Hawaii? A Dwindling Kalaupapa Population Honors 1st Exiles With Tributes And Tears

But first, a movie I viewed just last night. The fucking Dutch, man, the Dutch:

I was watching this fucking movie, The East, and of course, poor poor blond and Aryan Dutch soldiers raping and murdering brown people!

Psychosis of Whiteness: calling them all fucking monkeys, man. It’s in the Dutch DNA!

The Dutch West India Company (WIC) was the largest slave-trading company and established plantations in the Americas. They transported approximately half a million Africans across the Atlantic to colonies like Suriname and the Caribbean islands of Curaçao and St. Eustatius, primarily to work on sugar plantations.

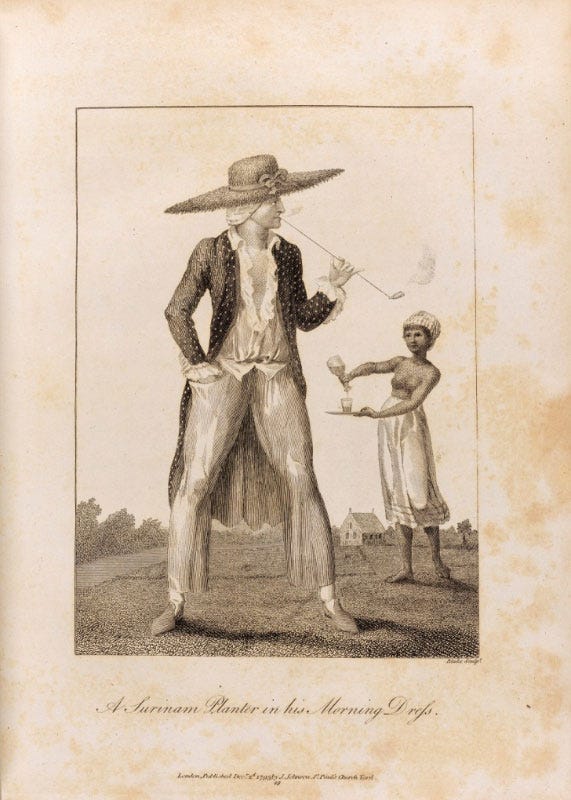

Fucking psychotic cunts: William Blake, A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress.

In the eighteenth century, nearly one-in-ten enslaved people in Suriname had fled their brutal working conditions to establish or join maroon communities, in attempts to live beyond the control of the surrounding slave society. Several maroon leaders, such as Alabi of the Saramaka, rose to prominence and sought independence for their communities by menacing plantation owners and through formal negotiations with colonial authorities.

Shortly after settling in the conquered New World, Spaniards began to use the word cimarrón, of debated etymology, to describe imported European domestic animals that had escaped from control and reverted to natural freedom. For obvious reasons the term was also applied in slave societies to escaped slaves living in freedom outside the world of the masters. It was translated into other masters’ languages as marrons or maroons. That the same word should also be applied by the Caribbean buccaneers to sailors expelled from their community and forced to live the life of nature marooned on some island suggests that freedom was not seen as a bed of roses.

Richard Price, whose Maroon Societies, together with a chapter of Eugene Genovese’s From Rebellion to Revolution provides the most convenient introduction to the subject, is at present the leading authority on marronage in general and on the Suriname maroons (“bush Negroes”), or rather on one of their communities, the Saramakas, to whom he has devoted many years of research. He has already written extensively about them, notably in his path-breaking First Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People, an account of the Saramakas’ establishment and war of independence, based on written records and on their own orally transmitted “strongly linear, causal sense of history,” which is central to their identity and, incidentally, makes them fascinating to historians. Alabi’s World takes the story up after independence, as Saramaka society settled down, and it does so in the form of a “life and times” of one Alabi (1740–1820), who was supreme chief of his people for almost forty years. However, it contains enough introductory matter about the origins of the Suriname maroons to put readers into the picture; for, as the Saramakas say, “If we forget the deeds of our ancestors, how can we hope to avoid being returned to white folks’ slavery?”

The Guardian, in that tradition of quasi-literary movie review — ‘The canonisation of Apocalypse Now has resulted in a cinematic template for the psychological war epic where the battlefields on which indigenous people are brutalised are essentially a backdrop for white soldiers’ internal crisis. Covering the Indonesian war of independence through the viewpoint of the occupier, The East is yet another pale addition to the format, rehashing empty metaphors that are barren of emotional complexity, historical poignancy or visual ingenuity.

The basic history is this: as the second world war draws to an end, the Netherlands sends more troops to Indonesia, hoping to regain their colonial footing as the Japanese occupation of the islands loses steam. Among these fresh-faced recruits is the angelic-looking Johan de Vries (Martijn Lakemeier); unlike the other crass soldiers, De Vries is the “nice guy”, whose goodness manifests in maudlin details like giving biscuits to local kids. His sense of righteousness is driven by guilt; back home, his father is imprisoned as a Nazi collaborator. Still, De Vries will soon be corrupted by an authoritarian superior whose sadism only magnifies the horrors of war.

Ostensibly a critique of imperialism, The East inadvertently commits the same sins as the old empire once did, as Indonesian characters are no more than window dressing. During the bloated running time, indigenous people appear on screen only to be violated and massacred, their screams a mere decorative sound effect. As the film clumsily pairs scenes from De Vries’ life both during and after the war, he is given a degree of multidimensionality that is withheld from the Indonesian characters, who are invariably victims or barbaric aggressors. To travel all the way there only to make a tiresome Heart of Darkness pastiche is a waste.’

[Secretary of State Dean] Rusk affirmed US support for the “elimination of the PKI.” US officials also provided detailed lists of thousands of PKI members for the military and anti-communist civilians, with American officials reportedly checking off who had been killed or arrested.

Amid reports of massacres throughout the country, in late October, Rusk and U.S. national security officials made plans to unconditionally provide weapons and communications equipment to the Indonesian military, while new US aid was organized in December for the civilian anti-communist coalition and the military. By February 1966, Green stated approvingly that “the Communists…have been decimated by wholesale massacre.”

Remember the origins of the Book of Genocide: Jews, man, New Jews of York City.

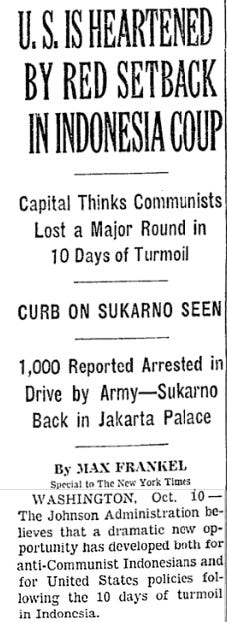

But perhaps the most enthusiastic of all the Times’ writers was Max Frankel, then Washington correspondent, now executive editor. “US Is Heartened by Red Setback in Indonesia Coup,” one Frankel dispatch was tagged (10/11/65). “The Johnson administration believes that a dramatic new opportunity has developed both for anti-Communist Indonesians and for United States policies” in Indonesia, Frankel wrote. “Officials…believe the army will cripple and perhaps destroy the Communists as a significant political force.”

After the scale of the massacre began to be apparent, Frankel was even more enthusiastic. Under the headline “Elated US Officials Looking to New Aid to Jakarta’s Economy” (3/13/66), Frankel reported that

the Johnson administration found it difficult today to hide its delight with the news from Indonesia…. After a long period of patient diplomacy designed to help the army triumph over the Communists, and months of prudent silence…officials were elated to find their expectations being realized.

Frankel went on to describe the leader of the massacre, Gen. Suharto, as “an efficient and effective military commander.”

Evil Jews live a long fucking life: Max Frankel, former New York Times top editor, dies at 94.

He was born in Gera, Germany, on April 3, 1930, according to the Times. His family fled Nazi forces and landed in the United States in 1940.

In a 1999 interview with Diane Rehm, Frankel discussed what it felt like to immigrate from his European home and to find his “tribe” among Jewish people in the States.

“I come here and even in the midst of all this freedom, I’m expected to fight the battle for my tribe,” Frankel told Rehm in 1999. “And when Israel gets in trouble, I’m expected to stand up for them whether they’re right or wrong.”

Max Frankel: The New York Times’ unflinching Jewish journalist

Jews in Paradise: Max Frankel sits front and center when he was the editor-in-chief of the ‘Columbia Daily Spectator,’ in 1952

Fast forward fucking 71 fucking years:

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and USC Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen was disinvited from a book event at 92NY, a cultural center and nonprofit Jewish organization in New York, after he signed an open letter condemning Israel.

“[92NY’s] language was ‘postponement,’ but no reason was given, no other date was offered, and I was never asked,” Nguyen, a professor of English, American studies and ethnicity, and comparative literature, wrote in an Instagram post. “So, in effect, cancellation.”

The event scheduled for October 20 was supposed to feature Nguyen reading from his new memoir, “A Man of Two Faces,” followed by a conversation with Min Jin Lee, the author of “Pachinko.” According to Nguyen’s Instagram post, he and Lee held their event at McNally Jackson Books Seaport instead after receiving news of the postponement five hours before the planned event.

Nguyen signed “An Open Letter on the Situation in Palestine” in the London Review of Books’ blog, which called for an immediate ceasefire and the admission of humanitarian aid into Gaza. It was signed by 750 artists and writers based in the European Union, the United Kingdom and North America.

“Human rights groups have long condemned Israel’s occupation of Palestine and the inhumane treatment of — and system of racial domination over — Palestinians at the hands of the Israeli state,” the letter said. “But we are now witnessing a new and even more drastic emergency. The UN expert Francesca Albanese has warned that Israel’s current actions in Gaza constitute a form of ethnic cleansing.”

In a statement quoted by The New York Times, 92NY said that the attack by Hamas on Israel has “absolutely devastated the community.”

“Given the public comments by the invited author on Israel and this moment, we felt the responsible course of action was to postpone the event while we take some time to determine how best to use our platform and support the entire 92NY community,” the statement read.

Following the event’s cancellation, Nguyen stood by his previous statements.

“I have no regrets about anything I have said or done in regards to Palestine, Israel, or the occupation and war,” Nguyen wrote in an Instagram post the day after the 92NY event was canceled. “I only regret that [event organizer Bernard Schwartz] and other staff at the Y have been so deeply and negatively affected by standing up for art and writers.”

Viet Nguyen: Those identities were always fused or confused. I definitely had the sense that I was American because I grew up completely surrounded by American culture and I absorbed the English language and saw myself very much as someone who belonged here in this country. On the other hand, I was also surrounded by Vietnamese people, had attended all these Vietnamese institutions and rituals and was reminded of the fact that I was Vietnamese by American culture, by things such as America’s movies about the Vietnam War, in which when I was watching them I identified with the American soldiers up until the point they killed Vietnamese people, and I realized I was also the gook in the American imagination, as well.

Steve Paulson: So, movies like Apocalypse Now, Platoon, even the Rambo movies?

Viet Nguyen: Oh, absolutely. I saw all of those and many more. For example, watching Platoon in the movie theaters, I was probably 16 at the time, and going along with the action and everything until this climactic battle where Vietnamese soldiers were being killed, and all of a sudden the audience erupts and cheers. I thought, “Where am I supposed to be in this particular scene? Am I supposed to be cheering the killing or am I supposed to be identifying with the person being killed?”

Steve Paulson: I want to come back to one of those movies, actually, because it figures in a major way in your book. Apocalypse Now. What kind of impact did that have on you, when you first saw it?

Viet Nguyen: I first saw it probably when I was 10 or 11 on the VCR, and it completely traumatized me. I was much too young to watch this movie, did not understand what was going on, but it left a deep imprint on my soul, basically. I still remember it vividly, to this day, particularly for a scene in which the American soldiers massacre a sampan full of innocent civilians. Obviously, this moment for the movie, is meant to signal the descent into darkness for all of these American sailors-

Steve Paulson: This is that scene where they go on a boat and suddenly some of the soldiers go a little crazy and they just start shooting this whole family on the boat.

Viet Nguyen: Right, they kill everybody. Not everyone’s dead. There’s a woman who still survives and the American sailors feel regretful and they want to rescue her but Martin Sheen, the character of Martin Sheen, has this mission to go kill Kurtz. He can’t let anything interrupt his mission, so he executes her. So, it is a turning point in the film, morally, for Americans and for Francis Ford Coppola. I understood that, but that left me so shaken that even 10 years later, in college, as I was recounting the scene to a film class, my voice would shake with rage and anger. This is testimony to the power of the movie and the power of art and the power of storytelling, that I respect that movie very much as being a great work of art. But, it’s also deeply problematic for someone like me, and it gave me the sense that I had to respond in kind, that this novel would be my revenge.

+—+

This one flick, one moment in the fucking racist Colonial timeline of the Psychotic Whites, here we go: The Wind & The Reckoning: A New Feature Length Film Tells the Story of Koʻolau and Piʻilani

For the ʻŌiwi actors, their involvement in the project and helping to tell this particular story amidst a global pandemic was a deeply moving experience.

“As a Hawaiian woman it was a connection to the collective trauma that our people endured. I’m so grateful to be part of this incredibly powerful story. Our story,” Pavao Jones reflected.

“This story is one of the few triumphant stories from the terrible time of leprosy and the overthrow in Hawaiʻi,” said Watson. “Koʻolau and Piʻilani were powerful, strong-willed Hawaiians who rebelled against the intrusive provisional government and prevailed. They refused to bow down to the men that invaded our lands and banished our culture. The first time I read this story I felt very emotional and as I learned more, I felt an immense sense of pride as a Hawaiian.”

SYNOPSIS

1893. The Hawaiian Kingdom has been overthrown by a Western power just as an outbreak of leprosy engulfs the tropical paradise. The new government orders all Native Hawaiians suspected of having the foreign disease banished permanently to a remote colony on the island of Moloka’i that is known as ‘the island of the living grave’. When a local cowboy named Ko’olau and his young son Kalei contract the dreaded disease, they refuse to allow their family to be separated, sparking an armed clash with brutal white island authorities that will make Ko’olau and his wife, Pi’ilani heroes for the ages.

Based on real-life historical events as told through the memoirs of Pi’ilani herself.

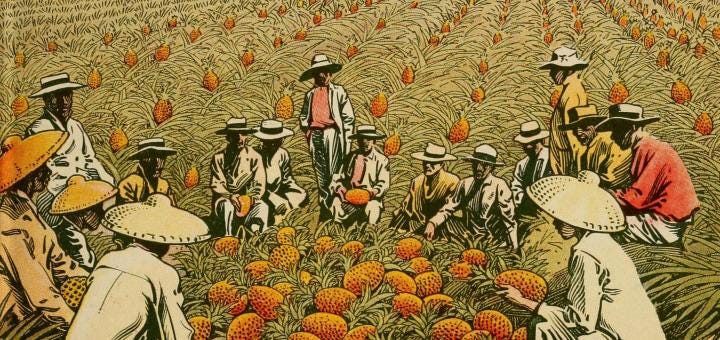

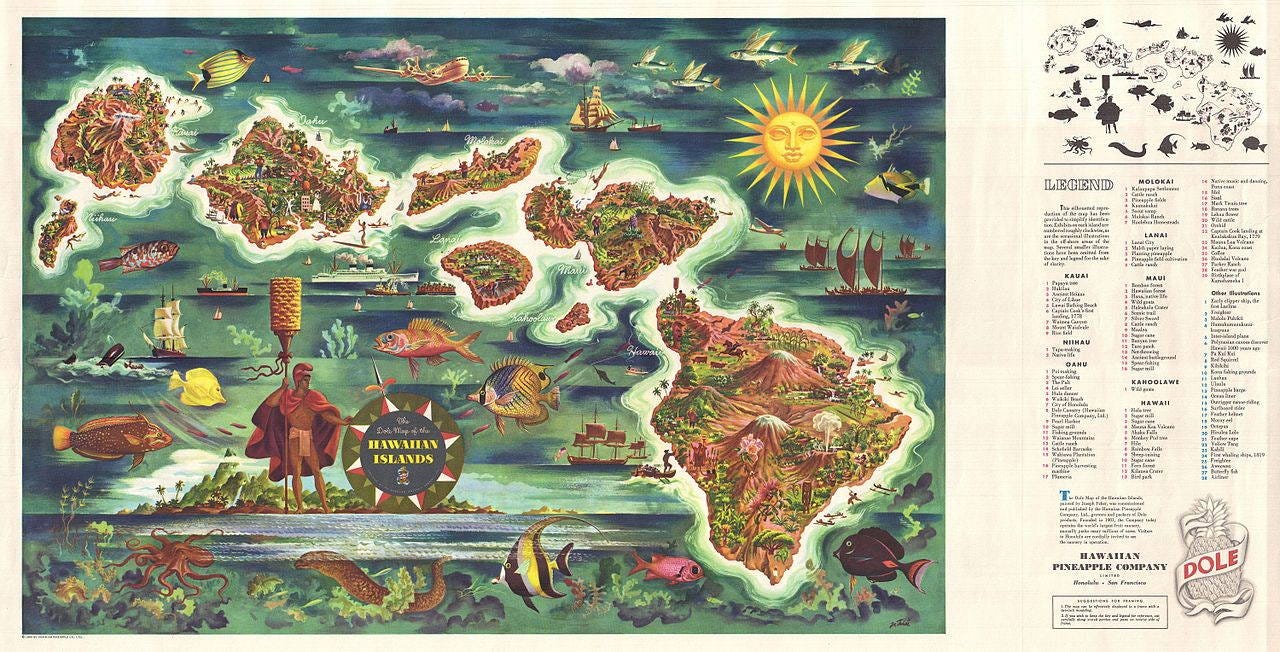

Banana Republic? Pineapples:

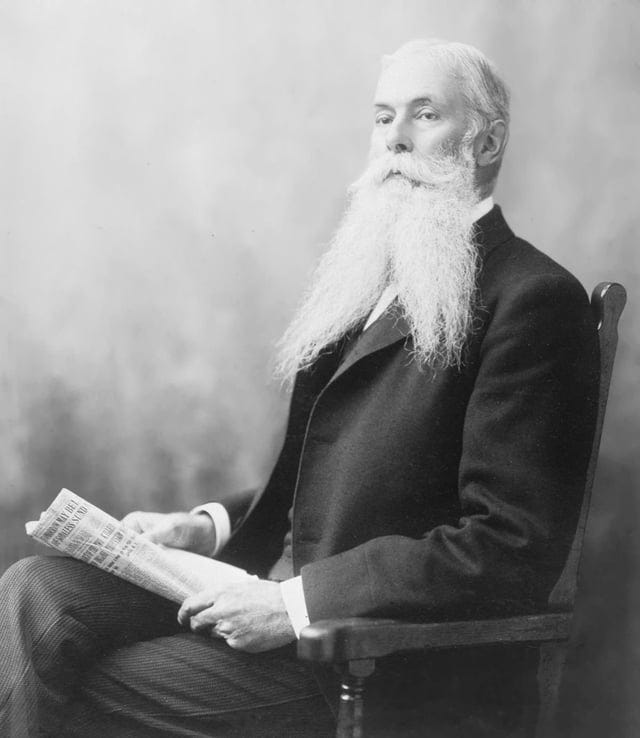

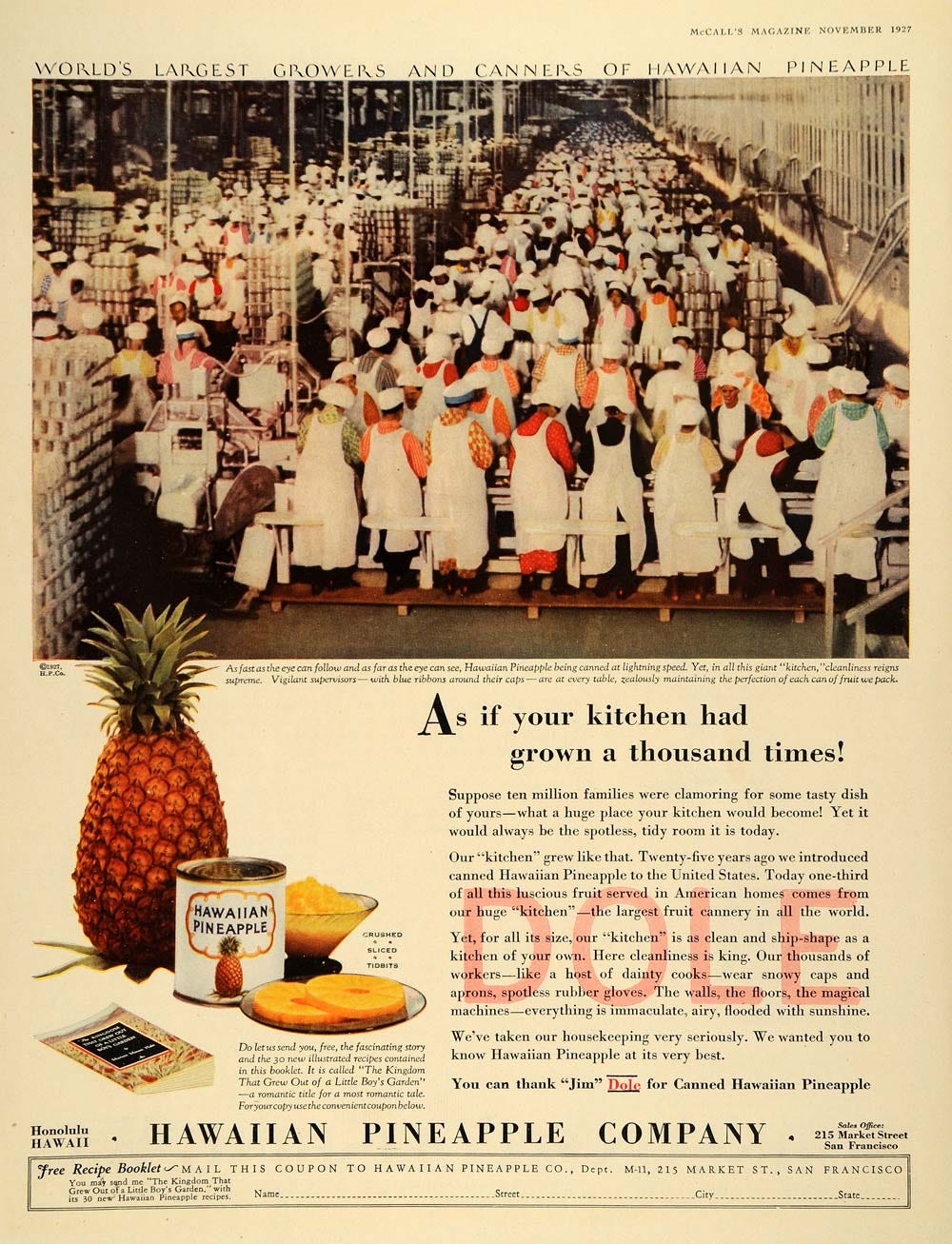

Fucking psychotic whites: Sanford B. Dole, who became the President of the Republic of Hawaii, after a pro-American coup d’état overthrew the Hawaiian monarch. His government secured Hawaii’s annexation by the United States. His cousin founded the pineapple company that would become the Dole Food Company.

Now? Plantation Tourism!!

Despite the economic significance of tourism in Hawaiʻi, the industry has led to environmental destruction and continues to displace Native Hawaiians as they are forced from neighborhoods as real estate prices climb. At statehood, Hawaiians outnumbered tourists two to one; today, tourists outnumber Native Hawaiians thirty to one. Prominent Native Hawaiian activist and nationalist Haunani-Kay Trask staunchly opposes tourism in the islands.

She writes, “On the ancient burial grounds of our ancestors, glass and steel shopping malls with layered parking lots stretch over what were once the most ingeniously irrigated taro lands, lands that fed millions of our people over thousands of years.”

Plantation tourism is the latest iteration of the anguish that has plagued Hawaiian people for over two centuries since the arrival of European explorers in 1778.

In the 1880s, American sugar and pineapple companies grew tremendously on the islands which at the time were subject to the rule of a native monarchy. The businesspeople had a problem with the royalty of the island, and in 1887, people who were affiliated with pineapple and sugar plantations forced Liliuokalani’s brother, who was king at the time, to sign a new constitution. The Bayonet Constitution, which was signed at literal gunpoint, reduced monarchy rule and mandated that only people of certain ethnicities and who were rich enough could vote.

Hawaiian island of Molokai. It was once the site of America’s largest leprosy colony, known as Kalaupapa. About 8,000 people from across the U.S. were quarantined there. For centuries, leprosy was a misunderstood disease. Many believed wrongly that you could catch it from a handshake. Thousands with the disease were taken from their families and exiled to leprosy colonies in the U.S.

And these Cornhusker Klinks and Alligator Alcatraz Trump Innovations come from what?

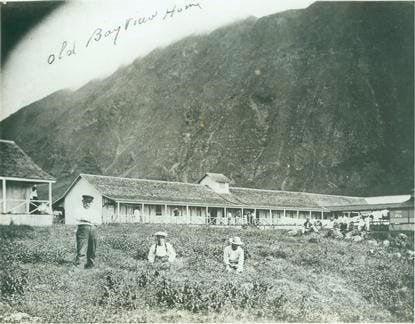

Few places in the world better illustrate the human capacity for endurance or for charity than the remote Kalaupapa Peninsula on the island of Molokai. The area achieved notoriety when the Kingdom of Hawai’i instituted a century-long policy of forced segregation of persons afflicted with Hansen’s disease, more commonly known as leprosy.

This mysterious and dreaded disease reached epidemic proportions in the islands in the late 1800s. At the time, there was no effective treatment and no cure. With new cases threatening to eradicate the native population and no knowledge of what caused the disease, officials became desperate. To government officials, isolation seemed the only answer. In 1865, the Legislative Assembly passed, and King Kamehameha V approved, “An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy”, which set apart land to isolate people believed capable of spreading the disease.

This place was chosen to isolate people with, what was at that time, an incurable illness. The peninsula was remote and fairly inaccessible. To the south, the area was cut off from the rest of Molokai by a sheer pali, or cliff, reaching nearly 2000 feet. The ocean surrounded the rest of the area to the east, north and west. Boat landings were only practical in good weather only. Hawaiians had inhabited this peninsula for over 900 years, so the land could support people. Vegetables such as sweet potatoes, taro, and fruits could be grown in the valleys and on the flatlands. The ocean and tidal pools provided seafood. Fresh water was available from Waikolu and Waihanau valleys.

Once the decision was made, and the law passed, the government proceeded to purchase lands and move the Hawaiian residents to other homes, severing their long connection to the land. The village Kalawao on the isolated Kalaupapa Peninsula thus became the home for thousands of leprosy victims subsequently moved here from throughout the Hawaiian Islands. On January 6, 1866, the first group of nine men and three women were dropped off at the mouth of Waikolu Valley, the closest accessible point to Kalawao on the southeast side of the peninsula. By October of the same year, 101 men and 41 women had been left to die at Kalawao.

Gathered in the corrosive salt air at the Kalaupapa pier, a dozen people listened to a moving Hawaiian language reading of the royal government edict that criminalized Hansen’s disease and outcast those afflicted by it to Hawaii’s leprosy colony.

Former Hansen’s disease patient Meli Watanuki, 88, wiped her eyes with a tissue pulled from the pocket of her puffer vest.

“This is a celebration of our people who are buried here,” she said Friday. “It reminds me of my husband who is buried here, too. I remember all my friends.”

The solemn ceremony marked the anniversary of the arrival of the first dozen patients on Jan. 6, 1866 under a measure to protect the rest of society from a then-little understood and incurable infectious disease.

The event was part of Kalaupapa Month, a designation enacted by former Gov. David Ige last year to honor and remember the thousands of disease-stricken victims who were brutally separated from their families and forced into permanent exile.

Hansen’s disease, commonly referred to as leprosy, is an infectious disease that, if left untreated, can cripple the hands and feet and cause blindness. The disease was long feared to be highly contagious, but it’s now known that it does not spread so easily.

After the discovery of a cure, the Hawaii state government in 1969 lifted the quarantine that for over a century forced roughly 8,000 people to live in isolation at the foot of the world’s tallest sea cliffs. But many former patients chose to remain in Kalaupapa voluntarily as full-time residents.

[Sister Alicia Damien Lau, a Catholic nun who lives in Kalaupapa for the benefit of the last living former Hansen’s disease patients, stands outside the St. Philomena Catholic Church in Kalawao.]

+—+

There is no cure for the living dead:

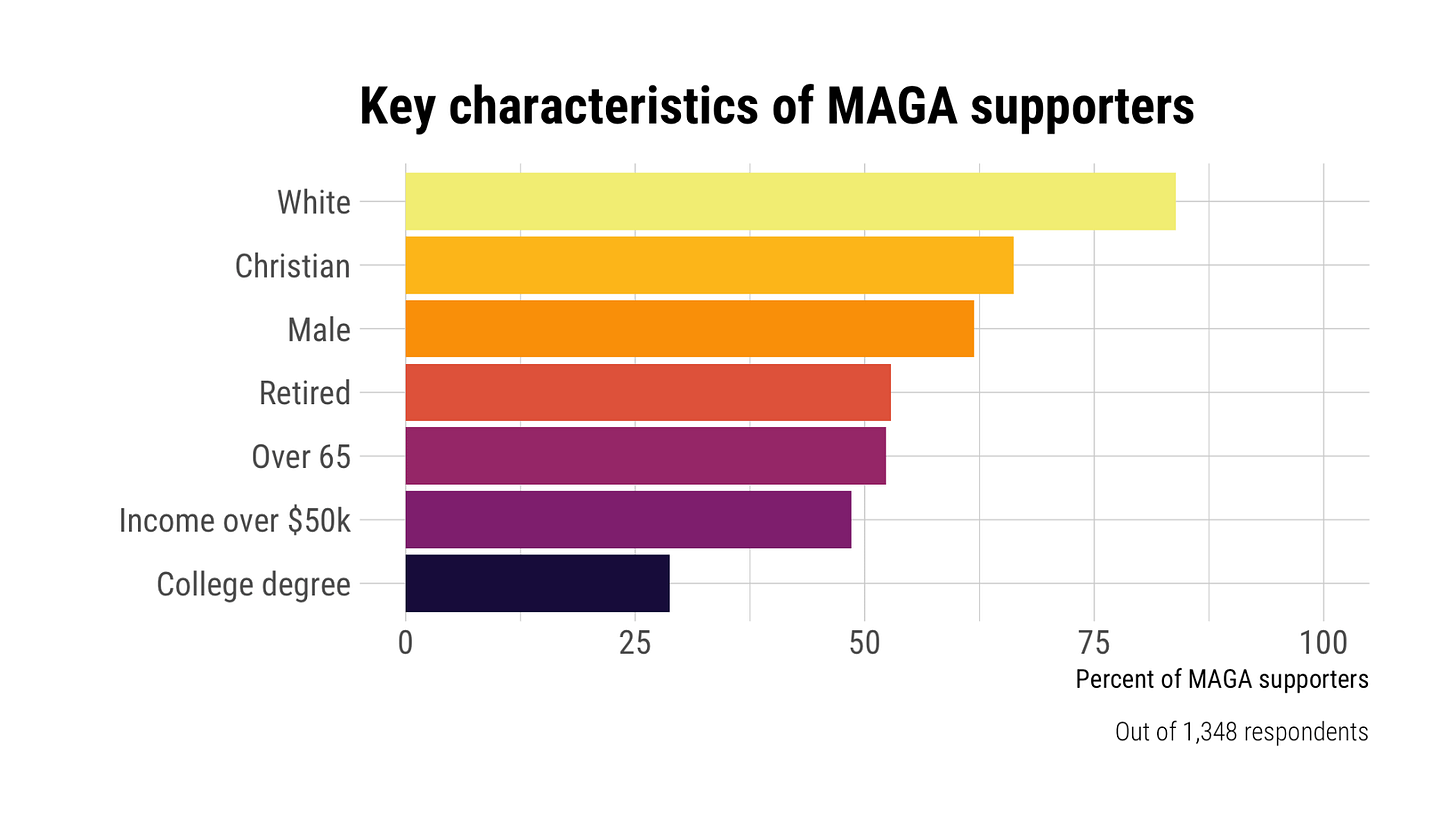

“Tectonic shift in power”: How MAGA pastors boost Trump’s campaign

And, well, the big missing piece below? JEWS. The Rich Cunts of Talmud!