned them for an age when open rule had become politically inconvenient. If the British empire ruled by occupying the soil, the CIA would rule by occupying the space between people—their schools, their newspapers, their radios, their universities, their unions, their parliaments, their churches, their armies, their dreams of modernization.

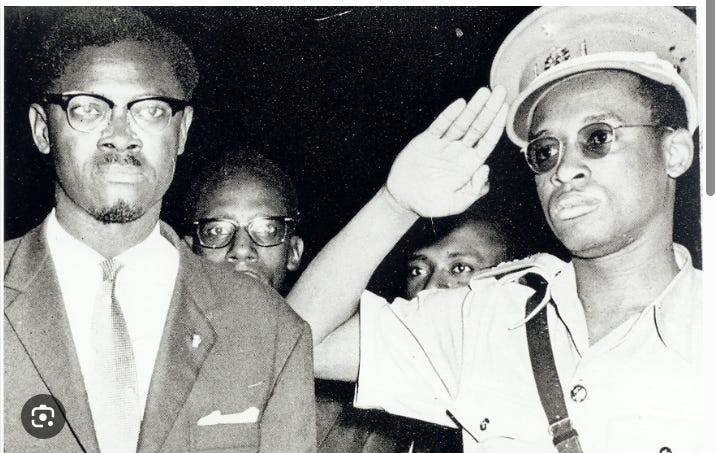

Williams walks us into this architecture step by step. There is the Africa Division of the CIA, established not out of curiosity but out of panic, its analysts convinced that Africa had become “the real battleground” of the Cold War. There are the thick binders of psychological profiles on African leaders—Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Sékou Touré—treated like chemical hazards whose spread needed to be contained. There are cables buzzing between Washington, Leopoldville, Accra, and London, mapping influence networks with the precision of a surveyor charting out new property lines. And then there are the softer tools—universities offering scholarships, foundations establishing research centers, press agencies distributing “balanced” news, churches opening missions, NGOs arriving with clipboards and smiles—all funded, guided, or quietly coordinated by the same hand.

In this part of the review, we have to linger on these quieter tools because Western Marxists rarely do. They prefer the dramatic—coups, assassinations, invasions—because those fit neatly into the narrative of U.S. imperial overreach. But the subtle operations, the ones dressed up as benevolence, as philanthropy, as education—these are the operations that break nations before a single bullet is fired.

Consider the cultural fronts Williams describes. American academics flood African universities under the banner of exchange programs. African students are flown to the United States not just to study, but to be socialized into a worldview in which capitalism equals modernity and socialism equals chaos. Radio stations pop up with American equipment and “local” staff, broadcasting messages designed to make Africans doubt their revolutionaries and trust the white hand that enslaved them yesterday. Newspapers receive funding conditioned on the selection of “properly balanced” editors. Christian missions preach humility to the oppressed and patience with the oppressor. All of this is counterinsurgency done with a smile—a velvet glove over a steel fist.

Williams gives us the facts: the infiltration of political parties, the recruitment of journalists, the grooming of union leaders, the bribing of bureaucrats, the infiltration of student movements, the sponsoring of conferences, the wiretapping of diplomats at the United Nations. She uncovers letters, transcripts, travel memos, budgets, and blandly sinister program descriptions. But where she stops is where we must begin. We must call this by its true name: a new class project of Western bourgeois domination. A class project that required not merely the defeat of socialism but the permanent subordination of Africa to the needs of U.S. monopoly capital.

And this is where the section title earns its keep. Marx once said that the bourgeoisie produces its own gravediggers. In Africa, the bourgeoisie produced its own reptiles. In Williams’s account, the CIA slithers through the continent—coiling around newspapers, slipping into ministries, whispering into the ears of future presidents, offering scholarships with one hand while preparing poison with the other. But here is the trick: the reptile learns to smile. It masters the language of development, democracy, good governance, and modernization. It perfects the art of sounding like a partner while acting like a colonizer. It creates a class of Africans who speak the imperial language better than their own. It buys loyalty where it cannot impose it. It bribes where it cannot convince. It lies where it cannot buy.

This is not simply espionage. This is statecraft—the forging of a new global order in which the U.S. presides over a decolonizing world by making sure decolonization never becomes liberation. And here lies the first major lesson for Western leftists: the U.S. state did not fear African communism. It feared African sovereignty. It feared the possibility that Africans might govern themselves in accordance with their own interests, not Washington’s quarterly reports. It feared a world in which Africa could align with the socialist camp not out of puppet loyalty but out of shared historical experience and common material needs.

As we move through Williams’s chapters, another recurring detail becomes impossible to ignore: the sheer scale of surveillance. Nearly every African leader of significance is under watch. Letters are intercepted. Private meetings are monitored. Allies are cultivated. Enemies are catalogued. Even neutral states become laboratories of influence. By the time Nkrumah writes his famous warning that “the essence of neocolonialism is that the state which is subject to it is… independent in name only,” the CIA has already proven him right.

And yet, the Agency is not omnipotent. We cannot romanticize imperial power. What Williams uncovers are not the movements of a godlike entity but the frantic labor of an empire sweating to keep history from escaping its grasp. The U.S. acts not from confidence but from fear—fear that Ghana might industrialize under socialist principles, fear that Congo might control its uranium, fear that Guinea might align with the Eastern bloc, fear that a united Africa might control its own markets. Every covert program, every front organization, every forged dossier is a confession of imperial vulnerability.

That is the irony that Marx would savor, and that Rodney would underline for the students in Dar es Salaam: the very power of the imperial state reveals its weakness. If the system were secure, the CIA would not need to spend fortunes grooming Kenyan elites, bribing Congolese ministers, or bugging Ghanaian telephones. Empire works this hard only when the oppressed are close to breaking free.

For us—writing from inside the belly of the beast—the lesson is clear. Empire today still smiles. It smiles through Silicon Valley philanthropies, through IMF loans, through State Department “civil society partnerships,” through NGOs promoting “democratic resilience,” through scholarships and fact-checking grants and journalism workshops. It is the same reptile, only better dressed. And the task of revolutionary intellectuals—our task—is to strip away the smile and show the fangs beneath.

White Malice shows the birth of this new imperial architecture. In the next part of this review, we will examine how this architecture was deployed with full force in the Congo, where the U.S. and its allies staged one of the most violent counterrevolutions of the twentieth century. But before we go, let this be the conclusion of Part II: the CIA did not arrive in Africa to defend democracy. It arrived to pre-empt revolution. And the sooner the Western left internalizes that truth, the sooner it can stop apologizing for the empire it claims to oppose.

The Killing of Lumumba and the Blueprint of Counterrevolution

By the time Susan Williams escorts us into the Congo crisis, the stage has already been set. The CIA has mapped the terrain, catalogued the players, bought off the pliable, marked the uncompromising for elimination, and rehearsed its lines for the global audience. What unfolds next is not improvisation. It is the first great neocolonial counterrevolution of the postwar era, executed with such precision, cruelty, and bureaucratic calm that every future Western intervention—from Chile to Grenada to Libya—reads like a footnote to this original script. And at the center of this script stands the figure the West could not abide: Patrice Lumumba.

Williams does not romanticize him, nor should we. Lumumba is not a saint; he is a worker-intellectual trained by experience, sharpened by humiliation, and carried forward by the force of the Congolese masses. He understands something that the Belgians, the Americans, and—let’s be honest—many Western Marxists still fail to grasp: sovereignty is not a speech. It is a seizure of power. It is control over territory, resources, borders, the army, the economy, and the story a people tells about itself. And in the Congo of 1960, sovereignty is impossible without confronting the most ruthless coalition of imperial interests on the planet.

The Belgians exit in a fury of sabotage. The Force Publique mutinies; Katanga, the mineral-rich jewel in the Belgian crown, declares secession under Moïse Tshombe; Western corporations migrate from colonial administration to covert influence; and diplomats whisper that Lumumba is too “emotional,” too “radical,” too “unpredictable” for their taste. This is imperial code for: he refuses to be managed. He refuses to privatize victory. He refuses to turn the Congolese people’s uprising into a polite negotiation between elites. He refuses to turn Congo into a blank contract for Brussels, London, and Washington to fill out.

Williams brings us into the Round Table Conference, the hurried “transition,” the Belgian panic, the messy birth of the new state. But the important thing is this: Lumumba enters office with a mandate from the masses and a target on his back. He calls in the UN not because he trusts it but because he hopes it can restrain Belgium. Instead, it restrains him. The UN’s “neutrality” becomes a buffer protecting secessionists armed by Western interests. Dag Hammarskjöld speaks of peace while enabling the slow-motion strangulation of the elected Congolese government. A thousand Western commentators cheer this neutrality. They still do.

The CIA does not hide its intentions in private. Williams documents cables where officers describe Lumumba as “a mad dog,” “a Castro-like figure,” or “a grave threat to the interests of the free world.” These are the labels the U.S. intelligence state reserves for leaders who dare to govern on behalf of their own people. In public, the U.S. expresses “concern” about stability. Behind closed doors, Allen Dulles signs off on an assassination program. This is how imperialism conjugates verbs: they destabilize, you are unstable.

Here the book turns surgical. Williams walks us through YQPROP, WIROGUE, QJWIN, and the cluster of covert operations whose names sound like pharmaceutical products but deliver something far deadlier. You get money for bribes, laboratories for poison, logistics for kidnapping, forged papers, bogus cables, Belgian officers “on loan,” and African intermediaries groomed to do the dirtiest work. If the colonial era was ruled by force and arrogance, the neocolonial era is ruled by procedure and deniability. Bureaucrats fill out forms authorizing murder. Diplomatic pouches carry toxins instead of treaties. The empire of merchants has become an empire of hitmen wearing suits.

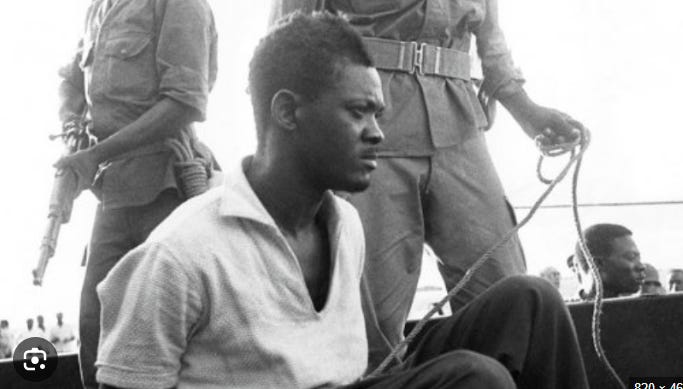

And yet what makes the Congo crisis so revealing is not simply that Lumumba is killed—it is how many ways the West prepared to kill him. Williams describes poison kits prepared by Sidney Gottlieb, the CIA’s resident alchemist of death; plots to contaminate Lumumba’s toothpaste; schemes to kidnap him in the night; coordination with Belgian security services more than willing to finish the job. Assassination becomes a multicontinental project—an early example of what activists today call “joint operations.” Lumumba’s body had to disappear so that Western capital could remain.

The tragedy—and the indictment—is that Western Marxists still debate whether this was a Cold War “miscalculation.” To read Williams is to see clearly: there is no miscalculation here. There is only strategy. Congo was too rich, too central, too symbolic to allow a freely chosen, mass-backed, socialist-leaning leadership to live. The question was never whether Lumumba would be removed; the question was which method would be most convenient. Poison? A staged escape gone wrong? Delivery to his enemies? Belgian commandos? “Internal factional violence”? The point was not justice. The point was narrative control.

Williams details the final sequence with chilling clarity: Lumumba’s arrest, humiliation, beatings, transfer, and torture; the perverse parade of officials ensuring that responsibility would be diffuse and accountability impossible; the Belgian officers standing by as Congolese collaborators pulled the trigger; the secret burial; the later destruction of his body with acid. It is a lynching carried out by a geopolitical system, not a mob. It is the colonial logic updated for television. The West kills the man, then kills the evidence, then kills the story, then accuses the victim of “instability.”

But this section of the review is not a lament. It is an analysis of a method. Because as Williams shows, Congo becomes the template for imperial crisis management across the Global South. You begin with disinformation—Lumumba as communist, Lumumba as dictator, Lumumba as threat. You encourage secession, factionalism, regionalism—divide the nation, then declare the nation ungovernable. You offer mediation through “neutral” institutions—UN missions, aid agencies, technical advisers—whose actual role is to freeze revolutionary momentum. You cultivate local elites with promises of recognition. You demonize the mass base. You isolate the leadership. And when all else fails, you pull the trigger and call it fate.

Every future coup carries the genetic imprint of Congo 1960: Goulart in Brazil, Allende in Chile, Sankara in Burkina Faso, Aristide in Haiti, Zelaya in Honduras, Morales in Bolivia, the color revolutions in Eastern Europe, the NATO war against Libya, the hybrid warfare against Venezuela. The tools evolve—social media psyops, sanctions, “fact-checking,” cyber operations—but the imperial relation remains unchanged. Congo is not a relic; it is a manual still in circulation.

And here is the lesson for multipolar fantasists: empire does not relinquish Africa because of new geoeconomic winds. It adapts. It morphs. It invests in new technologies of domination. Williams shows us the prototype. Today’s AFRICOM, “stabilization partnerships,” counterterrorism coalitions, and billionaire philanthropies are simply the grandchildren of YQPROP and WIROGUE—still advancing the same objective: prevent African sovereignty from becoming African power.

But Williams, as thorough as she is, writes like a historian. We write as revolutionaries. So let us be explicit: Lumumba was not only murdered by Belgium and the CIA. He was murdered because he believed that the world could be reorganized around the needs of the colonized. He was murdered because he refused to turn Congo into a franchise of Western capitalism. He was murdered because he wanted the minerals beneath his feet to nourish his people and not fuel the bombs of the empire. He was murdered because he said, clearly and calmly, that Africa is not the property of Europe. And for that simple truth, the West condemned him to death.

Lumumba’s assassination was the foundational act of the neocolonial order. It taught African elites the price of disobedience. It taught Western liberals the art of looking away. It taught the CIA that coups were cheaper than colonies. And it taught the global ruling class that if you kill a revolutionary young enough, the movement might still die with him. What they could not anticipate was that Lumumba’s ghost would take up permanent residence in every African struggle—from Amílcar Cabral to Samora Machel to Thomas Sankara to today’s pan-Africanists fighting digital colonialism.

So Part III ends with a simple but necessary conclusion: Lumumba was not defeated. He was targeted, isolated, and murdered by the full weight of Western imperial power. And yet the very ferocity of that attack proves what the West feared most: that the Congo, if liberated, could have shifted the balance of the world. His murder is a wound in the global working class—a wound we are still obliged to heal. Our task as readers, organizers, and defectors from empire is not to mourn him endlessly but to understand why he was killed, and to ensure that the system that killed him does not survive us.

Black Skin, White Scripts: How Empire Recruits the Colonized to Police Their Own Liberation

By the time Susan Williams leads us into the cultural and intellectual front of the Cold War in Africa, the story shifts from poison vials and coup plots to something far more subtle—and in many ways far more dangerous. If the assassination of Lumumba represents the hard power of neocolonialism, then the soft power documented in these chapters is its cultural bloodstream: the quiet co-optation of African and African-descended talent into the reproduction of imperial rule. And this is where the Western left often loses the plot entirely. They recognize CIA coups. They do not recognize CIA classrooms.

Williams shows us that the CIA did not only build assassins; it built intellectuals. It built journalists, editors, publishers, professors, playwrights, radio hosts, and “civil society leaders.” It built the cadre that would narrate Africa to the world and narrate the world to Africa. It built a class of Africans who, without ever meeting an American handler, carried Washington’s worldview inside their vocabulary like a virus—repeating its fears, echoing its frameworks, and mistaking its interests for universal truth. This was not mind control in the lurid MKULTRA sense (though the same offices funded both). It was something closer to spiritual engineering: teaching colonized people to desire their own subordination.

The names that appear in Williams’s research—AMSAC, the Transcription Centre, International Press Institute, Congress for Cultural Freedom—look innocent on the page. They sound like something your professor might praise for “promoting African literature” or “fostering intellectual exchange.” And that is exactly what makes them lethal. These were weapons disguised as scholarships, grants, and opportunities. These were laboratories where empire experimented with shaping the postcolonial mind. These were models of what we now call NGO imperialism: organizations claiming independence but funded by the very governments seeking to control Africa’s political, economic, and ideological future.

And the faces attached to these projects were often Black. That is the brilliance—and the horror—of the operation. To sell the idea that revolution is chaos, you need a respectable African voice to say it. To convince the public that Nkrumah is dangerous, you need a Ghanaian intellectual to warn about “one-party tendencies.” To argue that pan-Africanism is unrealistic, you need an African scholar funded to study “tribalism.” To drown out the cries of Lumumba’s supporters, you need an African columnist writing about “responsible leadership.” Empire understands optics. It always has. It knows white hands on the puppet strings are too conspicuous. Better to recruit the colonized and have them repeat imperial narratives in their own accents.

Williams does not condemn these individuals. She does not have to. The archive does it for her. There are memos from the CIA’s Africa Division praising the effectiveness of funded publications. There are cables noting how certain African newspapers consistently echo U.S. positions. There are reports measuring the political orientation of African student leaders returning from American universities. There are budgets listing payments for conferences aimed at “moderates” and “responsible voices.” This is not conspiracy theory. This is public documentation. This is class struggle waged through typewriters and microphones.

But here we must push beyond Williams’s tone and name what she gestures toward: the production of a comprador intelligentsia. A class not defined by skin color but by political function. A class whose job is to translate imperial ideology into a language palatable to the colonized. A class that serves as a buffer class—between the revolutionary aspirations of the masses and the violent anxieties of the imperial state. A class that preaches moderation while the empire drops bombs.

And this is where the Western left must confront an uncomfortable truth. The problem is not simply that the CIA funded African writers and scholars. The problem is that the entire ideological ecosystem of the West—from journalism to academia to philanthropy—remains structured to reproduce imperial frameworks. Many Western Marxists uncritically read the output of these same cultural fronts. They quote the magazines the CIA bankrolled. They take as neutral analysis the writings of African intellectuals whose careers were built on Western grants. They watch documentaries funded by the same foundations that helped undermine Lumumba. In other words, they drink from contaminated springs and wonder why their theories taste like liberalism.

Williams invites us into the contradictions of the cultural Cold War: Louis Armstrong touring Africa while the U.S. government hounds Black radicals at home; African Studies departments celebrating “modernization” while revolutionaries like Amílcar Cabral, Samora Machel, and Thomas Sankara articulate a far more profound, Marxist understanding of liberation. She shows us debates at literary festivals funded by CIA pass-throughs—debates meant not to strengthen African liberation but to generate an African elite acceptable to Washington.

And here we must extend the analysis into the present. Today’s NGOs, think tanks, DEI offices, “democracy promotion” programs, global fact-checking networks, and billionaire philanthropies play the same role as AMSAC and the Congress for Cultural Freedom. They shape discourse. They define “acceptable” radicalism. They domesticate revolutionary anger by converting it into professional opportunities. They tell Africa to rise—just not in any direction that threatens Western extraction. They produce an aesthetics of liberation and a politics of obedience. And too many Western leftists applaud this because they mistake representation for emancipation.

White Malice offers us receipts. It shows how quickly the U.S. learned to fight revolution with culture rather than guns—because culture leaves fewer fingerprints. Guns kill bodies; culture kills possibilities. Culture kills the dream of unity before it can be spoken aloud. Culture kills the trust between the people and their revolutionary leaders. Culture kills the idea that the colonized might define their own future.

In every page of these chapters, we see the same project unfolding: to make Africa’s educated classes the ideological supply chain of empire. A continent that had just begun to speak with its own voice is suddenly being translated back into the language of its oppressors. Not because Africans lacked creativity or intellect—they had more than enough—but because empire knew that control of the narrative meant control of the future.

And so Part IV ends on a necessary, sharp conclusion: the CIA did not only produce the assassins who killed Lumumba; it produced the pundits who explained why his death was inevitable. It produced the professors who wrote Africa into Western paradigms. It produced the journalists who mocked Nkrumah’s dreams. It produced the editors who published the “responsible” critiques of socialism. It produced the cultural workers who populated the imagination of the newly independent states with liberal caution and capitalist common sense.

For anyone claiming to stand with the global working class, this is the warning White Malice places in our hands: the most effective agents of imperial domination do not always wear uniforms. Sometimes they carry pens. Sometimes they win literary prizes. Sometimes they host panel discussions. And sometimes, with all sincerity, they tell you that liberation is too ambitious—right before accepting another Western grant.

How to Break a Continent: The War on Pan-African Socialism from Congo to Ghana to Angola

By the time Susan Williams guides us into the later sections of White Malice, the narrative widens. We are no longer looking at a single operation or a single country. We are seeing a continental strategy—an imperial doctrine formulated not in public policy papers but in covert action budgets, intercepted cables, and the debris of murdered revolutions. Congo was not an anomaly; it was a prototype. Lumumba was not the only target; he was the opening salvo. What the United States, Britain, Belgium, and their corporate patrons feared was not any one leader. They feared an alignment: a revolutionary Ghana, a sovereign Congo, an armed Angola, a socialist Guinea, a united Africa charting its own industrial and political path. And they feared the man who understood that alignment best: Kwame Nkrumah.

Williams walks us through this next phase with the dispassion of an archivist, but make no mistake—these chapters describe a counteroffensive worthy of any military theater. As Cuba intervenes in Angola, as independence movements grow teeth, as Nkrumah moves to deepen Ghana’s economic independence and fortify continental unity, the West enters its most aggressive period of covert destabilization. If Congo was the test case, Ghana becomes the prize. And Angola becomes the continental battlefield where the West tries to avenge its humiliation in Cuba and pre-empt its nightmare in southern Africa.

Start with Ghana. Nkrumah is not just head of state; he is the architect of a Pan-African project that threatens to flip the world economy on its head. Under his leadership, Ghana backs liberation movements, funds scientific research, builds industrial infrastructure, and edges closer to nuclear development. The Western press mocks him as a dreamer. Washington classifies him as a threat. MI6 calls him “unstable.” The CIA quietly calls him “dangerous.” These are all synonyms for: he refuses to govern according to our interests.

Williams uncovers the layers of plotting around Ghana with the kind of meticulous detail only archival research can provide. We see British intelligence cultivating opposition leaders. We see U.S. officials financing anti-government unions, radio stations, and newspapers. We see embassy staff working hand-in-hand with dissident officers. We see State Department memos framing Ghana’s continental activism as “subversive.” And then we see the final act: a coup timed to Nkrumah’s absence from the country, executed with surgical precision, blessed instantly by the West, and followed by rapid efforts to dismantle everything Ghana had built toward socialism and self-reliance.

And yet, as important as Ghana is, Williams forces us to widen our gaze to Angola, where Western fear of African socialism becomes outright panic. Angola is not merely a site of decolonization; it is a collision point between competing futures. On one side: the MPLA, grounded in Marxist politics, disciplined, mass-rooted, backed by Cuba and later the USSR. On the other: Holden Roberto, a man CIA officers practically boast about inventing, grooming, and deploying as “America’s Angolan.” Add South African apartheid’s military machine to the mix, plus Zaire under Mobutu acting as the West’s regional enforcer, and Angola becomes the crucible of African liberation and neocolonial retaliation.

Williams cites John Stockwell, the former CIA officer who breaks with the Agency and later exposes the truth. His testimony is devastating because it confirms what revolutionaries had been saying for decades: that the U.S. escalated the war, armed factions to the teeth, pumped millions into covert operations, and lied to Congress and the public about its involvement. Stockwell’s most damning observation is painfully simple: the MPLA told the truth; the U.S. lied. The revolutionaries were transparent; the counterrevolution hid behind press releases. Empire accuses its victims of the crimes it commits.

That is the connective tissue across these battlefields. The West frames Nkrumah as authoritarian while installing military juntas. It frames Lumumba as unstable while orchestrating mass terror. It frames the MPLA as aggressive while arming South Africa’s white supremacist regime to invade Angolan territory. The lies are not mistakes; they are weapons. They are the ideological air cover for ground operations.

What makes this section of the book so powerful—and so damning—is that Williams reveals not isolated meddling but continuity. The same names recur across decades. The same intelligence officers rotate through multiple African stations. The same corporations shift investments from Ghana to Congo to Angola depending on which resistance movement threatens their profits. The same British and Belgian diplomats reappear as advisers, consultants, troubleshooters in regimes friendly to the West. Empire is nothing if not persistent.

And this is where Western Marxists must once again confront their blind spot. Too many still treat Africa as a series of disconnected national tragedies: coup in Ghana, assassination in Congo, war in Angola, collapse in Liberia, apartheid in South Africa, structural adjustment everywhere. But Williams shows the throughline: from the uranium of Shinkolobwe to the oil of Cabinda; from the bauxite of Ghana to the diamonds of Zaire; from Cold War paranoia to neoliberal consolidation. It is one system, one strategy, one class war prosecuted across generations.

For Africa, this strategy was not merely about resources. It was about preventing what the CIA called “the Nkrumah effect”: the spread of revolutionary confidence among colonized peoples. A sovereign Ghana might inspire a sovereign Togo, which might inspire a sovereign Niger, which might inspire a sovereign Angola. A liberated Africa might join the socialist camp as a bloc—or, worse for the West, it might form its own pole. The nightmare of Washington was not African communism. It was African unity.

Williams’s chapters on Nkrumah’s final years are especially haunting. Here is a man who predicted everything the West would do to him. Here is a leader who understood neocolonialism not as a metaphor but as an administrative system. Here is a visionary who saw the coup coming, who warned that Africa must industrialize or perish, who argued that Pan-Africanism was not a dream but a survival strategy. And here he is, deposed not by the will of the Ghanaian masses but by the coordinated machinations of the CIA, MI6, reactionary officers, comprador elites, and an imperial press corps that cheered the dismantling of a revolutionary project they never understood.

At this point in White Malice, the pattern is undeniable: whenever Africa tries to stand upright, empire breaks its knees. Whenever a leader speaks of unity, they are labeled a threat. Whenever a movement declares sovereignty, the IMF appears with debt chains. Whenever a people seizes the right to control their own resources, a coup mysteriously follows. Angola was attacked because it armed its revolution. Ghana was overthrown because it planned its own future. Congo was destroyed because it held the material key to Western power.

And yet this is not a story of defeat. The resistance was fierce. The MPLA survived. Guinea held its line. Tanzania remained a base for liberation movements. Cuba fought—and won—in Angola. Nkrumah left behind a body of theory that continues to arm revolutionaries. Lumumba’s name still electrifies the oppressed. Sankara would later rise and declare that imperialism must be killed, not reformed. History does not move only through empire’s victories; it also moves through the stubborn memory of the colonized.

So Part V concludes with the necessary clarity White Malice demands of us: Africa was not “destabilized.” Africa was attacked. Africa did not “fail.” Africa was sabotaged. Ghana did not “overreach.” Ghana was targeted. Angola did not “descend into chaos.” Angola was invaded. These are not tragedies. They are crimes. They are not unfortunate detours. They are deliberate strategies of counterrevolution deployed to prevent a new world from being born.

For revolutionaries today—for the global working class, multipolar forces, and especially those struggling inside the U.S.—the lesson is blunt: if you attempt what Nkrumah, Lumumba, and the MPLA attempted, the empire will come for you with every tool it has. But the equal and opposite truth is this: if they could inspire such coordinated violence from the world’s superpowers, then they were close to shaking the foundations of that world. Close enough that the empire panicked. Close enough that the empire exposed its own fear. And close enough that their struggle—and the evidence Williams has preserved—remains a weapon waiting to be reclaimed.

White Malice Is Not History—It Is Policy

Susan Williams closes White Malice with a sense of moral unease. The documents are now public. The cables are declassified. The lies are exposed. And yet, the world that produced them remains intact. This is where our review must refuse the comfort of closure. Because if there is one lesson that runs like a live wire through every page of this book, it is this: what happened to Africa in the age of formal decolonization was not an aberration. It was rehearsal. It was calibration. It was the early architecture of a system that still governs the world in 2025.

Williams gives us the evidence. She proves—beyond reasonable doubt—that the United States and its allies dismantled African liberation movements through assassination, coups, propaganda, cultural engineering, economic pressure, and proxy war. She shows how the CIA functioned as the managerial arm of empire, coordinating governments, corporations, foundations, media, and militaries into a single counterrevolutionary force. She demonstrates that African sovereignty was never defeated by internal weakness alone, but by overwhelming external intervention designed precisely to make liberation impossible. On these points, the record is airtight.

Where Williams stops is where revolutionaries must begin. She treats these revelations as a scandal of the past—an indictment of secrecy, excess, and moral failure. We treat them as a diagnosis of the present. Because nothing in White Malice belongs safely to history. The methods have not disappeared. They have been normalized. The targets have not vanished. They have multiplied. The language has changed—“democracy promotion,” “rules-based order,” “civil society,” “counterterrorism,” “anti-disinformation”—but the function remains identical: to prevent the colonized and the exploited from controlling their own futures.

This is the point Western Marxists must finally confront. You cannot build a serious theory of capitalism, socialism, or multipolarity while treating Africa as a footnote. You cannot talk about imperial decline while ignoring how empire survives by disciplining the periphery. And you cannot speak of internationalism while refusing to reckon with the fact that the Western left itself has been shaped—ideologically, institutionally, and materially—inside the very system Williams exposes. White Malice is not just a book about Africa. It is a mirror held up to the Western left, revealing how much it still misunderstands about power.

Nkrumah warned that neocolonialism would be harder to detect than colonialism because it would wear the mask of independence. Williams shows us that mask being forged in real time. We see how formal sovereignty was granted while economic control was retained. We see how flags were raised while minerals remained under foreign command. We see how parliaments were inaugurated while armies were infiltrated. We see how culture was celebrated while revolutionary consciousness was smothered. This is not hypocrisy; it is design. And it explains why so many postcolonial states appear “independent” yet remain structurally unable to break with imperial accumulation.

For the global working class and peasantry, the implications are immediate. The poverty of the Global South is not the residue of underdevelopment; it is the product of overdevelopment elsewhere. The debt regimes, trade rules, sanctions systems, and military alliances of today rest directly on the counterrevolutionary victories documented in this book. The IMF does not arrive by accident. The NGO does not operate in a vacuum. The coup does not come out of nowhere. Each is a modern descendant of the operations Williams painstakingly reconstructs.

And for those of us inside the imperial core, the responsibility is even sharper. The CIA operations in Africa were not funded by abstraction. They were funded by surplus extracted from workers and consumers in the United States and Europe, recycled through banks, corporations, and state budgets. The comfort of the Western working and middle classes was materially linked to the suppression of African liberation. This is the material basis of what passes for “ignorance” on the Western left. It is not merely ideological confusion; it is structured benefit.

To read White Malice honestly is to be forced into a choice. Either you treat it as a tragic story of past excesses—something to be regretted, archived, and moved on from—or you recognize it as a user’s manual for contemporary empire. Either you lament Lumumba and Nkrumah as fallen heroes, or you ask why anyone who resembles them today is immediately labeled a dictator, sanctioned, destabilized, or erased. Either you accept the liberal fantasy that the system can be reformed, or you accept the far more unsettling conclusion that the system works precisely as intended.

Williams herself gestures toward this unease in her closing pages. She notes the persistence of secrecy, the reluctance of governments to accept responsibility, the ease with which violence is buried under procedural language. What she does not say—but what the evidence demands—is that empire has no incentive to confess. It has only an incentive to evolve. The tools used against Africa in the 1950s and 1960s have since been refined, digitized, and globalized. Counterinsurgency has moved from villages to platforms, from pamphlets to algorithms, from radio broadcasts to social media moderation policies. The logic, however, is unchanged.

This is why White Malice matters so profoundly today. It punctures the myth that imperial violence belongs to another era. It reveals the continuity between colonial conquest and contemporary “global governance.” It exposes the lie that Western power is benign when unchecked. And it arms us with the historical clarity necessary to understand why so many struggles—from Palestine to Haiti, from the Sahel to Venezuela—are met with the same repertoire of coercion, distortion, and punishment.

The task of a Weaponized Intellects review is not to admire research. It is to transform knowledge into orientation. And the orientation this book demands is unmistakable. There can be no socialism without anti-imperialism. There can be no multipolar world without dismantling neocolonial control. There can be no honest Western left that does not break decisively with the institutions, narratives, and privileges that empire uses to reproduce itself. Neutrality is not a position; it is a function.

White Malice is a warning written in declassified ink. It tells us what the empire does when its foundations are threatened. It tells us how far it is willing to go to preserve control. And it tells us, indirectly but unmistakably, that the fear driving these operations was not irrational. Africa, united and sovereign, could have changed the world. That possibility was close enough to require murder on a continental scale. That is the measure of its power.

The final lesson, then, is not despair but responsibility. If empire expended such effort to crush African liberation in the twentieth century, it is because liberation was—and remains—possible. Our task is not to mourn what was destroyed, but to understand how it was destroyed so that it cannot be destroyed again. To side openly with the colonized. To defect from the logic of empire. To build internationalism not as sentiment, but as strategy. White Malice does not ask us to remember. It demands that we choose.

+—+

More, China, read MORE: A review of “White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa” by Susan Williams