and, my fellow warriors (NOT): Oh, those fucking mainstream cocksucking writers!

Oct 25, 2025

New YORK? Jeww York Crimes: New York Times makes Joseph Kahn its 5th Jewish executive editor since 1964

Kahn’s father, who founded Staples, favored Holocaust education in his philanthropy.

“Joseph grew up in the Jewish tradition,” spokesperson Danielle Rhoades Ha told said Tuesday in an email. “Though he is not a practicing Jew he identifies as Jewish.”

The past Jewish executive editors were A.M. Rosenthal (1977-1986), Max Frankel (1986-1994), Joseph Lelyveld (1994-2001, 2003) and Jill Abramson (2011-2014).

Then you have Time, and Don Hank, saying:

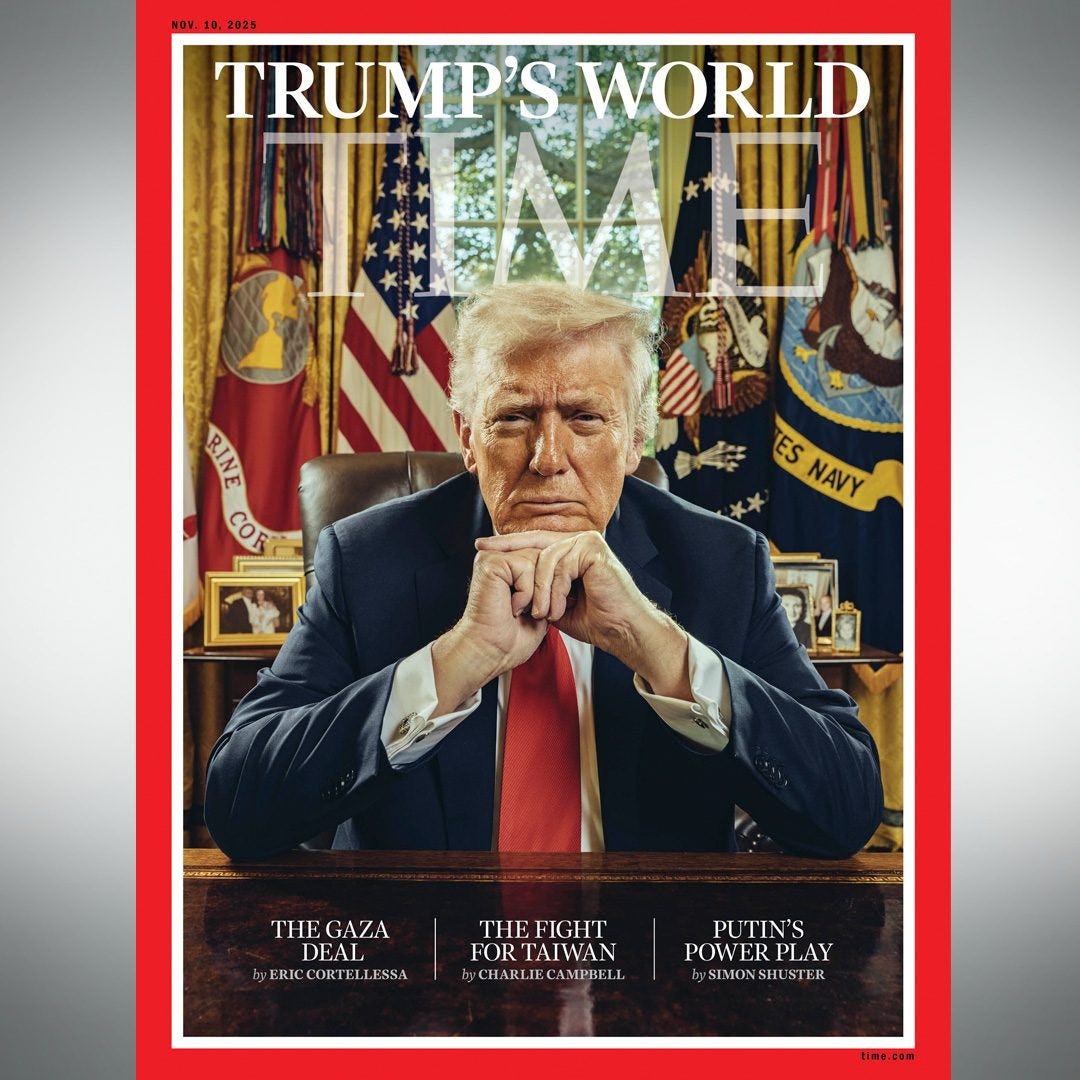

So, despite Trump’s shameless bragging, he has not stopped the war against Palestine, and then there are the Israeli bombings in Lebanon and Syria, which Trump will never address, at least not honestly.

The region is a shambles but Trump is pretending the war is over and is taking credit for it!

His other monstrous lie is that he has destroyed the Iranian nuclear program and put Iran out of business.

Even Time, which was respectful – but let’s be honest, it was obsequious with the old bullshit artist – admitted in a side bar that expert inspectors agree that Iran is NOT finished, and if you read the Iranian statements in their news sites and if you listen to real Iran experts like prof. Mohammad Marandi, you know they are quite capable of a devastating attack on Israel that would embarrass Trump and Netanyahu, and they are just biding their time. If they ever unleash their full missile power, there won’t be much left of Israel.

11. The journalist shall refrain from acting as an auxiliary of the police or other security services. [They] will only be required to provide information already published in a media outlet.

14. The journalist will not undertake any activity or engagement likely to put [their] independence in danger. [They] will, however, respect the methods of collection/dissemination of information that [they have] freely accepted, such as “off the record”, anonymity, or embargo, provided that these commitments are clear and unquestionable.1

This article provides evidence for the first time of a systematic policy of direct collusion between the Time Inc. media empire and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). For the first two decades of the Cold War, both Time and Life magazines established policies that provided the CIA with access to their foreign correspondents, their dispatches and research files, and their vast photographic archive that the magazines had accumulated to accompany their stories. These were significant resources for a fledgling intelligence agency. Photographs of foreign dignitaries, rebel groups, protestors, and topography were vital pieces of intelligence, helping the Agency to map and visualize its targets. Depending upon the story, direct access to dispatches returned by foreign correspondents might provide the Agency with important clues to local political, social, and economic conditions, as well as insights into the intentions and capabilities of ruling elites in countries of concern. Likewise, access to those foreign correspondents upon their return to the United States, whose whereabouts staff from Time Inc.—the parent company of the two magazines—routinely provided to the CIA, would allow the Agency to benefit from their insight and unique access to foreign lands, peoples, and leaders.

Hugh Wilford once wrote that during the Cold War it was sometimes “difficult to tell precisely where [Time and Life’s] overseas intelligence network ended, and the CIA’s began.” As Wilford and other historians have shown, a number of high profile Time Inc. journalists, including the company’s president, Henry Luce, maintained close contact with senior CIA officials, and even helped them with their propaganda efforts abroad.2 These studies have tended to emphasize the patriotic voluntarism of “Cold Warriors” in the U.S. media, like Luce, who were happy to help the U.S. government confront international communism.3 What until now has remained undocumented is the systematic cooperation between Time Inc. and the CIA for intelligence gathering purposes. When the magazines’ managers and editors became aware of a particularly interesting source, or network of sources, they would share it with the CIA. When journalists learned of major stories, their dispatches were sent directly to the CIA. When the CIA needed photographic intelligence, they often relied upon the photojournalism of Time Inc. When foreign correspondents returned to the United States, they would share what they had learned with the CIA. Indeed, it was difficult to tell apart the magazines’ sources of information from the CIA’s foreign intelligence network because, for a while at least, the former became part of the latter.

According to McCarthy, the agency established a modern PR office in the aftermath of “the Year of Intelligence,” a period between 1975 and 1976 when key intelligence agencies were being investigated for their abuses and wrongdoings. The investigation of the CIA included shocking revelations of illegal human experimentation under Operation MKULTRA, as well as the agency’s surveillance and wiretapping of American journalists and newsrooms, and its attempt to poison Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

David Atlee Phillips, a self-proclaimed “propagandist” for the CIA, was the face of many PR efforts in the 1970s, writing books and speaking at universities in an effort to counter the more negative, tell-all memoirs being published. These PR initiatives allowed the agency to try to craft an image of openness and transparency—just as it attempts to do in its new podcast.

“It’s always good to demystify this agency, given that there are still different public perceptions of this place that are shaped by films, books, and a ton of preconceived notions of what a ‘spy’ does,” says Bonnie, an analyst and public affairs officer at the CIA, in episode two of The Langley Files.

But what Bonnie fails to mention is that the agency has been working directly with Hollywood since its founding in order to shape that very image through film and television. In the 1990s, the agency launched an official entertainment liaison office to help assert its usefulness in a post-Cold War world and soften PR disasters. The CIA’s involvement can be seen in movies and shows like the film Zero Dark Thirty (whose filmmakers had unprecedented access to the agency’s files related to the killing of Osama bin Laden); the TV show The Americans (one of its creators, Joe Weisberg, is a former CIA agent, and the show’s scripts were subject to approval by the agency, lest Weisberg divulge still-classified information), and Homeland (which was a favorite at Langley).

It’s unclear why exactly the agency has decided that now is the time to move beyond film and TV and get into podcasting, though it could be a sign it’s looking to pique the interest of the next generation of recruits as it faces increased competition from companies like Amazon for talent. (One 30-year veteran of the agency, Kathleen, alludes to this possibility in the second episode of The Langley Files: “In order to attract and retain the workforce we need, to protect our nation, to stay one step ahead of our adversaries, we need to share a bit of what we do here,” she says, when asked why the public should be interested in the show.)

But whatever the reason for the CIA’s renewed PR push, it’s nothing new. The agency has more than 50 years of reliable PR strategies to choose from as it tries to polish its veneer of credibility as a trustworthy institution.

Throughout the 1984 press coverage of the Lebanon crisis, the press incessantly referred to the “Soviet-made” antiaircraft missiles and other arms possessed by the Syrians and Lebanese. But at no time were the Israeli arms described as “US-made” — which they were. The impression was that the Soviets were somehow the instigators in what was actually an Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

[…] Israeli authorities rounded up hundreds of Palestinian political leaders, administrators, teachers, journalists, intellectuals, and anyone else who might provide leadership to the Palestinian community, holding them in “administrative detention” for years on end, without charges. In effect, they were hostages to Israeli rule. But throughout 1991, the US news media invariably referred to them as “prisoners,” not hostages. Arab resistance groups, however, had no prisoners; they held only “hostages.” As of 1992, Israel held fifty-three UN personnel as hostages; almost all were Arab employees for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. The US media never labeled them as hostages. [1]

– Inventing Reality: The Politics of Mass Media, St. Martin’s Press Vintage (1986/2013), pp. 231–232

In a number of countries, such as South Africa, Zaire, Guatemala, Chile, Angola, and Haiti, where US policymakers have not always felt politically comfortable about committing American military personnel in noticeable numbers, Israel has been willing to do the dirty work in return for large sums of US aid and other special considerations. Likewise in countries such as Nicaragua (with the contras), El Salvador, Namibia, Taiwan, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bolivia, Israeli military personnel have worked as advisors in counterinsurgency. According to one Israeli writer: “Consider any third-world area that has been a trouble spot in the past 10 years and you will discover Israeli officers and weapons implicated in the conflict — supporting American interests and helping in what they call ‘the defense of the West.’” [2]

– The Sword and the Dollar: Imperialism, Revolution and the Arms Race, St. Martin’s Press (1989), pp. 55

The Soldier (1982). The Soviet KGB threatens to blow up half the western world’s petroleum supply with a nuclear device it planted in Saudi Arabia — unless the Israelis evacuate the West Bank in forty-eight hours. The Israelis refuse to budge. This upsets the U.S. president, who then decides to nuke the West Bank in order to vacate it and thereby save Western oil. The KGB are everywhere, having penetrated the highest reaches of the CIA itself. Luckily, a CIA counterterrorist team, who look like Young Republicans, side with the Israelis and refuse to knuckle under. They go in and kick Russkie ass. Moral of the story: Don’t be led around by the spineless politicians in Washington. (Better to be led around by the tough ones in Jerusalem and Langley, Virginia.) Give the Soviet aggressors the only thing they understand: a bullet in the belly and a gun butt in the face.

– Make-Believe Media: The Politics of Entertainment, St. Martin’s Press (1992), pp. 46

More recently, during the late 1960s into the 1970s, Israeli military officers were running drug shipments to Egypt, specifically targeting the Egyptian army. As one colonel said, “It allowed us to control and practically avoid drug smuggling into Israel, and increase the use of drugs within the Egyptian army.” Egyptian military officials admitted that during that period, drug consumption in the ranks rose by 50 percent {Covert Action Quarterly, Spring 1997).

– America Beseiged, City Lights Books (1998) pp. 133–134

In July 1993, the Israelis launched a saturation shelling of southern Lebanon, turning some three hundred thousand Muslims into refugees, in what had every appearance of being a policy of depopulation or “ethnic cleansing.”

– To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia, Verso (2000), pp. 12

By the same token we are not being anti-Semitic if we criticize the Israeli government for the incursions and settlements in the occupied territories and for mistreatment of Palestinians. Some of the most outspoken critics of Israeli policy are themselves Israelis in Israel or Jewish-Americans in the United States who — contrary to the facile psychologists charge made against them — are not “self-hating Jews.” In fact, most happen to be rightly proud of their Jewish heritage. Likewise, we are not showing hatred for Mexico, Italy, Poland, China, or any nation, nationality, or ethnic group if we denounce the particular policies of the Mexican, Italian, Polish, or Chinese governments.

– Superpatriotism, City Lights Books (2004), pp. 11

ISRAEL FIRST

The neoconservative officials in the Bush Jr. administration — Paul Wolfowitz, Douglas Feith, Elliot Abrams, Robert Kagan, Lewis Libby, Abram Shulsky, and others — were strong proponents of a militaristic and expansionist strain of Zionism linked closely to the right-wing Likud Party of Israel. With impressive cohesion these “neocons” played a determinant role in shaping U.S. Middle East policy. [3] In the early 1980s Wolfowitz and Feith were charged with passing classified documents to Israel. Instead of being charged with espionage, Feith temporarily lost his security clearance and Wolfowitz was untouched. The two continued to enjoy ascendant careers, becoming second and third in command at the Pentagon under Donald Rumsfeld.

For these right-wing Zionists, the war against Iraq was part of a larger campaign to serve the greater good of Israel. Saddam Hussein was Israel’s most consistent adversary in the Middle East, providing much political support to the Palestinian resistance. The neocons had been pushing for war with Iraq well before 9/11, assisted by the wellfinanced and powerful Israeli lobby, as well as by prominent members of Congress from both parties who obligingly treated U.S. and Israeli interests in the Middle East as inseparable. The Zionist neocons provided alarming reports about the threat to the United States posed by Saddam because of his weapons of mass destruction. At that same time, reports by both the CIA and the Mossad (Israeli intelligence) registered strong skepticism about the existence of such weapons in Iraq. [4]

The neocon goal has been Israeli expansion into all Palestinian territories and the emergence of Israel as the unchallengeable, perfectly secure, supreme power in the region.

This could best be accomplished by undoing the economies of pro-Palestinian states including Syria, Iran, Libya, Lebanon, and even Saudi Arabia. A most important step in that direction was the destruction of Iraq as a nation, including its military, civil service, police, universities, hospitals, utilities, professional class, and entire infrastructure, an Iraq torn with sectarian strife and left in shambles. [5]

– Contrary Notions: The Michael Parenti Reader, City Lights Books (2007) pp. 167–168

You see when the US planes come in, that’s called a raid. That’s not called a terrorist attack. People down there see it as a terrorist attack. It’s the same thing in Palestine. The Palestinians are terrorists because they use cars, and machine guns, and whatever else, and the Israelis are retaliating with jets and tanks. That’s seen as retaliation, that’s not seen as a terror attack, but it’s using terror too.

– Lecture, Globalization and Terrorism (2009)

Iran’s Islamic Republic has other features that did not sit well with the western imperialists. Iran was — and still is — a “dangerously” independent nation, unwilling to become a satellite to the U.S. global empire, unlike more compliant countries. Like Iraq under Saddam Hussein, Iran, with boundless audacity, gave every impression of wanting to use its land, labor, markets, and capital as it saw fit. Like Iraq — and Libya and Syria — Iran was committing the sin of economic nationalism. And like Iraq, Iran remained unwilling to establish cozy relations with Israel.

But this isn’t what we ordinary Americans are told. When talking to us, a different tact is taken by U.S. opinion-makers and policymakers. To strike enough fear into the public, our leaders tell us that, like Iraq, Iran “might” develop weapons of mass destruction. And like Iraq, Iran is lead by people who hate America and want to destroy us and Israel. And like Iraq, Iran “might” develop into a regional power leading other nations in the Middle East down the “Hate America” path. So our leaders conclude for us: it might be necessary to destroy Iran in an all-out aerial war.

– Article, Iran and Everything Else, michael-parenti.org (2012)

Still another reason for régime change in Iraq was concern for Israel. The neoconservative officials in the Bush Jr. administration — Paul Wolfowitz, Douglas Feith, Elliot Abrams, Robert Kagan, and others — were strong proponents of an expansionist strain of Zionism linked closely to the right-wing Likud Party of Israel. Assisted by the powerfully financed Israeli lobby, they pushed for war with Iraq well before the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center. [6]

Saddam Hussein was Israel’s most consistent adversary in the Middle East, providing political and financial support to the Palestinian resistance.

– The Face of Imperialism, Routlege (2016) pp. 108–109

The country that receives the bulk of US foreign aid is Israel, a nation that defies classification as either satellite or enemy of the US imperium. Israel imposes a continually repressive policy of land incursions and colonization upon the Palestinian population in Gaza and the West Bank without incurring any restraints from Washington. It is said that in the Middle East, Israel plays a subimperialism role to the United States, acting as a “stabilizing force,” a curb against revolutionary upheaval in the region. Debate continues among political writers as to whether it is the US or Israel that has the upper hand on Middle East policy. To be sure, with its well-financed Zionist lobbies and big-moneyed contributions to both Republicans and Democrats — unmatched by anything the anti-Zionists can muster — Israel exercises a most impressive influence over US policy in the region, an influence that extends into Congress, the State Department, and the White House itself, regardless of which party is in charge. [7]

– Ibid., pp. 126

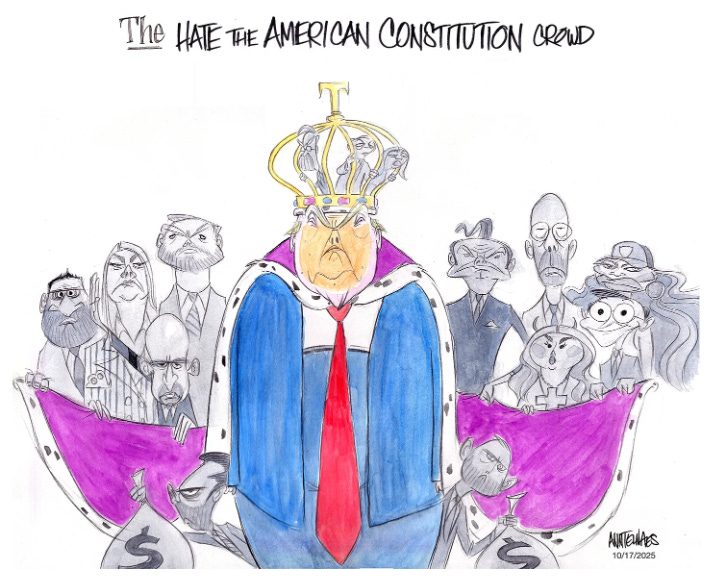

Nothing you will see at a No Kings Teletubby protest:

“Under fire, the children, the elderly, the mothers of Donbass—they all deserve to be heard”

Zhu Haozheng, a Chinese journalist and war correspondent, speaks about life in Donbass under Ukrainian fire.

The most striking memory is the first few days after the liberation of Avdeyevka. My crew and I were among the first journalists to arrive there. Drones circled overhead, and our air raid sirens blared incessantly. The city outside the car window was practically a ruin—not a single house remained intact, and the air was thick with the smell of burning. We risked our lives filming footage and released it in collaboration with the Chinese-language service of the Russian Satellite News Agency. The video subsequently garnered approximately 500,000 views on Chinese social media, a true success for me.

Later, I visited a monastery near Ugledar. They were the most resilient people I had ever met—dozens of residents living in the monastery’s basement, without water, electricity, or signal. They survived on a small supply of canned food and water brought in by volunteers, along with gasoline generators. At that moment, I realized that journalism isn’t just about reporting on artillery fire; it’s about documenting human nature.

This year, I visited the Kursk border region again. Although it had been liberated, the sound of drones could still be heard. Drones have become a near-mainstay of warfare—reconnaissance, strikes, and psychological deterrence—everything is carried out by them. But I also see hope for reconstruction: in Mariupol and Lugansk, people are rebuilding their houses and opening shops.

I love Donbass. I’ve lived in Donetsk for two years now. Despite enduring so much hardship, the people here maintain their kindness and dignity. I’m studying for a master’s degree in journalism at Donetsk State University. My Russian isn’t very advanced, but my teachers and classmates are very patient in helping me.

One of the biggest challenges facing Donetsk is the water supply. In theory, water is delivered every three days, but in reality, sometimes it goes all week without any. For example, this past September, my neighborhood only received water four times. Most of the time, I have to carry buckets to the makeshift water tank on the street corner to fetch water. Many of the residents here are retired, and life is very difficult for them, so I often help my neighbors fetch water and deliver food. I also try to raise some humanitarian aid—mainly food, drinking water, and medicine—through my Chinese friends. While my contribution may be limited, I hope to let people know that Donbass has not been forgotten.

[Question: Have you come across the PFM-1 mines which Ukraine has fired onto Donbass cities repeatedly since 2022? If so, where and was anyone injured by them?]

These small mines are extremely dangerous. They look like toys and could easily be mishandled by children. I first saw them in the Kuibyshevsky district of Donetsk, an area that experienced intense fighting, and unexploded ordnance can still be found on the ground. The Donetsk Military Investigative Committee has collected numerous defused PFM-1 mines as evidence of Ukrainian use of banned weapons. I saw their display, where the small green mines were neatly arranged on metal racks. Looking at them, you truly feel the cruelty of war.

[Question: Have you met any Ukrainian soldiers who surrendered? If so, what did they tell you was the reason they surrendered? How did they say they are being treated by Russians?]

I spoke with Ukrainian prisoners remotely. Their stories were shocking. They said they had no desire to fight—they were grabbed by conscription officers, put on buses, and forced into the army. Some were threatened with charges and imprisonment if they refused to serve. When Russian troops approached, they surrendered. They told me that the Russian soldiers didn’t mistreat them; instead, they were provided with water, food, and a place to sleep.

[Question: Have you had any negative feedback in your reporting, from Western or Ukrainian media or other?]

Of course. This is especially true in Chinese online spaces. Roughly half of the Chinese population supports Russia, and the other half supports Ukraine. Some accuse me of “propaganda for Putin” and even call me an “accomplice of the invaders.” They fabricate online rumors, claiming I’m using rubles to fabricate reports.

I’ve investigated the accounts of some of these attackers, and their IP addresses appear to be located in the US, UK, Germany, and even Ukraine. They constantly talk about “liberal values,” yet they express extreme hostility toward alternative voices. To me, this demonstrates that even so-called “freedom of speech” is selective.

However, this won’t stop me from reporting. Because in Donbass, I see a different reality—not the narrative shaped by the media, but the lives of individuals who have lived through blood and tears.

I’ve always been honored to tell the heroic stories of our time, despite the difficult times we face. I record the truth as I see it. Regardless of one’s perspective, everyone should know: Under fire, there are always people struggling to survive. The children, the elderly, the mothers of Donbass—they all deserve to be heard.”

Trump Is Every Day. the Resistance Is Every Few Months. Wonder Why He’s Winning?

Hundreds of thousands of anti-Trump “No Kings” demonstrators marched on Saturday through the streets of thousands of American cities, to expose general opposition to the ruling Republican Party and to express outrage over their various policies.

Like its predecessors, this effort will have zero effect.

Performative protests like “No Kings,” the 2017 Women’s March and the Hands Off marches this past April — organized by Democratic Party affiliates and allies — cannot accomplish meaningful change because they do not exert political pressure. Because they are nonviolent to the point of self-policing would-be militants in their midst and, occurring on weekends when most businesses and government offices are closed and therefore nondisruptive, the crowds pose no threat to the rich and powerful or their pet politicians.

Donald Trump and MAGA world are every day. They work tirelessly to push their radical right agenda. “No Kings” and likeminded exercises in safe, sanitized street displays (“in many places, the events looked more like a street party”) meet once every two or three months and thus fail the first test of agitation, which is to create chaos sustained and predictable enough to feel at least a little dangerous.

The last time this country saw a level of agitation big enough to make the ruling class worry was during the Vietnam War. There were huge marches in cities like New York and Washington. But what really helped shift the views of fence-sitting moderates was the ubiquity and consistency of the antiwar movement. Every morning, my mom drove me to school past a half-dozen anti-Nixon folks holding signs on the median strip along Route 48 south of Dayton, Ohio. Whenever we drove by the entrance to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, there were 20 or 30 lefties and hippies shouting slogans. They were there morning, noon and night, through rain, sleet and snow. No matter what you thought of them or the war, you couldn’t help but be impressed by their commitment and resolve.

No one thinks those who show up for “No Kings” are brave. It is neither sustained nor ubiquitous. Nor is “No Kings” a movement. Building a movement requires a broad-based grassroots opposition organization that is independent of the two main parties permitted to participate in U.S. electoral politics. There is no such group or party.

“No Kings” is barely even a protest. Against what? Kings? There is no danger of monarchy. The threat today is authoritarianism. Against Trumpism? Trump and Joe Biden — whom these same people never protested because he was a Democrat — were identical on the big issues: the genocide in Gaza, the minimum wage, health care. Protests have demands: Stop the war, raise wages, let us vote. “No Kings” issued no demands. Just a request: Show up and have fun.

In his landmark speech delivered to the first Tricontinental Conference of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America held in Havana in January, 1966, Amilcar Cabral appealed to attendees,

“We are not going to use this platform to rail against imperialism. An African saying very common in our country says: “When your house is burning, it’s no use beating the tom-toms.” He continued, “On a Tricontinental level, this means that we are not going to eliminate imperialism by shouting insults against it.”

Last weekend a series of events across the United States branded as “No Kings” developed by the 50501 group (vis a vis Indivisible) garnered an estimated seven million attendees. While it’s clear that the events provided many who participated with opportunities to enjoy an acute catharsis as evidenced by pithy signage and costumes and makeshift instruments to accompany marches on streets with the permission of the State through the purchase of permits, many are questioning the overarching futility of one day of “action” that provided no concrete demands save that President Trump stop hurting people and communities with his draconian policies and provocative, incendiary rhetoric aimed at his political opponents and those in the country he deems are “un American.” In sum, a growing chorus of people are wondering if we are merely beating our tom-toms or building collective power at scale to beat back interlinked injustices pronounced by rising militarism, rising emissions, and rising white “supremacy.”

Fuck MAX and his KLAN:

As of late 2025, Sidney Blumenthal is active as a political columnist for The Guardian and a presidential historian. He continues to write and speak about American politics, particularly concerning the Trump administration.

Recent activities

- Columnist for The Guardian: Blumenthal writes columns analyzing U.S. politics for The Guardian. An article was published as recently as October 24, 2025, discussing what he calls a “regime of retribution and reward” during the Trump administration. He formally joined Guardian US as a regular columnist in September 2023.

- Author of Abraham Lincoln biography: He is the author of The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, a multi-volume biography. The third volume, All the Powers of Earth, was published in 2019.

- Historian and speaker: On August 8, 2025, he was a featured speaker at a virtual event for Brandeis University alumni. His talk covered the first six months of Donald Trump’s second term and its implications for the future of the United States. In June 2025, he was a guest on the radio program Background Briefing to discuss the political situation in the Middle East.

- Political commentator: In August 2025, he was interviewed by German publication The Pioneer regarding the political climate in the U.S. under the Trump administration.

Background

Blumenthal’s career spans several decades as a journalist, political adviser, and author.

- He served as a senior adviser to President Bill Clinton from 1997 to 2001.

- He was a longtime confidant of Hillary Clinton and served as an adviser on her 2008 presidential campaign.

- He is a prolific author, with other notable works including the memoir The Clinton Wars (2003).

- He previously worked for publications such as The New Republic, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker.

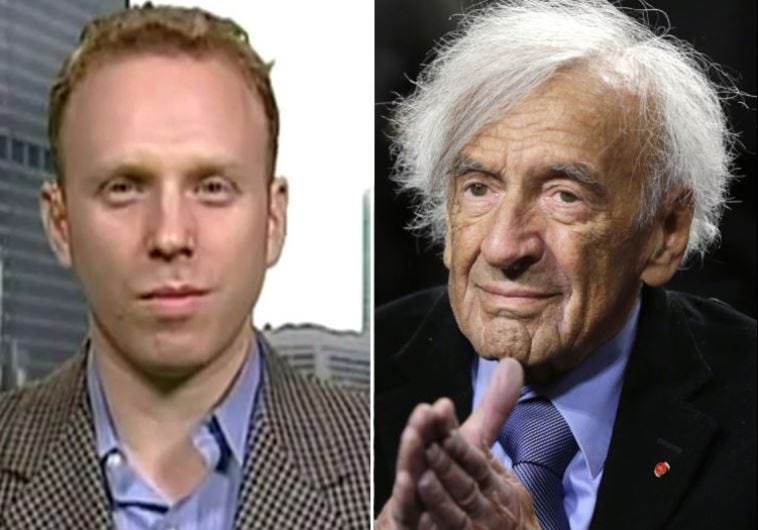

Faggot MAX: I’ll ask your audience: ‘Do you AGREE WITH YOUR PARENTS ON EVERYTHING?

This is the fucking Jewish deal, man, through and through.

Following a barrage of angry comments he received for responding to the passing of Elie Wiesel by vilifying the Nobel Prize laureate, the son of Hillary Clinton’s close confidant Sidney Blumenthal doubled down on his vitriol, while the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee hastened to distance herself from it.

Hillary Clinton “emphatically rejects [Max Blumenthal’s] offensive, hateful and patently absurd statements,” her campaign’s senior policy adviser, Jake Sullivan, said on Tuesday. “She believes they are wrong in all senses of the term. She believes that Max Blumenthal and others should cease and desist in making them. Elie Wiesel was a hero to her as he was to so many, and she will keep doing everything she can to honor his memory and to carry his message forward.”

On behalf of his boss, Sullivan was referring to a series of hostile tweets that journalist Max Blumenthal posted on Sunday, the day after Wiesel’s death. As The Algemeiner reported, Blumenthal — senior writer for AlterNet and author of Goliath and The 51 Day War: Ruin and Resistance in Gaza, a virulently anti-Israel book about Operation Protective Edge in the summer of 2014 — said that Wiesel

“did more harm than good and should not be honored;” that he “went from a victim of war crimes to a supporter of those who commit them;” and that he “repeatedly lauded Jewish settlers for ethnically cleansing Palestinians in East Jerusalem.”

JEWS:

What’s up with this headline?

Why Trump is bailing out Argentina’s libertarian leader Javier Milei with $40 billion

The Donald Trump administration is using $20 billion of US government money plus $20B more in private loans to bail out Argentina’s corrupt libertarian President Javier Milei, meddling in its election

Libertarian? FUCK. FASCISTS:

Trump has bet a lot on Milei. The right-wing Argentine president is one of Trump’s closest allies on Earth. They have a lot of similarities. Like Trump, Milei won the election by cynically portraying himself as a “populist”, even though he chose the rich banker Luis Caputo to serve as his powerful finance minister, after he made a fortune trading stocks for the Wall Street mega-bank JPMorgan.

Trump and Milei have also both carried out similar corrupt schemes. Like the US president with his shady Trump coin, Milei scandalously promoted a meme coin rug pull that caused his own supporters to lose billions of dollars, in what became the biggest ever crypto theft.

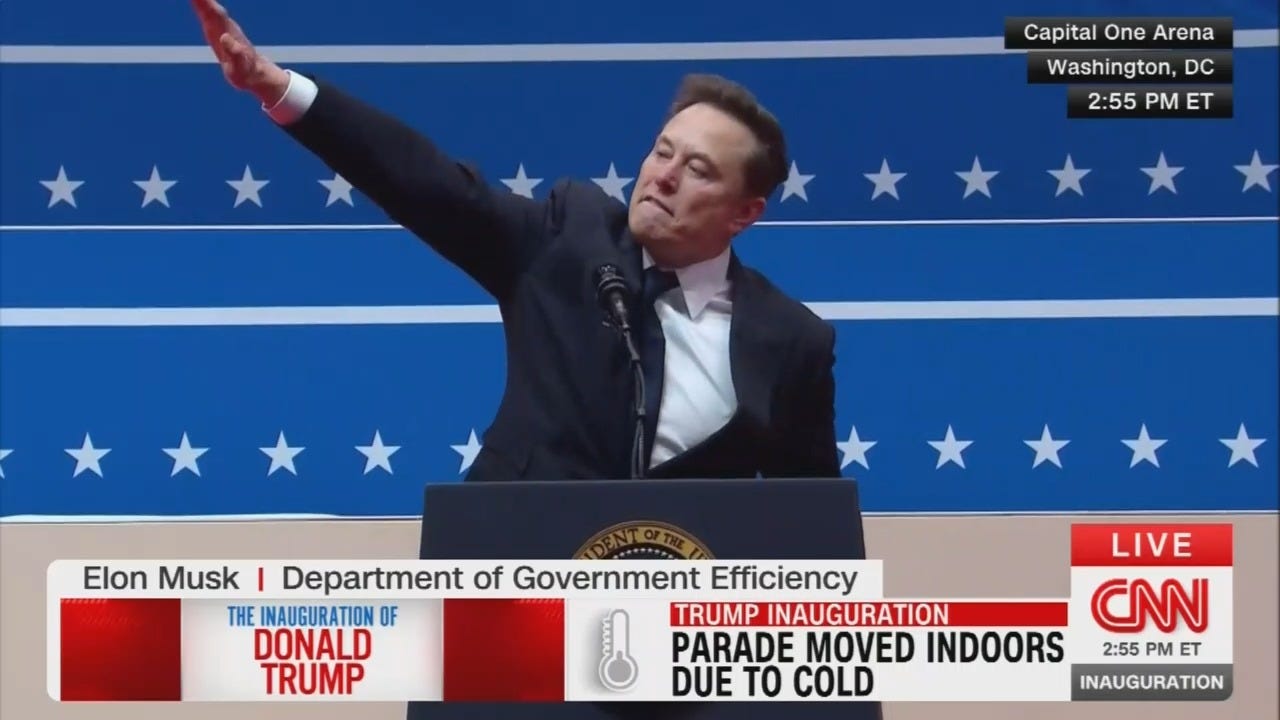

Milei is likewise very close to the world’s richest man, the centibillionaire Elon Musk. In fact, Milei inspired Musk to launch his failed Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. And when Trump signed an executive order vowing to dismantle the Department of Education, he was echoing Milei.

It’s important to note as well that Elon Musk has a vested economic interest in Argentina. The electric cars made by his company Tesla need lots of lithium for their batteries, and Argentina just so happens to have some of the largest lithium reserves on Earth.

As authors Liz Theoharis and Noam Sandweiss-Back discuss in their latest book, You Only Get What You’re Organized to Take,

“…many of this country’s most significant, positive social changes have emerged from the bottom of society, with ripple effects that have ultimately yielded broad social benefits.” They go on to say, “This kind of progress is never linear or promised – it is demanded by those who for their very survival, are first compelled to take transformative action.”

- Douglas Emhoff: As a successful entertainment lawyer, he earned over $1 million annually in 2019 before he left his law firm in 2020 to take on the Second Gentleman role. He is now a law professor at Georgetown University.

- Kamala Harris: She has received more than $500,000 in book royalties from titles including her memoir, The Truths We Hold, and the children’s book Superheroes Are Everywhere.

- Pensions: Harris has accrued pensions from her many years in public service in California, which Forbes estimates are worth just under $1 million

Doug Emhoff and California governor Gavin Newsom went vinyl shopping in Philly before the presidential debate, the latest example of the Harris-Walz campaign’s music geekdom

And so here we are, broken down Yankees and Gray Coats, Nazis and Birkenstock hippies, Subaru’s and F-150 pick-ups, good vibrations or white claw, hot yoga and hot wet t-shirt contests, America, the land of Fulfillment Centers/Warehouses for those fucking brunches and duck hunts:

A tale of two peoples?

And so the Iberians, the COnquistadors, here we are in Columbia:

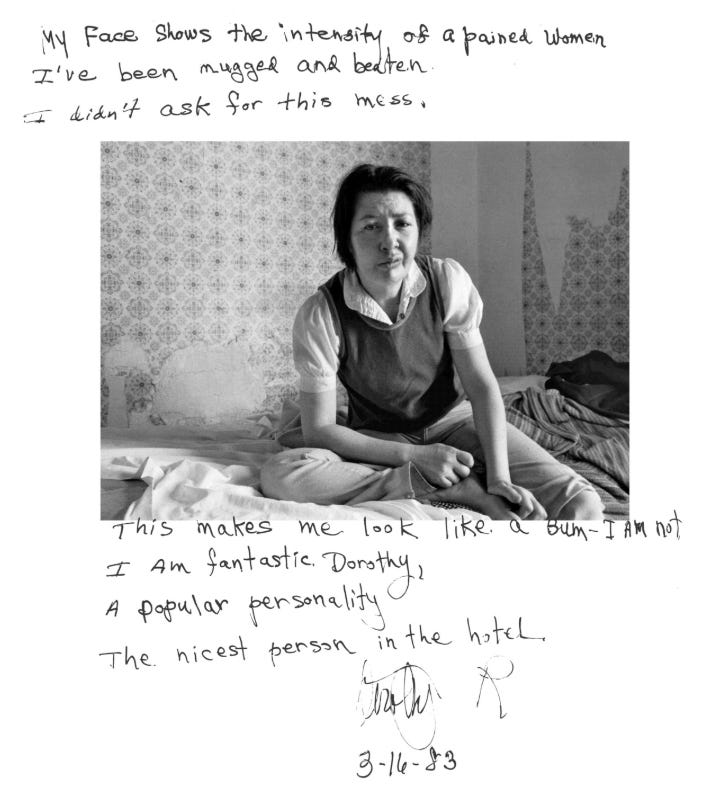

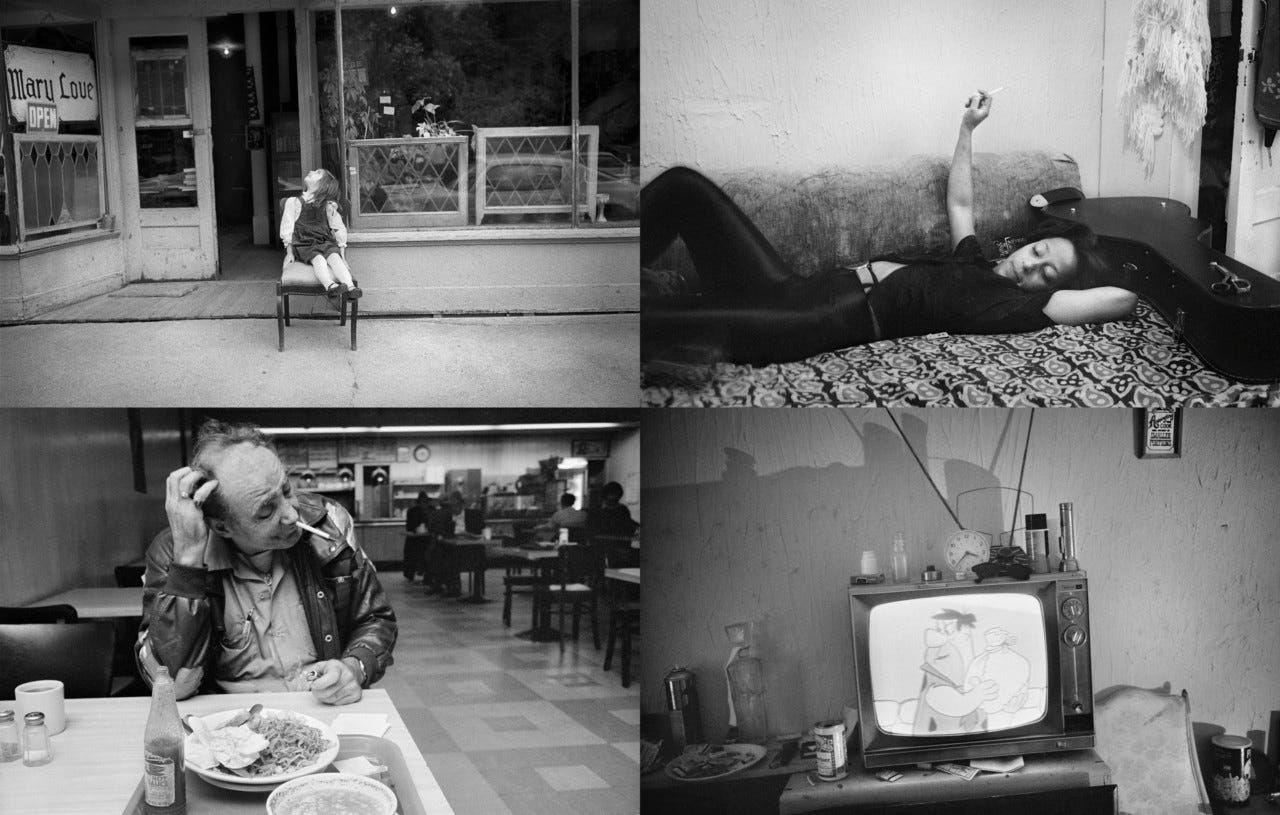

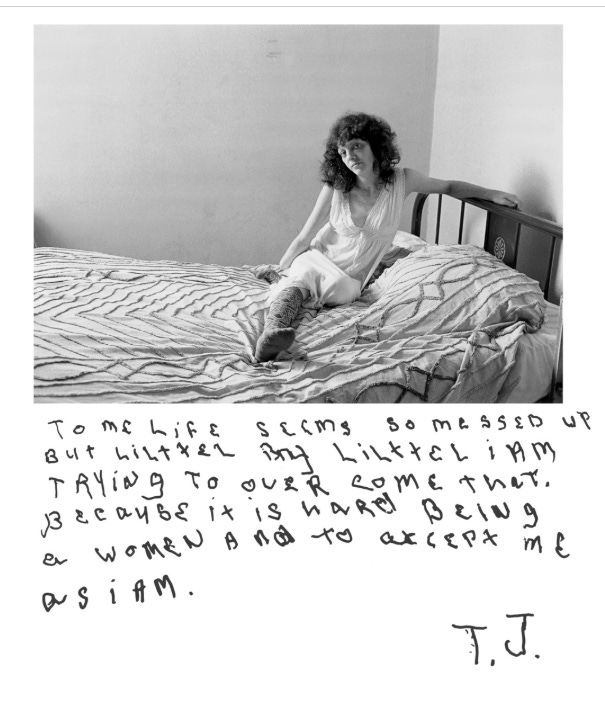

“I can’t let go of the desire to believe in a society where things really will get better” — Jim Goldberg on his seminal work documenting the “Rich and Poor” of San Francisco

Rich and Poor People—fiction by Farah Ahamed

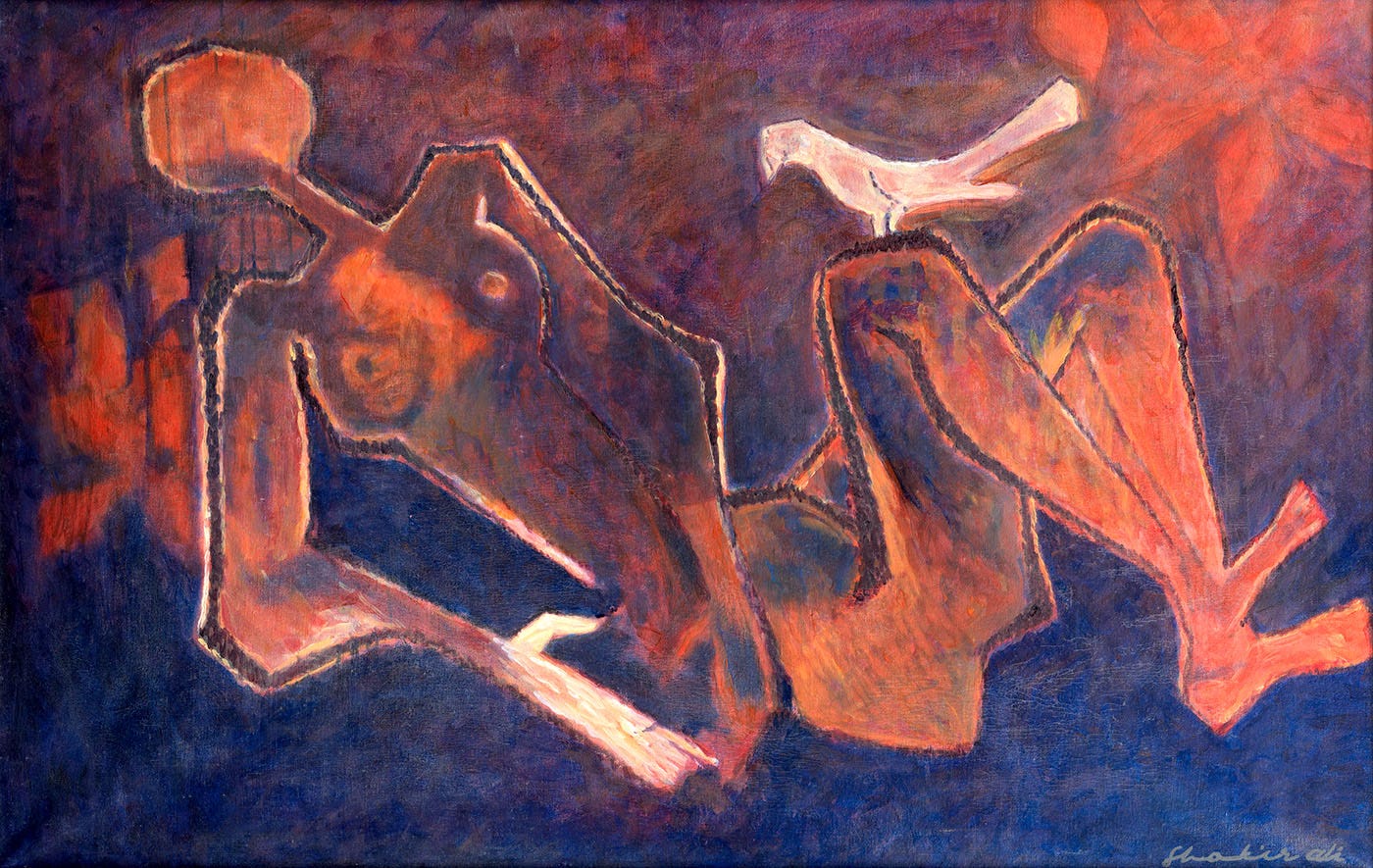

FN Souza (1924-2002), Untitled, oil on board 120×181.3 cm, 1958 (courtesy Sotheby’s).

I’m going to give them a piece of my mind. Who do they think they are, feeding the crows KFC chicken?

Rich people have no idea what it’s like to be poor.

When you’re poor, you’re used to people dropping dead like flies and spending half your salary every month on funerals. Being poor means you’ll die young, because if you’re ill, you won’t have a car to take you to the hospital. And if by some luck you get there by bus, you’ll have to sit on the cold floor in the hospital corridor and wait for hours. And when the nurse finally takes you in, there’ll be no bed, medicine, or doctor. If you survive, your baby might die. If you hit your chest and cry, everyone will say it was God’s will, and if He took away your child, maybe one day He’ll give you a chance to change your destiny and know what it’s like to live like the rich.

Rich people have the luxury to mourn. They make a fuss about every death as if it were not a daily occurrence. Take Ma’am Farida and Mr. Abdul. I’ve been working for them for twelve years now. Last month Mr. Abdul died of a heart attack, and now Ma’am Farida is heartbroken. Every morning she opens the sliding doors to the balcony and looks at the apartment directly across the way. If you asked her why she was so interested in the neighbors, she’d tell you she didn’t care about them — it was what they were feeding the crows that bothered her. That’s another trait of the rich: They’re not interested in the poor, but more worried about the birds starving.

Farida likes to look at those crows in the balcony opposite. The people living in that apartment are new to the building. They like to feed the crows. You’d think rich people like them would buy proper bird feed, but no, they don’t like to waste money on such things. They give the birds their leftovers, and Farida watches the black birds pecking at food in the foil containers and becomes very angry. This morning she swore she’d seen a crow with a bone in its beak, which it had taken from a red and white KFC box on the neighbor’s balcony ledge.

“What are they doing, giving fried chicken to the crows?” she said to me.

I couldn’t tell her “rich people are like that, thoughtless,” so I just said, “Yes, Ma’am.” I busied myself with wiping the mugs in the cabinet printed with congratulations you’re retired now, which Mr. Abdul had received from the university a few years ago. He’d never let Farida use them.

“Abdul would have been appalled,” Farida said. “Don’t you remember how he used to feed the birds with special seeds and watch them feast?”

Mr. Abdul was very particular about the birds, and he had his reasons. Every morning at breakfast he’d call Farida to come and watch the crows. “See how they’re family-oriented,” he’d say. “See how their behavior is so civilized. They could teach you a thing or two, Farida.”

“What do you mean?” she’d say. “Crows are mean and vicious. What’s there to learn?”

One thing you should know about Mr. Abdul is that is he didn’t like being challenged, and over many years I’d observed how he’d controlled Farida.

“The problem with you, Farida,” he said, “is that you don’t look.”

“Those birds are nothing but pests,” she said.

“I’d watch my tongue if I were you,” he said. “If they hear you, they’ll come after you for revenge.”

It makes me want to laugh, how rich people quarrel about meaningless things. When you’re poor you fight about bills, and how your husband is wasting money on gambling and alcohol. You’re at each other’s throats all the time, because what else is there to do? There’s no time for anything but work. No time to put your feet up and have a cup of tea. And here they were, Farida and Mr. Abdul, fighting over the mannerisms of crows.

Every day, it was the same. At first it was amusing, but as Mr. Abdul became obsessive about his birdwatching, their arguments became more heated. What irritated Farida most was the way Mr. Abdul compared her to the crows.

“Crows are sharper than you, Farida,” he said. “They recognize faces.”

“Nonsense,” she said. “Just like all crows are the same for us, all humans are the same to them.”

“Your worst habit is that you never want to accept facts.” And he carried on pointing out more positive characteristics about the birds. “Trust me, Farida, once a crow knows your face, they’ll never forget it.”

Finally, Farida said, “Please stop, I couldn’t care less whether they know me or they don’t. It makes no difference to me.”

And because Mr. Abdul always needed to have the last word, he said, “Well you should, because crows hold grudges.”

Maybe now that Mr. Abdul was dead, Farida was asking herself if it was true what he had said; were the crows more intelligent than her? There she was, standing on the balcony, all alone, thinking the crows were all she had left. And she was crying.

“There, there,” I said, and tried to lead her into the sitting room, where I’d kept her breakfast on a tray. “Have some tea. It’s getting cold.”

But she pulled her arm away. “Not now. Can’t you see I’m busy?” She kept her eyes fixed on the black birds jabbing at the KFC box. One cocked its head in her direction and gave a loud croak. Farida gave a small shudder. “Don’t the neighbors care the birds will get indigestion from eating fried chicken?”

“No, Ma’am,” I said, and then before I could stop myself, I blurted out, “Rich people don’t worry about things like that.”

She ignored my comment. “Abdul suffered from terrible heartburn,” she said. “He was very sensitive.”

“Yes, Ma’am.”

“He’d always say, “‘My nerves and stomach are connected,’ then gulp down the ENO while it was still fizzing.”

She looked like she was about to start crying again, so I said, “Please, Ma’am, Mr. Abdul would have liked you to eat your breakfast.”

“How would you know what he wanted?” she said, irritated.

“I haven’t been with you for 12 years for nothing, Ma’am.”

She turned to look at the stool, and I saw her taking in the tea spilled in the saucer, the burned omelet and over-browned toast. Mr. Abdul would never have tolerated me serving such a sloppy breakfast. But he wasn’t there to shout anymore, so I didn’t bother being tidy.

“Leave the tray there,” she said, and returned to watching the birds.

Another characteristic of the rich is they like to waste food. Mr. Abdul always wanted fresh rotis for his lunch, and when I’d bring him a hot one from the kitchen, he’d stop eating the one he’d just taken a bite of and leave it aside, saying it was cold. I started collecting his half-eaten rotis to take home. I’d shave off the edges, cut them into small pieces and keep them in a box. At the end of the week I’d make a dry curry from the leftovers, with tomatoes and onions. This is one way in which the poor survive.

People die in their sleep all the time. When you’re poor you accept it and carry on. But rich people insist on making a fuss. It was true that Mr. Abdul had died suddenly; one minute he’d been fast asleep beside Farida, and the next, when she’d tried to wake him, she’d found he was dead. After the funeral, her daughters had said she should take turns living with them, and suggested a rota. But Farida had refused.

“I’m not an old suitcase,” she said. “I won’t be carted around from one place to another, until my wheels fall off. I’m not going anywhere. I’ll stay here with Mary.” So her daughters returned to their lives, and she was left here with me.

Mr. Abdul had often told Farida she was incapable of living on her own. He said, “You’re not the independent type, Farida, you wouldn’t know where to begin.”

She hadn’t bothered to contradict him. Maybe she couldn’t imagine her life without him.

I can tell it is noon by the way the sun falls at a particular angle on the parquet floor. Mr. Abdul was very particular, and insisted I scrubbed the floors once a week with a special gloss polish. But nowadays, because he’s not there to notice, and it is such an effort, I don’t bother.

I watched Farida pulling the rocking chair into the patch of light, and sitting down, she shut her eyes. I imagined her enjoying the warmth of the sun on her face. When you’re poor, you don’t have time to enjoy anything.

Mr. Abdul and Farida have lived in this campus flat for the past 30 years. They’d moved to Lahore when Mr. Abdul had joined the School of Engineering at the university. Their flat is on the fourth floor in the middle block of six buildings with identical architecture, arranged fifty feet apart. The tinted-glass windows lend some privacy, but like everywhere else on the campus, the buildings are packed close together; you can look straight into the balconies opposite and see the broken suitcases, old mattresses, dead plants, and washing lines with faded clothes.

One night, when I was clearing the table after dinner, Mr. Abdul began checking the windows as was his habit before bed, when he noticed one of the neighbors reversing their car into his parking area. He immediately rang them up and asked them to remove it.

“You’re being unreasonable,” the neighbor said. “You don’t have a car, and the spot is free, so what’s the problem?”

“It’s my space, so I’ll decide — and right now I want it empty,” Mr. Abdul said, and then he hung up.

Farida said he ought to be more patient.

“Never,” Mr. Abdul said. “If you don’t react right away, they’ll take you for a fool and do it again.”

Mr. Abdul took the matter to the Housing Management Committee and demanded a written apology from the neighbor. The Chairman said no harm had been done, and that Mr. Abdul ought to be a little more flexible. But Mr. Abdul wasn’t having it.

“Don’t interfere with matters which you don’t understand,” he said when Farida tried to persuade him. “It’s a matter of principle.”

The rich think they have the gift of reading people’s minds, and Mr. Abdul especially was of that opinion. Poor Farida, not once had Mr. Abdul seen things from her point of view. She’d fought back as much as she could, but he’d never conceded. Maybe the overwhelming sense of defeat, after his passing, was part of her sorrow.

Later that afternoon, when I saw Farida lying on the sofa with her eyes closed, I went down to the garden. Haroon was waiting for me, and we sat together in the cool shade of the amaltas. However, only after a few minutes I heard Farida calling my name.

“She’s a bloody nuisance,” I said to Haroon. “Look, she’s watching us from the balcony.”

“Mary, get back here at once,” Farida shouted. “What are you doing?”

I raised my arm and waved, and stayed where I was. I gave Haroon the Tupperware container that I’d sneaked out of the kitchen in the folds of my apron. He stroked my cheek, took out a chocolate-covered barfi and popped it in my mouth. These chocolate sweetmeats were Farida’s favorite.

Haroon and I’ve been together for five years. He works as a gardener on the campus. Last year, we lost a baby. We’re trying to save so we can get married. Haroon’s not the most handsome man you’ll ever meet, but he’s got a good heart. He’s thin and dark and always wears a faded red scarf tied like a turban to protect his head from the sun. It makes him look like a man who’s been walking for miles in the desert. Sometimes he drinks too much liquor, and then we argue.

Farida was still standing in the balcony looking at us. “Did you hear what I said, Mary? Get back here,” she shouted.

I lay my head on Haroon’s shoulder; he smelled of cut grass, and sweat. “Happy Birthday, my love,” he said.

“Oi!” Farida called.

“I’m coming, I’m coming,” I said, but made no effort to get up. I knew my reply would infuriate her, and she’d think I was being cheeky. Over the years I’d often heard Mr. Abdul saying, Never trust the servants, they’ve no loyalty. Always keep them in line, or they’ll end up sitting on your head.

I hate admitting it, but on and off Farida has tried to help me. One time she gave me her old clothes and shoes and her favorite orange handbag, but that was only because the strap was broken. “Make sure you look after it,” she had said. And whenever she’d see me carrying it (because I got it repaired), she’d comment how nice it looked, and I could see she regretted giving it to me. However, I didn’t offer to give it back. Instead I told her how many compliments I’d received.

“Just don’t let Abdul see you with it,” she said. “He’ll say I’m spoiling you.”

We both knew Mr. Abdul had the smallest heart in the world, but our shared understanding of him did not make Farida and me any closer.

Last year, when I was pregnant, I asked Mr. Abdul for a loan so I could get some medical treatment.

“Do I look like a charity to you?” he said. “Why don’t you ask your church to help?”

Farida tried telling him that I’d been feeling unwell and that I was expecting a child, and why couldn’t he deduct a small amount from my salary every month? But he refused. “Haven’t you learned, Farida, that you should never get soft with servants? If you do, they’ll only manipulate you.”

Rich people think they have the gift of prophecy.

When I was back from the garden I went straight into the living room. “You called me, Ma’am?” I said.

“What were you doing with that man?” she said. “Who is he?”

“Haroon’s my friend, Ma’am.”

“Friends? Since when do you have time for friends?” She took her dupatta from the chair and flung it around her shoulders. “Abdul wouldn’t have allowed it.”

I raised my chin and looked directly at her. “But Mr. Abdul’s not here, is he?”

“How dare you? I’m going to give that gardener a piece of my mind.”

“Please Ma’am, we were just talking.”

“I don’t trust you,” she said. “I saw you giving him something. What did you steal? I’m going to find out and end this nonsense, right now.” She hobbled to the front door and I followed her out and down the stairs.

“Be careful,” I said. “We don’t want you to have another fall, Ma’am.”

“I didn’t ask for your opinion,” she said, going down the stairs sideways and holding the railing for support. We reached the ground floor, where we saw Haroon raking the yellow flowers under the tree.

“Oi!” Farida raised her arm and beckoned him. He stopped sweeping and came over. “I don’t pay Mary to gossip with you,” she said. “So don’t talk to her.”

“Today’s her birthday, Ma’am,” he said smiling at me.

“What nonsense,” she said. “Today it’s hers, tomorrow it’s yours, and the day after it’s something else.”

Haroon took the Tupperware from his pocket and offered it to her. “Please try some chocolate barfi, ma’am.”

“What nerve,” she said, her facing turning red. “I recognize those barfis from my kitchen. How dare Mary take them without my permission?”

Just then there was a strong gust of wind, and an empty KFC carton came sailing down towards us. It landed a few feet away from where we were standing, scattering chunks of chicken and chips everywhere.

“This is the limit,” Farida said, and shading her eyes with her hand, she squinted up at the neighbor’s balcony. “Enough is enough.” She began limping towards the opposite building, as a crow flew down and started pecking at the food. “I’m going to give them a piece of my mind. Who do they think they are, feeding the crows KFC chicken?”

“Ma’am,” I said. “Wait.”

“I haven’t finished with you yet, Mary,” she said. “I want to know exactly when you started stealing.” She mumbled as she climbed the stairs using the railing. “Stealing … lying … cheating … Abdul warned me never to trust the servants …”

I went after her, and Haroon followed. “Go away,” she wheezed. “Leave me alone.” We did not respond, but stood behind her in case she lost her balance, watching as she mounted the second and third flights of stairs. “Abdul always said if you can’t defend your principles, you’re worth nothing,” she said.

“Yes, Ma’am. But he’s gone, so it doesn’t matter anymore.”

“Be quiet, I know what I’m doing.”

Poor Farida. She was losing her marbles. It is no big deal, people are losing things all the time. When you’re poor, you forget things on the bus, or someone picks your pocket or snatches your purse. These things happen every day. But it’s different for rich people; they can’t stand it when something gets lost.

A few years ago Mr. Abdul’s watch had gone missing. “Someone’s stolen it,” he said to Farida.

“It could have fallen off your wrist,” she said. “The strap was loose. You must have misplaced it somewhere …”

“I’d have known if that had happened. I’m not as careless as you are,” he snapped. “Thieves are always looking, and watching. They have a thousand eyes, and when you least expect it, they’ll pounce.”

Mr. Abdul made me search the entire apartment, but the watch didn’t surface. He went through every hour of the day he’d lost it, where he’d been and who he’d met, and became more convinced. “I’ve been robbed,” he said. “Violated in broad daylight.” He gave me long, brooding suspicious stares, but I just looked back at him.

Farida had grown tired of his moaning about the watch. “For my sake, just get a new one,” she said.

“This city is full of thieves. When they see a soft target, they attack.”

“Forget about it,” Farida said. “There’s nothing we can do about it now.”

“No, I’m not letting them get away with it.” Mr. Abdul sat down again in his usual chair and went through the events of the day all over again. But he remembered nothing different.

A few days after the watch incident, Haroon knocked at the door, accompanied by a man. Haroon said the man had something to show Mr. Abdul. The man, a casual laborer working at a building site, opened his handkerchief, which was tied with in knot. “I’m selling this watch,” the man said. “If you like it, you can buy it.”

“Where did you find it?” Mr. Abdul snatched it from the handkerchief and fastened it around his wrist. “How dare you? First you steal it, and now you want to sell it back to me?”

All the trouble that Haroon and I had gone through came to nothing. We didn’t make a single rupee, because Mr. Abdul refused to buy back his watch. “Never,” he said to Farida. “If I do, every morning something will go missing from this place, and every evening we’ll have a thief trying to sell it back to us.”

“The man must’ve found it somewhere,” Farida said. “All you had to do was give him a small reward.”

“Don’t underestimate poor people,” he replied. “For them it’s all about survival.”

When we reached the fourth floor, Farida leaned against the wall and fanned her face with her dupatta. She looked at the three doors. “Where do the culprits live?”

I pointed to the middle door, and she limped across and knocked. A man opened it. He must have been about forty years old, with scanty hair combed sideways across his balding scalp. I recognized him because I’d seen him on his balcony many times speaking loudly on his mobile phone.

“Hello,” he said. “May I help you?”

“I’m Farida, your neighbor from the opposite building,” she said. “And I’m here about the birds.”

“Birds?” he said, looking confused.

Farida turned to me with an exhausted expression. “Explain, Mary. Tell him about the crows.”

“Ma’am doesn’t like what you’re feeding the crows,” I said. “She thinks you should not be giving them KFC.”

“KFC? I don’t understand,” he said.

“Don’t deny it!” Farida raised her voice. “This very morning, I saw the birds with my own eyes eating fried chicken and chips from a KFC box on your balcony.”

The man’s eyes narrowed. “Do those birds belong to you?”

“Abdul said crows ought to be treated with respect,” she said. “If you don’t, they’ll punish you.”

“But that’s my problem, isn’t it?” he said.

“It’s not right. It’ll give them indigestion.”

The man sniggered. I took hold of Farida’s arm and said, “Let’s go, Ma’am.”

But she pulled it away and said, “Crows recognize faces.”

“Are those birds your pets?” the man asked. Farida gave him a blank look. “I didn’t think so,” he said. “So I’ll feed them whatever I like.”

“Abdul would’ve complained about you to the Management Company,” she said.

But the man had already begun closing the door. “One more thing,” he said, pausing. “If you don’t like what you see, don’t look.” He slammed the door.

“What cheek,” Farida said, her voice shaking. “He wouldn’t have dared, if Abdul was here.” We turned to go back down the stairs, and when Farida saw Haroon waiting, she became more furious. “Why are you still here? Are you spying on me?” She went down one step and almost fell.

Haroon was quick. He grabbed her arm and held her steady. “Easy, Ma’am.”

She tried to push him. “Stop,” she said. “Abdul wouldn’t have liked you touching me.”

“Let’s go,” I said to Haroon. I lifted Farida’s left arm and put it across my shoulder, and Haroon gripped her elbow. We went down the stairs, taking one step at a time.

Each time Farida wobbled, Haroon said, “Be careful, Ma’am,” and she became angrier. When we reached the ground floor we released her, and Farida steadied herself. She looked like she was about to cry.

“Easy now,” Haroon said.

“Be quiet,” she replied.

“Ma’am hasn’t eaten any breakfast today,” I said. I told him how Mr. Abdul had always eaten an omelet and two parathas for breakfast, and that since he’d died, Ma’am Farida had lost her appetite.

“What nerve you have, gossiping about me, Mary,” she said.

I ignored her and said to Haroon, “Poor Ma’am Farida—she’s all alone, and her daughters are far away.”

“At least she’s got us,” Haroon said, and I agreed with him.

When we finally made it up the stairs to the flat, Farida staggered into the living room and collapsed onto the sofa. Haroon waited by the door.

“Tell him to go,” she said, and waved her arm. Her voice was weak. “I don’t want him here. Abdul said gardeners aren’t allowed inside.”

“Come in, Haroon,” I said. Haroon crossed over into the living room. He walked past Farida, and stood in front of the console where all the family photos were displayed: Mr. Abdul and Farida with their daughters; Mr. Abdul shaking hands with the Education Minister; Mr. Abdul wearing dark glasses and a baseball cap at a university golf tournament. Haroon picked up Mr. Abdul’s portrait.

“No, no, don’t touch,” Farida said. “Just go, please.”

“I knew Mr. Abdul,” Haroon said. “He once found me sleeping under a tree and called me a lazy choora. He also reported me to the Management Committee, and I was demoted.”

“That’s how Mr. Abdul was,” I said. “A real bully.”

Farida looked as if she was trying to say something, but no sound came from her mouth. Haroon looked at the photograph for a few more moments, then put it down. “The past’s the past,” he said. “I’m not the kind of person who holds grudges against the dead.”

“Poor people don’t have the luxury of that,” I said. “Come, Haroon, let’s take Ma’am to her bedroom. She’s very tired and must get some rest.”

“No,” Farida said. “No.” Haroon went to the sofa where Farida was sitting, and bent to help her. She began resisting. “No, no, don’t touch me.”

We lifted her up.

“No,” she said.

“You’re very tired, Ma’am,” I said. She tried to protest, but all she could say was no. Her face was wet. We put her into bed. “Get some rest, Ma’am,” I said.

She moaned softly. “Abdul …”

I closed the door. “Come Haroon, I’ll make us some tea,” I said, and went to the kitchen and put some tea leaves and water on the stove to boil.

When I returned to the living room with a tea tray, Haroon was on the balcony laughing softly. He took some chocolate barfi from the Tupperware in his pocket and crumbled it on the ledge. “A treat for the crows,” he said.

I settled down on the sofa, the way I had seen Farida do a hundred times, and drew her soft shawl over my legs. Haroon sat in Mr. Abdul’s chair and put his feet up on a stool, just the way Mr. Abdul used to.

We sat sipping our tea, and by and by, a crow flew down and began pecking at the barfi.