MISS — minorities in shark science — is kicking ass bringing this science to the underrepresented and opening up the dialogue around why cultural and racial history does count for STEM

Jasmin: I work with communities that haven’t traditionally been heard in conservation, including fishing communities like where my family is from in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. One of my big projects is a local ecological knowledge study that I’m doing with my dad, who is a fisherman in Myrtle Beach. I also run Minorities in Shark Sciences, affectionately called MISS, which was founded in 2020 through a tweet. It was during a time of a lot of unrest and political activation when there was a big upswell of the Black Lives Matter movement. There was a hashtag #BlackinNature going around with people posting pictures of themselves enjoying nature. It was this really beautiful movement on Twitter to say Black people should be able to exist in nature without fearing that we’re going to be harassed, or have the police called on us, or shot.

I came across a picture of one of my future co-founders, Carlee, doing shark research, and I got really excited because I’d never seen anyone that looked like me doing shark research. I felt like I was the only one. I responded to her tweet: You’re a Black girl that studies sharks? I do too! We had our other two co-founders come into the conversation and say: Black girls that study sharks? We’re here! It started out as DMs joking that we should start a club, and it turned into a nonprofit, a whole movement, which four years later now has 500-plus members in 33 different countries. It’s pretty wild that the call was made and the answer was overwhelming.

If you aren’t hearing all voices, you aren’t getting the whole picture, and therefore you can’t actually tackle conservation problems.

We have a vision where seeing a person of color studying the ocean is not weird, where it’s normalized. We preserve biodiversity with sharks, but we also preserve diversity among scientists who study sharks and do conservation because we feel true innovation comes from having people with a diversity of experiences and backgrounds. If you aren’t hearing all voices, you aren’t getting the whole picture, and therefore you can’t actually tackle conservation problems. We’re all about engaging people, whether as scientists working in the field or as community leaders using science as a tool to protect the resources of their community.

We also have an expansive view of what science is—beyond what has traditionally been seen as science. We want people to have the resources, knowledge, and tools that they need to engage in the protection of our oceans because it impacts all of us. We live on a blue planet, and if the ocean ecosystems were to collapse, you’d feel it. Everyone should be part of the conversation, not just a select few powerful people. They shouldn’t be the only ones making the decisions because they don’t have the whole picture.

Jasmin was open with me on my show, and we had a robust discussion around not so much the specifics of her work as a scientists — toothed sharks and hammerheads — but around REPRESENTATION.

No, DEI is not a perjorative. DIVERSITY. EQUITY. INCLUSION.

It’s the affirmation that this is a white settler colonial project, that for centuries was dominated by and overlorded through the White Male.

So, affirmative action is about fighting that bias, bigotry, patriarchy, racism and just plain old Stephen “I am a Jew who is not Jewish” Miller hate, and Donald “Christian Wacko” Trump, both part of the brownshirts of 2025.

In an effort to quantify our successes and learn where we can do better, we were evaluated by Results 1 in 2024. Below are some key highlights!

MISS program participants stated that other programs/organizations do not have the same sense of community as MISS.

When asked to describe MISS in a few words, participants stated the

“MISS is more than an organization. It is a community of caring and supportive people.”

When asked what was gained from participating in MISS programs, participants stated they gained employment and their experience with MISS led to the employment either directly or indirectly and obtained grants, fellowships, or other opportunities to advance their education or career.

+—+

Jasmine had active parents — NAACP, Air Force Mother, and a grandfather who was the first and only gas station owner in Myrtle Beach, Florida.

Here, a question from NYT reporter:

Explain the parallel you draw between the public’s perception of sharks and Black people.

Sharks have a bad reputation. They can’t catch a break in the media. There might be a shark bite and maybe it was a little leopard shark, but what would be shown was a picture of a big, scary great white.

And similarly, in police brutality incidents, when somebody died, what got shown was the most thugged-out picture of this person. Yet people who commit very heinous crimes who are not Black get a graduation photo or something. I started seeing that, Ah, this is the same thing, and maybe we need to use similar approaches to tackling both of these issues.

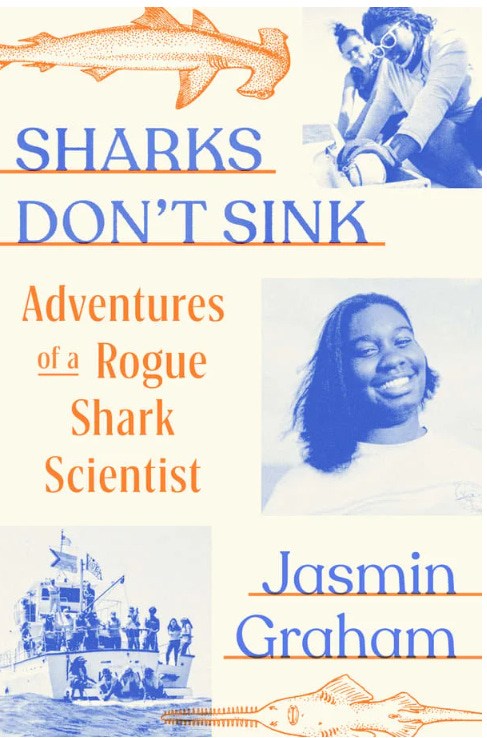

Her memoir is out, at the young age of 30:

The foundation to her science pursuits is indeed rogue in the many times siloed and sacrosanct arena of science.

“Science is supposed to be objective, and people will say to leave the other things about you at the door,” she says. “I don’t agree with that. Our stories, our ancestors, what we care about, our culture—all of those things make us who we are. Science is done by people, and people are biased, so we may as well bring all of our perceptions and realities and experiences into what we’re doing.” If people can do that, she says, it can help change the status quo.

“Do science!” she says. “And if someone tells you that you can’t, don’t listen to them.”

As is true with most memoirs, hers took her to new places, and her own imposter syndrome kicked in — “Who, me, a 20-something young person who has a pretty good life, why would anyone want to read MY story?”

Those are not her words, but her sentiments, and I have seen and heard the very same thing from older adults, in their 70s, who again self-efface their lives. Jasmin’s story, the memoir, is vital for other Black youth, both boys and girls, to get an idea of what success looks like from the STEM world, a la minorities.

“It’s interesting to take a bird’s-eye view of your life and think about the sum of its parts and how they led to this moment,” she explains. “It’s cathartic. It gives everything some purpose or meaning.”

It’s funny that when I dive in Mexico or Belize or the Caribbean, I am the minority, and not just the dive masters and boat tenders are people of color, but so are the scientists. In the USA, Jim Crow 3.0 is hitting us hard. Amazing how that Black President Obama lambasted African Americans for being lazy and disengaged, and now we have full front sadism with Trump and ironically his Jewish General, Stephen Miller.

Jean Guerrero, Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda

DEI: Democratic Demand from the Grassroots,

Here, from the Sarasota magazine:

While Graham has achieved plenty of success in her career already, the road there was marked by potholes and detours. In Sharks Don’t Sink, she writes candidly about her longtime struggles with anxiety and being consistently underestimated because of the color of her skin.

One example: a white teacher who asked, “Are you lost?” on Graham’s first day at her magnet school, implying that because she was Black, she shouldn’t be there. She didn’t meet another Black marine biologist until she was 22 years old, and in graduate school, an older male researcher essentially stole her work without consequence, leading Graham to leave the program. “I wonder if this would be happening to me if I was a white male,” she writes.

+—+

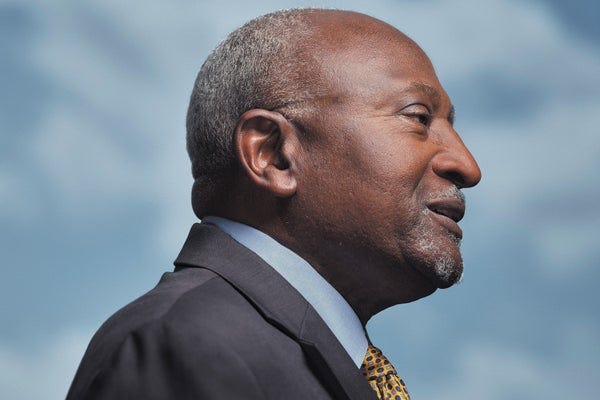

Jasmin riffs with so many topics, that she’s a superstar of sorts, handling Discovery Channel stuff, Bioneers conferences, NYT’s interviews, and even FOX News features. I did bring up another hero of mine: Dr. Robert D. Bullard.

I do what’s called “kickass sociology.” I’ve tried to pattern my work after a kickass Black sociologist: W.E.B. DuBois, who showed how someone can be a teacher, scholar, researcher, author, social critic and activist. He helped to found the NAACP [in 1909]—the oldest and largest civil rights organization in the U.S.—and he did some of the first empirical research in sociology.

Black people face some of the highest cancer and asthma rates in the U.S., statistics that are inarguably linked to the environment in which someone lives, works and plays. But until Robert D. Bullard began collecting data in the 1970s, no one fully understood how a person’s surroundings can affect their health. And no one, not even Bullard, knew how segregated the most polluted places really were.

Bullard was the first scientist to publish systematic research on the links between race and exposure to pollution, which he documented for a 1979 lawsuit. “This is before everyone had [geographic information system] mapping, before iPads, iPhones, laptops, Google,” he says. “This is doing research way back with a hammer and a chisel.”

In 2021 Texas Southern University in Houston established the Robert D. Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice, where Bullard now serves as executive director. He has written 18 books on the topic, and his work helped to launch a movement. Environmental justice—the idea that everyone has the right to a clean and healthy environment, no matter their race or class—has been embraced by advocates around the world and is influencing international climate negotiations. Scientific American asked Bullard about his work and its impact in the U.S. and beyond.

Jasmin Graham, meet Bullard.

Ida-Wenona Hendricks: A Collection of Personal Experiences by Black Women in Marine Science:

Ida-Wenona Hendricks is a Tropical marine biologist, naturalist and budding taxonomist; she shares with us her journey as a Black African female marine biologist. Her unique experiences and the hurdles she has had to overcome in the industry. As a Namibian marine biologist Ida has faced repercussions for questioning neo-colonial practices in her home country. In addition, Ida is helping women of colour to protect their beautiful coils from saltwater in an eco-friendly way.

What is BWEEMS? A Global Community Driving Discovery

Black Women in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Science (BWEEMS) is a global non-profit dedicated to increasing the representation and influence of Black women in STEM. With 600+ members spanning 26 countries, we empower emerging and established scientists through mentorship, professional development, and community-driven opportunities.

Our global community includes:

430+

Marine Scientists

300+

Ecologists

75+

Evolutionists

The Ocean Decade

The United Nations declared 2021–2030 as the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development – a global effort to generate the science we need for the ocean we want. Among the first endorsed Decade Actions was the Empowering Women for the Ocean Decade Programme: a commitment to advancing gender equality in ocean science and ensuring women are at the forefront of science, policy, and governance for our ocean’s future.

At Women in Ocean Science, this mission is at the heart of what we do. We are proud to support this global movement by breaking down barriers to women’s participation and leadership in marine science – from fieldwork and research to policy, communication, and governance. Across all that we do, we bridge SDG 5 and SDG 14, because ocean health and gender equity are inseparable.

The ocean we want must include the women we need.

Get with the program — Trump will die, and Miller, well, he shall go the way of the dodo if women and their allies and armies of antiracists do our WORK.

Listen to our talk before it airs November 5, 2025, on my show: Finding Fringe: Voices from the Edge, even on DEMAND.

On the move — this was FOUR years ago: Jasmin Graham specializes in elasmobranch ecology—the study of sharks, skates, and rays and their evolution. Graham, 26, is a member of Black Women in Ecology Evolution and Marine Science, as well as the American Elasmobranch Society, where she served two years on its Student Committee and interned with prestigious organizations such as the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Fort Johnson Marine Lab, and FWC Division of Marine Fisheries Management.

In January 2020, Graham moved to Sarasota with her four-year-old rescue pup named Iggy to join the team at Mote and become the project coordinator for the Marine Science Laboratory Alliance Center of Excellence (MarSci-LACE) project.