Peter and Karim, in Hong Kong, were open to an interview, on my Labor Day and their Tuesday as their classes are starting at the Chinese University of HK

Here’s Karim’s latest post, the intro:

The most insidious aspect of Western hegemony isn’t its military might or economic stranglehold—it’s the psychological conditioning that makes its victims defend the very system destroying them. Across the globe, millions have been programmed to worship at the altar of Western “civilization,” even as it systematically dismantles their societies, exploits their resources, and condemns their children to servitude.

This conditioning runs so deep that pointing out the West’s crimes triggers defensive reflexes in people who should know better. They’ve been taught to conflate criticism of Western imperialism with hatred of ordinary Western people, when the real target should be the oligarchic structures that exploit everyone—including most Westerners themselves.

You Have Nothing to Say

The facade of Western democracy crumbled under academic scrutiny when Princeton University’s landmark study by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page definitively proved what many had long suspected: America is not a democracy but an oligarchy. Their analysis of 1,779 policy outcomes over two decades revealed that ordinary citizens have virtually zero influence on government policy, while economic elites and organized business groups wield decisive power.

This isn’t a bug in the system—it’s the feature. The oligarchs who control Western governments have spent centuries perfecting methods of control that go far beyond crude authoritarianism. They’ve created a matrix of psychological manipulation that makes people believe they’re free while their every choice is constrained by oligarchic interests.

These same oligarchs who manipulate Western populations extend their control globally through economic domination of other nations’ resources. Jeffrey Sachs, another Ivy League professor and once a darling of the Western economic establishment, experienced his own awakening when he witnessed firsthand how the system crushes any threat to oligarchic resource extraction. His studies on Venezuela expose the deliberate destruction of nations that dare to chart independent courses—particularly when those courses involve nationalizing oil reserves that Western oligarchs had grown accustomed to plundering.

Break Your Psychological Chains to an Evil called “The West”

One of their favorite guests, and mine too: Assal Rad, Peter and Karim examine the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the failure of international institutions to respond effectively. The conversation explores how Israeli propaganda has become increasingly ineffective as images of starvation make their justifications harder to sell, yet Western governments continue providing unwavering support despite shifting public opinion.

Man, oh, man, the Jews of Israel have solid genocidal ground to stand on: Let us put this in a historical perspective: the commemoration of the War to End All Wars acknowledges that 15 million lives were lost in the course of World War I (1914-18).

The loss of life in the Second World War (1939-1945) was on a much larger scale, when compared to World War I: 60 million lives, both military and civilian, were lost during World War II. (Four times those killed during World War I).

The largest WWII casualties were China and the Soviet Union:

- 26 million in the Soviet Union,

- China estimates its losses at approximately 20 million deaths.

Ironically, these two countries (allies of the US during WWII) which lost a large share of their population during WWII are now under the Biden-Harris administration categorized as “enemies of America”, which are threatening the Western World.

Germany and Austria lost approximately 8 million people during WWII, Japan lost more than 2.5 million people. The US and Britain respectively lost more than 400,000 lives.

This carefully researched article by James A. Lucas documents the more than 20 million lives lost resulting from US led wars, military coups and intelligence ops carried out in the wake of WWII, in what is euphemistically called the “post-war era” (1945- ).

The extensive loss of life in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Ukraine and Libya, Palestine is not included in this study.

Nor are the millions of deaths resulting from extreme poverty.

The U.S. Has Killed More Than 20 Million People in 37 “Victim Nations” Since World War II

After the catastrophic attacks of September 11 2001 monumental sorrow and a feeling of desperate and understandable anger began to permeate the American psyche. A few people at that time attempted to promote a balanced perspective by pointing out that the United States had also been responsible for causing those same feelings in people in other nations, but they produced hardly a ripple. Although Americans understand in the abstract the wisdom of people around the world empathizing with the suffering of one another, such a reminder of wrongs committed by our nation got little hearing and was soon overshadowed by an accelerated “war on terrorism.”

But we must continue our efforts to develop understanding and compassion in the world. Hopefully, this article will assist in doing that by addressing the question “How many September 11ths has the United States caused in other nations since WWII?” This theme is developed in this report which contains an estimated numbers of such deaths in 37 nations as well as brief explanations of why the U.S. is considered culpable.

The causes of wars are complex. In some instances nations other than the U.S. may have been responsible for more deaths, but if the involvement of our nation appeared to have been a necessary cause of a war or conflict it was considered responsible for the deaths in it. In other words they probably would not have taken place if the U.S. had not used the heavy hand of its power. The military and economic power of the United States was crucial.

This study reveals that U.S. military forces were directly responsible for about 10 to 15 million deaths during the Korean and Vietnam Wars and the two Iraq Wars. The Korean War also includes Chinese deaths while the Vietnam War also includes fatalities in Cambodia and Laos.

The American public probably is not aware of these numbers and knows even less about the proxy wars for which the United States is also responsible. In the latter wars there were between nine and 14 million deaths in Afghanistan, Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo, East Timor, Guatemala, Indonesia, Pakistan and Sudan.

But the victims are not just from big nations or one part of the world. The remaining deaths were in smaller ones which constitute over half the total number of nations. Virtually all parts of the world have been the target of U.S. intervention.

The overall conclusion reached is that the United States most likely has been responsible since WWII for the deaths of between 20 and 30 million people in wars and conflicts scattered over the world.

To the families and friends of these victims it makes little difference whether the causes were U.S. military action, proxy military forces, the provision of U.S. military supplies or advisors, or other ways, such as economic pressures applied by our nation. They had to make decisions about other things such as finding lost loved ones, whether to become refugees, and how to survive.

And the pain and anger is spread even further. Some authorities estimate that there are as many as 10 wounded for each person who dies in wars. Their visible, continued suffering is a continuing reminder to their fellow countrymen.

It is essential that Americans learn more about this topic so that they can begin to understand the pain that others feel. Someone once observed that the Germans during WWII “chose not to know.” We cannot allow history to say this about our country. The question posed above was “How many September 11ths has the United States caused in other nations since WWII?” The answer is: possibly 10,000. — James A. Lucas

Here, a bio on Karim:

I am interested in how the asymmetrical cultural flow from the West into societies across the world, reinforced by corporate hegemony in a neoliberal global political economy (e.g., dominance in the spheres of social media, the movie industry and fashion), influences the individual psychology of the global population. In particular, the effects of racism/white supremacy, capitalism and colonialism hold my strong attention. My research revolves around questions such as: Why do racism and colorism follow highly similar patterns across the globe; How do (Western) social media platforms perpetuate racial hierarchies in cultures across the globe; What are the psychological ramifications of colonialism; What is the relationship between neoliberal political economies and our understanding of human nature?

Peter? Publications

Social Evolution, Political Psychology, and the Media in Democracy: The Invisible Hand in the U.S. Marketplace of Ideas, Palgrave Macmillan (2019). [Link to sample chapters] [reviews of the book]

“Book Review: Competing Economic Paradigms in China by Steven Mark Cohn,” Journal of Economic Issues (in press). [Link]

“The Merciless Mind in a Dog-Eat-Dog Society: Neoliberalism and the Indifference to Social Inequality,” (with Karim Bettache & C.Y. Chiu) Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34: 217-222 (2020). [Link]

“This Changes Everything? A Possible Future of China-U.S. Relations after Trump,” (with Ana Tomicic) Institute of Chinese Studies Occasional Papers 46: 4-35 (2020). [Link]

“Book Review: A Critical Guide to Intellectual Property by Mat Callahan and Jim Rogers (Eds.),” International Journal of Communication 14: 766–768 (2020). [Link]

“The Road to Psychopathology: Neoliberalism and the Human Mind,” Journal of Social Issues 75(1): 89-112 (2019). [Link]

“Ideology, Values and Foreign Policy.” In Oxford Bibliographies in International Relations. Ed. Patrick James. New York: Oxford University Press (2019). [Link]

“Knowledge in International Relations: One Precursor to Motivated Reasoning among Experts and Non-Experts,” (with Danielle Snider) Journal of Social and Political Psychology 7(1): 2195-3325 (2019). [Link]

“Who is the Neoliberal? Exploring Neoliberal Beliefs across East and West,” (with Karim Bettache and Kristy Chong) Journal of Social Issues 75(1): 20-48 (2019). [Link]

“Book Review: What Is Information? by Peter Janich,” International Journal of Communication 13: 1274-1277 (2019). [Link]

“The Cognitive Structuring of National Identity: Individual Differences in Identifying as American,” (with Shawn Rosenberg) Nations and Nationalism DOI: 10.1111/nana.12416 (2018). [Link]

“Theory, Media, and Democracy for Realists,” Critical Review 30(1-2): 13-35 (2018). [Link]

“The Pull of Humanitarian Interventionism: Examining the Effects of Media Frames and Political Values,” (with Jovan Milojevich) International Journal of Communication 12: 831–855 (2018). [Link]

“The ‘Chicken-and-Egg’ Development of Political Opinions: The Roles of Genes, Social Status, Ideology, and Information,” Politics and the Life Sciences 36(1): 1-13 (2017). [Link]

“A Test of the ‘News Diversity’ Standard: Single Frames, Multiple Frames, and Values Regarding the Ukraine Conflict,” (with Jovan Milojevich) International Journal of Press/Politics 22(1): 3-22 (2017). [Link]

“Anti-Semitism and Opposition to Israeli Government Policies: The Roles of Prejudice and Information,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40(15): 2749-2767 (2017). [Link]

“Review Essay: The Battle Over Human Nature, Coming to a Resolution,” Political Psychology 37(1): 137-143 (2016). [Link]

“Information: Evolution, Psychology, and Politics,” Papers on Social Representations 25(1): 1-40 (2016). [Link]

“The (Intellectual Property Law &) Economics of Innocent Fraud: The IP & Development Debate,”International Review of Intellectual Property & Competition Law 38: 6-30 (2007). [Link]

“The U.S., Impunity Agreements, and the International Criminal Court: Towards the Trial of a Future Henry Kissinger,” Guild Practitioner 62: 193-229 (2005). [Link]

Work in Progress

“When Left is Right and Right is Left: The psychological correlates of political ideology in China” (Under Review). [Link]

“Knowing what the electorate knows: Issue-specific knowledge and candidate choice in the 2020 elections” (Under Review). [Link]

+—+

We didn’t even scratch the surface of Political Economy: Peter Phillips, former director of Project Censored and professor of Political Sociology at Sonoma State University. His new book “Giants: The Global Power Elite” details the 17 transnational investment firms which control over $50 trillion in wealth—and how they are kept in power by their activists, facilitators and protectors.

Ahh, Peter Beattie said things have been messed up for 10,000 years: Think about this evolution of the brain and psyche for two million years, or more, and now what, the Fertile Crescent fucked us up big TIME.

- 2 million years ago: The earliest evidence of a hunter-gatherer culture emerges with the appearance of the genus Homo.

- 1.9 million years ago: The lifestyle became more developed and accelerated with Homo erectus, a species with a larger brain and physique suited for long-distance walking to acquire meat.

- 700,000 to 40,000 years ago: Hunting and gathering was the way of life for later hominins, including Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, who used increasingly sophisticated tools.

- 200,000 years ago to ~12,000 years ago: The hunter-gatherer lifestyle continued through most of the existence of our own species, Homo sapiens. This period ended with the Neolithic Revolution, which led to the development of agriculture.

Locking up the food and fencing in the hunter/ gatherer and nomadic and pastoral lands caused:

- Social stratification

- Specialization and gender roles

- Warfare

While in 1995 there appeared to have been at least a 1,500-year gap between plant and animal domestication, it now seems that both occurred at roughly the same time, with initial management of morphologically wild future plant and animal domesticates reaching back to at least 11,500 cal BP, if not earlier. A focus on the southern Levant as the core area for crop domestication and diffusion has been replaced by a more pluralistic view that sees domestication of various crops and livestock occurring, sometimes multiple times in the same species, across the entire region. Morphological change can no longer be held to be a leading-edge indicator of domestication. Instead, it appears that a long period of increasingly intensive human management preceded the manifestation of archaeologically detectable morphological change in managed crops and livestock. Agriculture in the Near East arose in the context of broad-based systematic human efforts at modifying local environments and biotic communities to encourage plant and animal resources of economic interest. This process took place across the entire Fertile Crescent during a period of dramatic post-Pleistocene climate and environmental change with considerable regional variation in the scope and intensity of these activities as well as in the range of resources being manipulated.

The evolutionary road is littered with failed experiments, however, and Manning suggests that agriculture as we have practiced it runs against both our grain and nature’s. Drawing on the work of anthropologists, biologists, archaeologists, and philosophers, along with his own travels, he argues that not only our ecological ills-overpopulation, erosion, pollution-but our social and emotional malaise are rooted in the devil’s bargain we made in our not-so-distant past. And he offers personal, achievable ways we might re-contour the path we have taken to resurrect what is most sustainable and sustaining in our own nature and the planet’s.

Scroll Down and find the old show above HERE.

+—+

Peter: “The Pull of Humanitarian Interventionism: Examining the Effects of Media Frames and Political Values,” (with Jovan Milojevich) International Journal of Communication 12: 831–855 (2018). [Link]

(Oh, winning those hearts and minds with intervention of the Western Humanitarian (sic) kind!)

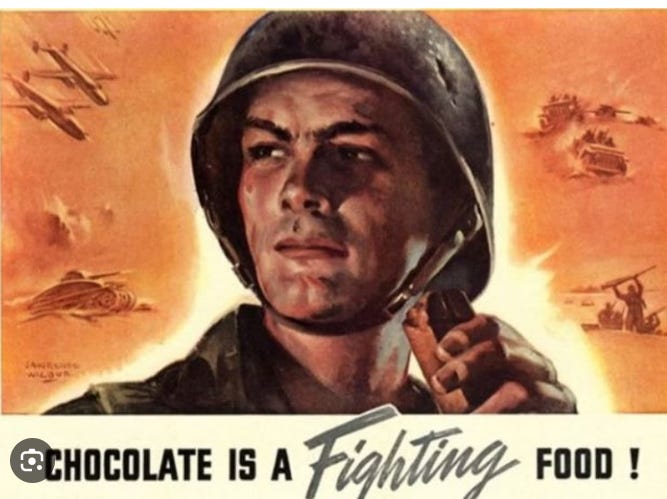

The Candy Man:

Shit:

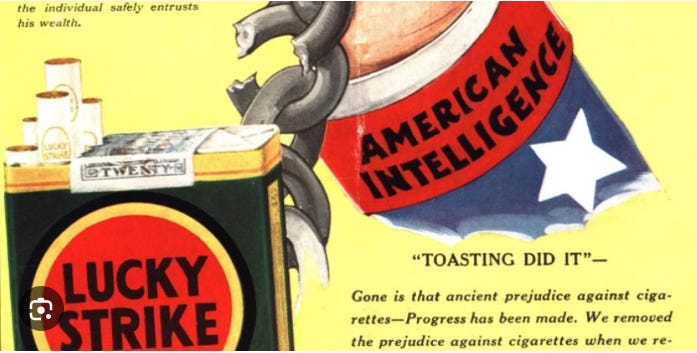

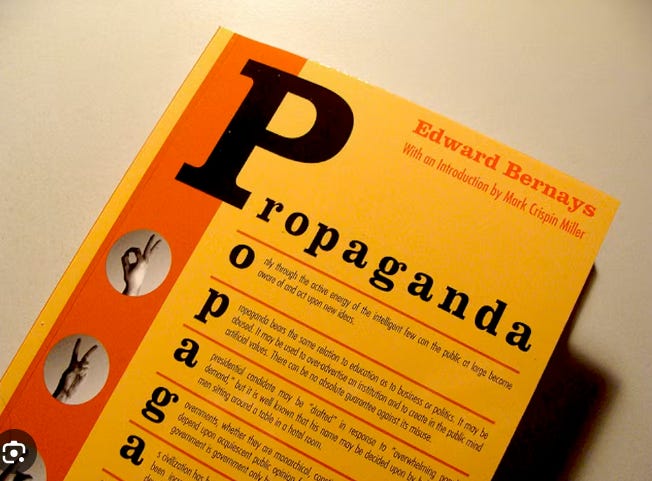

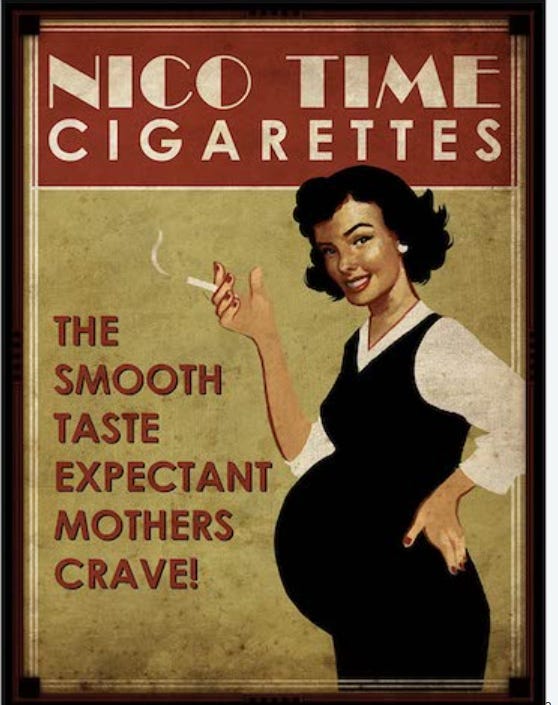

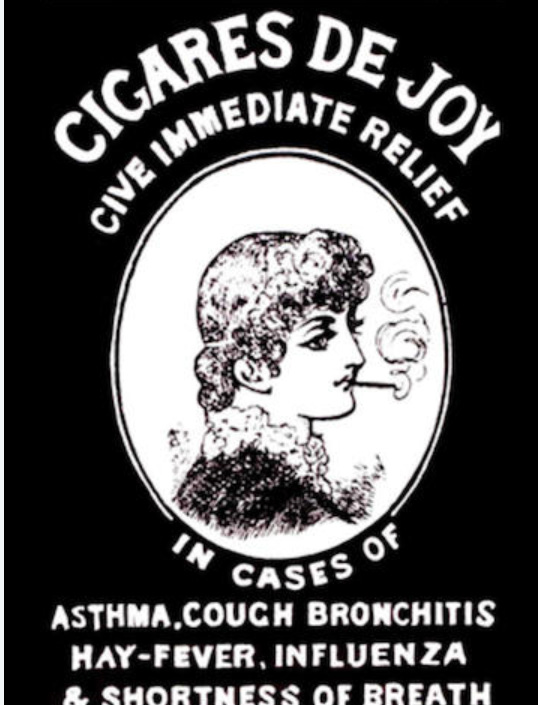

Edward Bernays anyone?

“If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, it is now possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without them knowing it.” — Edward Bernays

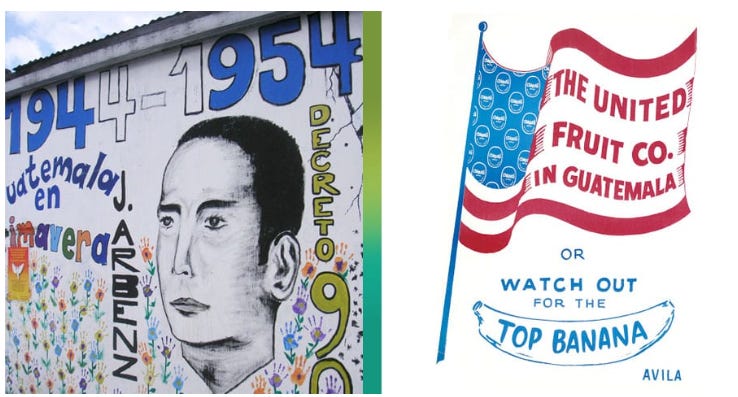

I’m Chiquita Banana and I’ve come to say

I come from little island down Equator way

I sail on big banana boat from Carribee

To see if I can help Good Neighbor policy”The Terry Twins – 1944

We talked about soft (not mashed banana) power:

Edward Bernays’ promotional stunts were only a smokescreen for a not-so-innocent deep-state strategy. With sly public relations tactics, he began to influence American media toward discrediting the new Guatemalan President and ultimately incite action against the duly-elected leader. In 1954, a CIA-backed coup d’état turned the government of Guatemala over to what was ostensibly a leader hand-picked by the U.S. government and indirectly by a U.S. corporation — the United Fruit Company.

Quoting: Peter Beattie

The media create frames to transmit information to the public, and the frames can have varying effects on public opinion depending on how they combine with people’s values and deep-seated cultural narratives. This study examines the effects of media frames and values on people’s choice of resolution of conflict. The results show that neither values nor exposure to frames are associated with outcome. Participants overwhelmingly chose the humanitarian intervention option regardless of frame exposure and even in contrast to their own political values, demonstrating the influence of the mainstream media’s dominant, humanitarian interventionist frame on public opinion.

In early 2013, the Syrian crisis was growing worse by the day, and violence was escalating at a rapid pace. Then–U.S. president Barack Obama was weighing the option of a full-scale military intervention, based on humanitarian grounds, in the troubled state. Islamic State was wreaking havoc throughout the country; however, it was Syrian president Bashar al-Assad who was primarily making the headlines in the United States for alleged atrocities and violations of the Geneva Accords and human rights. The seemingly perpetual beat of war drums in the United States did not take long to sound off, and they grew louder each day President Obama did not declare war on Assad. The media played along, and, generally, so did the political elite. Even former U.S. president Bill Clinton contributed by stating that if Obama chose not to go to war because Congress voted against it, he would risk “looking like a total wuss” (Voorhees, 2013)—a feeble and desperate attempt to demean the president into taking the United States to war. Former secretary of state Hillary Clinton and Senator John McCain, never ones to shy away from a military confrontation (Johnstone, 2015; Landler, 2016), echoed Bill Clinton’s sentiment as they were both displeased with Obama’s foreign policy decision making on Syria (Landler, 2016; Voorhees, 2013). Highly emotive phrases—popular in interventionist frames—such as, “History will judge us,” “We don’t want to be on the wrong side of history,” “We cannot look the other way,” “The world is watching us,” and “What will and “What will the world think,” dominated the headlines and news reports. Then–secretary of state John Kerry touched on almost all of these in his speech at a State Department briefing in August 2013, at a time when President Obama was deliberating possible recourses in response to an alleged chemical attack by Assad’s forces.

Kerry stated,

As previous storms in history have gathered, when unspeakable crimes were within our power to stop them, we have been warned against the temptations of looking the other way. . . . What we choose to do or not do matters in real ways to our own security. Some cite the risk of doing things. But we need to ask, “What is the risk of doing nothing?” . . . So our concern is not just about some far-off land oceans away. That’s not what this is about. Our concern with the cause of the defenseless people of Syria is about choices that will directly affect our role in the world and our interests in the world. It is also profoundly about who we are. We are the United States of America. We are the country that has tried, not always successfully, but always tried to honor a set of universal values around which we have organized our lives and our aspirations. . . . My friends, it matters here if nothing is done. It matters if the world speaks out in condemnation and then nothing happens. History would judge us all extraordinarily harshly if we turned a blind eye to a dictator’s wanton use of weapons of mass destruction.

…

Continued, Beattie:

One of the main cultural themes in the United States is the nationalism theme, with the global responsibility nationalism theme—which emerged after World War II—being the most dominant. As Gamson (1992) articulates, “With the advent of World War II and the cold war, public discourse fully embraced the global responsibility theme” (p. 142), and the American public threw its support behind the United Nations and the idea of collective security. Democrats and Republicans alike “embraced a dominant U.S. role in the creation of political-military alliances, not only in Europe but in other regions as well” (Gamson, 1992, p. 142). The global responsibility theme was the dominant theme during the Cold War and the framing of the U.S. doctrine of containment, and it continues to be the dominant theme today in the framing of the humanitarian interventionist doctrine.

Prior to World War II, the “America first” nationalist theme was the most dominant; however, the global responsibility (then) countertheme was still quite prevalent. When the America first theme was dominant, the kind of isolationism that it supported “was never incompatible with expansionism in what was regarded as U.S. turf” (Gamson, 1992, p. 141); therefore, the global responsibility (at that time) countertheme actually supported the America first theme rather than countering it. The Monroe Doctrine is evidence of this compatibility, because it reinforced American isolationism—by telling European powers to stay out of the Americas—yet supported U.S. expansionism. The global responsibility countertheme was “reflected in the idea of America’s international mission as a light unto nations” (Gamson, 1992, pp. 141–142), with the belief that the “expansion of American influence in the world would bring enlightenment to backward peoples and confer upon them the bounties of Christianity and American political genius” (p. 142). The global responsibility (then) countertheme clearly embodied the notion of American exceptionalism, just as it does today as the dominant nationalism theme. Nevertheless, we would like to make it clear that we are not claiming that deep-seated cultural narratives in the United States are necessarily pro–humanitarian interventionist. What we are claiming, and will substantiate throughout this section, is that the U.S. media and political elites have tapped into a deep-seated cultural narrative to gain support for pro–humanitarian intervention policy options.

Many Americans believe, just as Kerry and other political elites publicly pronounce, that their country does try to honor a set of universal values around which they have organized their lives and aspirations and that these values include the notion that the United States is the leading “defender of democracy and human rights” around the world and that it is “exceptional.” Regardless of whether political elites actually believe this or whether it is simply rhetoric on their part, the mere invocation of this notion to justify war (much of the time conducted illegally—without United Nations or congressional approval) is troubling on its own. For instance, American exceptionalism “originally meant that the U.S. had a God given duty to impose its government and ‘way of life’ on lands not already under its control” (Pestana, 2016, para. 3), and it was, therefore, used to justify American imperialism. In more recent times, however, American exceptionalism has morphed into a more idealistic notion, being viewed as a

belief that the American political system is unique in its form, and that the American people have an exceptional commitment to liberty and democracy. By virtue of this, American exceptionalists assert that America has a providential mission to spread its values around the world. American power is viewed as naturally good, leading to the proliferation of freedom and democracy. (Britton, 2006, p. 128)