Naming things for humans and earth: Again, a Peace Hike, Jan. 1, in Yachats Oregon, a ceremony for Amanda!

First, some other Native American STUFF:

Redheart Ceremony, Fort Vancouver, Washington (2013):

So, that’s why the little excursion I made with my spouse (ex) to Fort Vancouver yesterday was important. Tied to Nez Perce being incarcerated for doing nothing. Now, 16 straight years, Nez Perce come up from Idaho and have a memorial for that winter in 1877. The little boy that died, he died because of harsh conditions and illegal incarceration. The ceremony yesterday was small, but telling.

City of Vancouver mayor pro tem was there reading a proclamation of peace and admitting the history of that crime; the dignitaries from the National Park, Boy Scouts, military vets, others. Native Americans, sure, some also combat vets — some old fellows with Korea and Viet Nam logos on leather jackets. A couple of WWII logos. Two African Americans dressed up in Yankee garb — Buffalo soldiers. One was 92 years old.

The pomp and circumstance but really Scotty the tribal elder and his mate Uncle (oh, around 95 years old) were there at the head of the circle. Nez Perce flute and song while two eagles and two giant red-tailed hawks screeched above. The riderless horse ceremony with Nez Perce appaloosas and peace pipe ceremony and drumming and the color guard.

Yet, it was the two-year-old boy at the center of the event. A buffalo skin with a pink camping chair, kid-size, and toys and sage bundles. In honor of one child who died near where we were standing over 135 years ago. Emblematic of the entire Indian Removal, India Boarding School, Indian Genocide mess of this country’s grand old flag heritage.

So, I am thinking LaDuke, my years in Navajo and Apache country . . . countless times looking deeper at the history of tribes and great nations here decimated by Spanish, Mexicans, French, British, Canadians, USA.

One of the white guys, with Iraq War — Iraqi Operations Freedom (sic) — logos and patches, he stood out. “I’ll Forgive Jane Fonda when the Jews Forgive Hitler.” You know, this same endless brain-freeze by the dumb and dumb-assed. I’ve dealt with these guys ALL of my life, starting as a military brat, both the Air Force and Army, then as a reporter, teacher, protester. Had it out with some in Guatemala, Honduras and Belize — current or past US military advisers and profiteers and actors in the bloody civil wars.

Members of the Nez Perce Indian Nation will present their traditional memorial ceremony on the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The nearly three-hour ceremony will begin at 10 a.m., Saturday, April 20, across 5th Street from the reconstructed Fort Vancouver.

The ceremony, presented by the Nez Perce Nation, in cooperation with the City of Vancouver, the Fort Vancouver National Trust, and the National Park Service, pays tribute to tribal ideals, honors tribal ancestors and helps to heal old wounds.

During the Nez Perce War of 1877, as the U.S. Army was attempting to remove tribal members from ancestral lands, 33 members of Chief Redheart’s band were captured under the direction of General O.O. Howard. Even though the band neither fought in Indian Wars nor committed any crimes, they were held prisoner at Fort Vancouver through the winter of 1877-78. During the imprisonment an infant member of the band died.

Ceremonial activities begin at 10:00am and include singing, speeches, a Riderless Horse (empty-saddle) ceremony and a traditional passing of the peace pipe. All U.S. military veterans are invited to join the ceremonial circle and be recognized.

+—+

A Blue Flower, Digging Hands & Camas Bulbs for the Good and Hard Times

Paul Haeder, journalist — Spokane 2004/2006

Ancient Earth, Mother Womb

The process of turning up earth and shaking off soil from the roots of a bulb is as old as human time. From Arctic regions to the US Southwest, from the foothills in Bhutan, to the outback in Australia, from the Amazon Basin to the Sahara, wherever humans journeyed and settled, digging into earth for the tuber, bulb, root sustenance of mother earth has always brought with it the ritual of sharing with family and tribal relationships.

For the Nez Perce and other first nations tribes throughout this area (Umatilla, Yakama, Colville, Salish, Kalapuya, Couer d’Alene) their particular digging grounds are sacred places where the camas, an onion-like bulb from the species the Camassia quamash, grows in abundance and is harvested in July and August.

I was lucky enough to have been invited on a quick journey at the beginning of September to traditional camas digging grounds with Grey Owl and his wife Martha Oatman, members of the Nez Perce Tribe. The husband and wife team instructed me on the ethno-botany of such important Nez Perce plants as bear grass, mountain tea (Labrador tea), and dog bane (Indian hemp), but more importantly they shared their tribe’s deep connection to earth skills like camas digging and its eventual cooking and storing, as well as where to find kaus-kaus (qaws-qaws), a gnarly root that has such healing properties as lowering blood pressure and is used as an anti-bacterial/fungal/ bacterial medicine.

The gift that they afforded me which will live in memory was the deep-running narrative history of their people as they floated me back to a time of old ways, in valleys and forest 30 miles northeast from Kamiah, Idaho, following the cut banks of the Lolo Creek.

Troubled Girls Sweat Back to their Centers

Before digging for camas and qaws-qaws, I had to journey back into my own heart by witnessing the modern world bisecting the old. I sped down from Spokane to a spot on the Clearwater River (the Nez Perce call it “little river” and the Columbia “big river”) west of Orofino, Idaho, anxious to meet Grey Owl, who was at a camp with fellow spiritual and Indian skills guide Grey Wolf. The two had finished a day-long series of education and healing workshops at the Clearwater River Company’s tepee rendezvous working with a group of 17- and 18-year-old girls from a youth redirection program called Spring Creek located near Thompson Falls, Montana.

The nine girls had just finished a purification in the sweat lodge, a physically healing and enlightening process most non-Indian folk never will partake in.

“I didn’t know whether I would do a sweat or not when I was hired to work with these girls. It’s a matter of determining on the spot while I’m with them if certain people are going to take it seriously or not,” Grey Owl said. “I don’t hire out my sweat lodge, and it was a matter of gauging whether the group was right for it. These are girls who have gotten into drugs, sex, and boyfriends who have beaten them up … whose parents have money and send them to these programs to fix them. I always say there are never bad kids, just bad parents.”

The girls had just helped build a campfire and were ready to have their cathartic and synergistic moment as Grey Owl led them through the talking circle with an eagle plume that was passed from person to person while each feather-holder reclaimed something about herself. The fire drew us into deep thought, at this place where Lewis and Clark and their band probably learned from the Nez Perce how to dig out 45-foot canoes. Each articulate girl considered the enormity of her wayward ways, her place on earth as woman. They deeply thanked Grey Owl and Grey Wolf for their spiritual guidance, breaking down in tears for the gift of knowing two men who really cared about their futures.

Variations of the mantra, “I am pure, I am strong, I am beautiful, and I am a worthy, free, powerful woman,” ended each girl’s talking round, many of which centered around troubled pasts and new beginnings.

Old Ways Bring in Harvest of Bulbs, Stories, Strength

There are supposedly seven species of camas in this part of Nez Perce country, six of which are poisonous. The very act of going to the fields – a variety of grassy wetlands – when the camas are in bloom in May and June allows the women and girls (it was a woman’s duty in the old days to dig and prepare camas, but not so today) to pull out the bad species, including a white-flowering camas called “the death camas” because it will kill you soon after eating it, Martha said.

The camas that the Nez Perce, Salish and other tribes use has a beautiful blue flower. The camas was once so prolific and abundant that in some places along the Flathead River early white travelers mistook fields of its blue flowers for distant lakes.

*****

“While the digging may have been hard work there was still the cooking to be undertaken before the camas could be used. True, some of the bulbs were eaten fresh as we do green onions, but this accounted for only a small portion of the crop. The bulbs would keep for some time, just as onions do, and there would generally be some to be found in camp in summer. By far, the major portion of the crop was either boiled or roasted,” writes Steven Doyle in his book, Food and Medical Plants of the Colville Area.

*****

For more than 10,000 years the journey to camas fields has fulfilled many tribal nations’ connection to the very earth from whence they sprang. Archaeologists have found camas ovens in what is now Oregon that date back 4,100 years, and other such “scientific research” has revealed evidence indicating that this variety of the lily plant has been part of the diet of the Native Americans in the Willamette Valley for 8,000 years.

Dried or canned camas – which first goes through a process of digging, peeling, cleaning, air-drying, and then roasting in a stone-lined pit and covered with wet bear grass, alder leaves and topped with a less intense driftwood-stoked fire for three days – is in high demand, but few contemporary members of the Nez Perce are willing to go through the physical labor of the camas way.

Only 100 families use the special spot, said Martha. Tse tal pah, Martha’s native name, is the great-great-great granddaughter of Looking Glass, the Nez Perce brave in charge of warriors and who was killed by the US Army at the Battle of Bear Paw (Montana). Martha’s Nez Perce name translates to”leader,” and she was named after the 15-year-old girl who was the only Nez Perce out of all the young and old, male or female, willing to face a hail of Army bullets to retrieve the Nez Perce’s rifles that they voluntarily stacked under the Army’s flag of truce.

“She just kept going back and forth and bringing rifles so the Nez Perce could regroup and hold off the Army. Few escaped that massacre, but Tse tal pah made it to Canada and she had a son who had a son who had a daughter who gave birth to Tuk luk sema – which means ‘seldom hunts’ – and that is my wife’s father, who is a fisherman,” Grey Owl recounted.

Seeking camas is part of a process of fusing with Nez Perce memory and narrative design. But the nitty-gritty of camas harvesting is pretty interesting on its own terms. To get large camas bulbs, the soil has to be worked yearly, benefiting from human agricultural manipulation as the digging clears away weeds, grass and the encroaching smaller bulbs as well as aerates the soil. Grey Owl and Martha this year have dug up 30 gallons of bulbs, camping along the camas field on weekends in what turned out to be a very hot, dry August.

The holes that have been excavated have to be filled back in to heal the earth and to ensure a new season of camas crops.

While camas isn’t supposed to be sold, a small portion of dried or jarred camas can fetch more than $30. Umatilla and Yakima tribal members travel to the very spot I was taken to because of the abundance and size of camas.

We took with us modern-day versions (metal) of the ancient digging tool tuukes – a three-foot, curved spiky fire-hardened wooden tool with a T-shaped antler handle – and canvas bags, as our duty was to sit on earth, upturn 12-inch deep clumps of earth, and break apart with fingers the clods where the camas bulbs – from almond-sized to chicken egg-sized – were nestled.

Signs of digging and filled-in trenches from weeks earlier could be seen, evidence that the “aunties” were doing the hard labor of love that has been passed down generation after generation for thousands of years. While I was there with my hosts, another husband and wife team, who requested their privacy be protected, set up an umbrella and went to unearthing their harvest of camas.

Even though camas harvesting goes back as a traditional, secretive gathering among many families, the tribe does regale in its transformative nature. The annual Weippe Camas Festival (held May 24-25, near Kamiah, Idaho) commemorates the role of camas in Nez Perce culture and the arrival of Lewis and Clark. “The Camas Prairie was named because the plant was so abundant,” said tribal member Gwen Carter, who spent her juvenile years harvesting the camas in a traditional digging area. “I know my grandmother and aunts went digging as children, and I learned from my mother.” Carter, like Martha, Grey Owl and others, wants to keep the root as part of the Nez Perce diet and to preserve the last remaining digging grounds.

The men in Lewis and Clark expedition 200 years ago tasted the sweat fig-like potency of dried ground-up camas; in fact, Lewis recorded extreme stomach cramps running throughout the 28-man company, probably due to raw camas dining. “Camas is a complex carbohydrate that needs special preparing and cooking to be digestible Severe gas and stomach pain can result if not properly prepared,” Grey Owl said chuckling.

*****

Diary – Wednesday, June 11th 1806

“… soon after the seeds are mature the peduncle and foliage of this plant perishes, the ground becomes dry or nearly so and the root encreases (sic) in size and shortly becomes fit for use; this happens about the middle of July when the natives begin to collect it for use which they continue untill (sic) the leaves of the plant attain some size in the spring of the year.” — from Merewether Lewis’s journal

*****

Many like Grey Owl speak of how the traditional camas digging areas enticed the Nez Perce to travel outside their 1863 reservation bounds, largely contributing to the start of the 1877 war with the United States (Chief Joseph became the tribe’s negotiator with Washington DC).

When I asked Martha how long it took the pre-modern generations of aunties to cook the camas, she stated – “from three hours to three days, depending on how close the soldiers were” to the camas grounds. She and her husband hope that a tribal program that reintroduces traditional ways and thinking young folk — Students for Success – will also incorporate camas harvesting into the curriculum so young people can learn the whole process as just one of many important cultural traditions.

Digging brings with it a time for reflection. Deer jump out of shadows. A bull moose lounges near a pound. The sky, pines and cedars morph into one space where brown hawks look for muskrat and camas rat (pocket gophers). And stories are unleashed with each rip of earth, each mixing of sweat with the tiny camas bulbs that are put back into topsoil in order to aid future yields and harvests.

Dig and reflect. Dig and talk. Martha’s humor is wry and active.

I learned that the common Powwow dance, “Duck and Dive,” was born out of the Battle of Big Hole (Montana) when the officers of the cavalry told the soldiers to “aim chest high at Nez Perce warriors.” My short camas digging ritual was peppered with much tribal lore, wisdom, politics, and generations of narrative threading.

Writing about camas could easily take another ten pages just to capture the essence of how spiritual grace and incredible histories are tied to the simple journey to ancient camas fields.

I was also taken to search and dig for the qaws qaws that is in swampy dark forest in amongst ferns. It’s a powerful medicine used in sweats and to heal. I’ve got my own stash now in my basement drying. I’ll be looking for the camas blooms at Turnbull State Park next spring. I’ll search for the white starry blooms of the qaws qaws on my next summer hike in some western Idaho haunt.

To demonstrate the value of a food or medicinal source to a tribe, I was told of how the Kamiah-area qaws qaws root was traded throughout Montana, Wyoming, and even as far as the Dakotas hundreds of years ago, which is how the Nez Perce acquired the best appaloosa horse stock. The Cherokee, Cheyenne, Lakota and other tribes would take a look at the Nez Perce’s big qaws qaws roots and their eyes would pop out of their heads.

Few people today look for qaws qaws or camas because it’s hard work and takes time to clean, dry, and prepare.

Grey Owl beamed when he recalled the previous year’s digging of camas with a six-month pregnant woman and her spouse digging alongside. The pregnant woman’s goal was to dig enough camas to prepare as food for her infant during the upcoming winter.

White Culture’s Attempts at Stripping Away

Once the reservation system was entrenched, tribes faced losing connections to ancient land and long-utilized food and medicinal preparations. Their resilience against the early US government is profound, even ironic. Take Indian fry bread, for instance, which is a feature at fairs, carnivals, and Pig Out in the Parks. It was born out of the vindictive practice of white settlers and their government when they forced tribes to take stale, years’ old almost useless wheat that had to be pounded and ground up. Its only palatable use was for flat, deep-fried bread.

The 1855 Treaty has been broken year after year, and in fact just this summer in Kamiah an elder and his son were arrested after SWAT team intervention for “getting an elk out of season.”

Hiding stores of camas in caves and in pits has saved many a tribe. Lewis and Clark and their men were really bad off when they encountered the Nez Perce nation, who fed them “little river” salmon, gave them potions of qaws qaws and let them taste camas, all of which revitalized them to continue on their journey. Back then, the best young female camas digger could land the best choice of a husband.

The marriage I made during my short tutelage was the reinforcing of my sustainability development and deep ecology philosophy combined with the Nez Perce ethos of “take a little here, leave a lot there.”

“Camas, like the spring salmon runs, is all tied to a circle – a great circle that is a cycle within the culture. Everything is tied together. Please remember that when you write your story,” Grey Owl said with a goodbye hug.

Epilogue

On my way back, I passed the empty tepee camp where just 24 hours earlier those young women had gathered in an attempt at healing their modern ails through the wisdom of the two part Indians. Grey Wolf and Grey Owl. I thought of people in the fields I had just met who were reconnecting to Old Ways separate from the hustle and bustle of their modern lives.

I still have the echoes of those animals nearby where I was digging like an Irishman looking for spuds. And the ghosts of Tse tal pah and Tuk luk sema’s elders are still with me. I’ve tasted the camas, bloodied my fingertips on Nez Perce soil, and sweated dreams of a time that will never be lost, to them or to me, a white man.

Heart of the Monster – Nez Perce Creation Story

It starts with Coyote – it’se ye ye — hearing the other animals of the forest running afraid and speaking of a giant monster. He’s wondering what all the fuss is about as he encounters frightened, trembling animals who say the monster is gobbling up all the forest’s animals. He prepares seven knives made of stone. And then he confronts the huge monster. The monster swallows him up. On the way down, Coyote runs into Rattlesnake who hisses at him. Coyote says, “Yeah, you think you’re scary?” Coyote hits him in the head and that’s how Rattlesnake got its flat head. Then Coyote runs into Beaver on the way down into the monster’s belly. Coyote hits Beaver’s tail, and that’s why today Beaver has a flat tail. Then he meets Bear, and Coyote punches Bear in the face, and that is why today Bear has a flattened face. Coyote then cuts at the Monster with the knives. The first knife breaks, then the second, until he’s got only the seventh one, whereupon he cuts open the Monster. Muskrat tries to escape from the belly, but before he does, Coyote grabs his tail and that’s why today Muskrat has not fur on its tail.

Coyote cuts up the Monster’s heart and flings this piece over the land. Where one piece falls, that’s where the Umatilla tribe spring up. Another piece west, and that’s where the Yakima rise up. All the pieces of the monster get flung far and wide, and that’s where each tribe is born up. All the pieces are gone but there are no Nez Perce people yet. He washes his hands in the river and then sprays the last drops of the Monster’s blood, and that’s where the Nez Perce tribe originates from.

+—+

How Far Do We Go to Save a Species? Salmon Talk!

Robin Waples: University of Washington (NOAA Fisheries, retired)

Topic: On the shoulders of giants: Under-appreciated studies in salmon biology with lasting influence.

In 1675 Isaac Newton wrote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

This idea epitomizes the way that science progresses by incremental steps, punctuated occasionally by major breakthroughs. But often it is the case that neither these ‘giants’ nor their research are well-known or even routinely recognized.

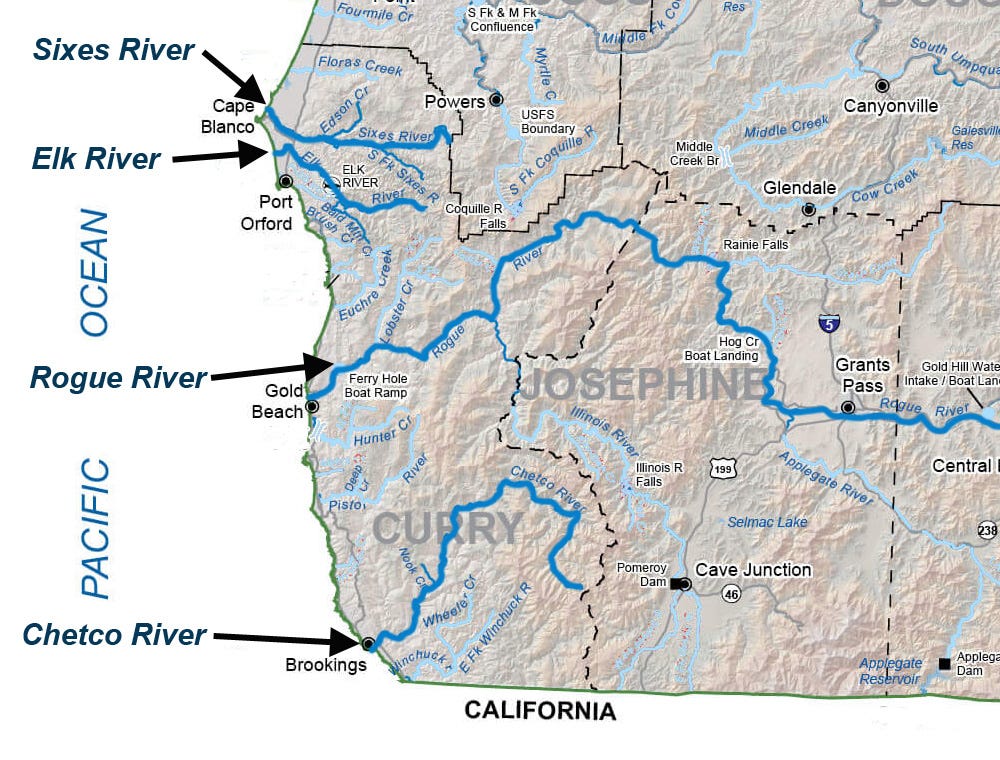

I discuss four such studies conducted in Oregon that have had a profound influence on scientific developments in salmon biology in subsequent decades:

1) a 1960s study of southern Oregon Chinook salmon that was the first documentation of what has come to be known as the Portfolio Effect;

2) a 1970s study of Deschutes River steelhead that was the first attempt to empirically evaluate genetic differences between hatchery and wild fish;

3) a 1980s study of family size variation in Oregon coho salmon that helped pave the way for entirely new lines of research; and

4) a 1980s report on age structure and relative fecundity for Oregon Coast Chinook salmon that provided crucial empirical data to help parameterize models of the rates of genetic drift and loss of genetic variability in Pacific salmon.

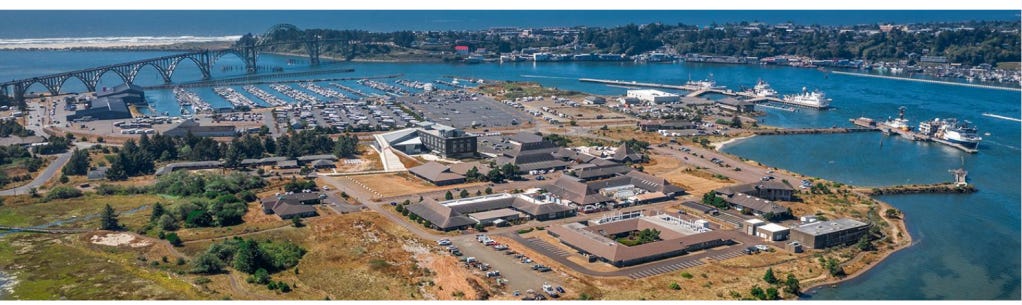

I attended the talk just to be in situ at this Hatfield Marine Sciences Center and see what this 76-year-old fellow had to say = Robert Snowden Waples, Jr., was born 18 January 1947 in Berkeley, California. He attended Palo Alto High School, where he excelled in swimming; he went on to Yale to major in American Studies and to swim, competing with the likes of future Olympians Don Schollander, John Nelson, and Mark Spitz.

He has been at the forefront of wild salmon (and now hatchery salmon) research. He has been cited more than 25,000 times, and he has plethora of articles, and he is credited with helping put ne teeth in the endangered species act for salmon wild species. That is, he and others worked on the varous genetic lines within species so they might get special categorization.

The ESA was set forth to bring a species to a status where it doesn’t need that endangered status. There are more than 50 percent of salmon species listed under the ESA.

The Bristol Bay sockeye salmon fisheries has been and up and down situation. There are 20 to 30 different stocks of Coho salmo, and with sockeye, resilency, representation, and redundancy are key to keeping this ecological area sustainable, Robin states.

While the talk was dry, and there were no photos or videos, graphics from Madison Avenue, he did his talk hoping the audience there was keyed into learning what his top four articles influencing him and the science of salmon research. first article he cited — “Biocomplexity and Fisheries Sustainability” concerning fal lchinook salmon on the Sixes River, OR.

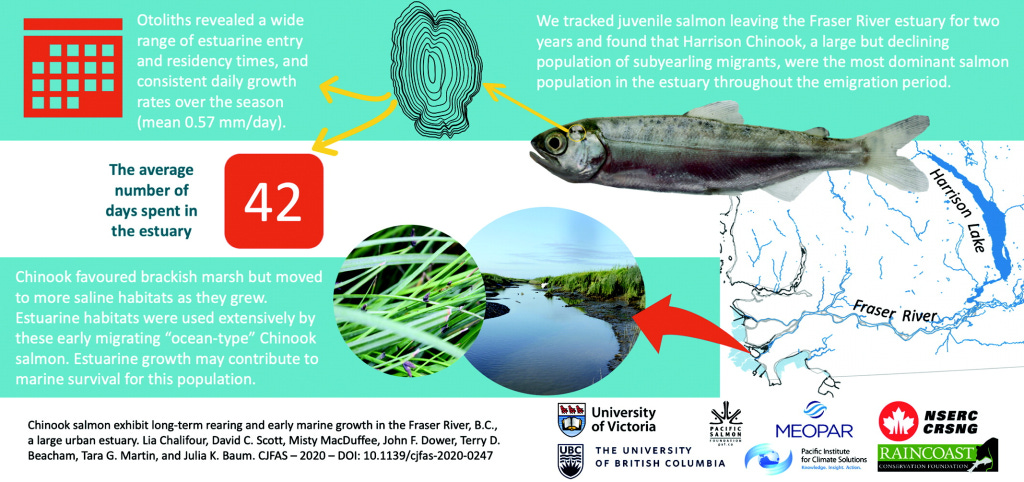

Crazy science, including the slow work looking at adult returns using interesting criteria — fast to the ocean once hatched in home stream; a little time in the estuary after hatching; a lot of time in the estuary; a lot of time in home tributaries; yearlings staying in fresh water for a year.

What helps with survivability. While the 2, 3 , 4 and 5 year returns included mostly those in the third group = a lot of time in the estuary before maturing and heading to sea. This was done in 1965, without Google, the internet and so many other tools.

The next article on Robin’s top four list includes looking atshutes summer steelhead and the genetic differences in growth and survival of Juvenile Hatchery and Wild Steehead Trout, salmo gairdneri.

The question posed in the 1970s research includes: What if there were no hatchery fish? That is, what would that effect be on wild fish? They call that hatchery supplementation since so many wild stocks (more than 50 percet) are endangered, in peril.

The research Robin goes over gets even more deep in terms of genetics and determining the status of coho salmo from WA, OR, and CA. That one was published in 1995.

Lots of work on wild populations and reproductive isolation and life history traied — they can be adapted to local areas.

He cited Valley Creek, near the Sawtooth mountains, where the salmon move from the ocean 900 miles away up to around 6500 feet in elevation.

Of course, the questions from the audience include what about the effects of climate change on salmon community. Robin says there are tons of studies on how salmon sustainability will be changed by warming land and ocean areas. The southern range will have a more difficult time. The northern area will see salmon expansion as the ice receeds and the water gets warmer.

The big questions around what sort of evolutionary changes can help them keep up. These are called evolutionary rescues, but he says warming seas might be too quick for that rescuing to occur.

Reduction in forests and those stream imperilment really affects salmon. Non-point source pollution is huge. More people are changing the land, through urbanization and agriculture. Rainfall and impervious surfaces add pollution loads. Robin states that there is great support for salmon, and most recent polls show 70 to 80 percent people want to work with salmon mitigation and are willing to pay more for salmon and be taxed, as oppopsed to the spotted owl, with only gets 10 percent backing for massive tax increases to save them.

While Robin is not a fan of techno fixes, he is for more streamside tree planting for shading the homes of salmon to lower water temperatures. And making sure water from rainfall gets back into the system clean.

He notes that trout have been put everywhere around the world (trout being a cousin of salmon), and he notes that steelhead and chinook have been put into Patagonia rivers starting a hundred years ago. New Zealand has also introduced Pacific salmon there.

Here’s the talk,

I got to talk with Robin for a few minutes. We talked about his American Studies degree, and how he taught English at the University of Hawaii. And what got him into the sciences. We also mulled over why there is such a disconnect from his and his fellow scientists’ research and the average person including the fisher people who live here in our rural community fishing for rock fish, shrimp, crab, halibut, and other species.

And the issue tied to K12 students NEVER being at these events. And, alas, the problem of higher education pushing MBA programs and programs around coding and software application creation.

I introduced him to some of my work, with David James Duncan, with David Suzuki, and Tim Flannery and dozens of other groups, including Save Our Wild Salmon.

Here, an old one, 2005:

Flat-Earther Bush’s Style for Wild Salmon (Part III of III)

Saving Salmon, Saving Grace — Busting Dams

August 31, 2005

“[T]hese Falls, which have fallen further, which sit dry

and quiet as a graveyard now? These Falls are that place

where ghosts of salmon jump, where ghosts of women mourn

their children who will never find their way back home…”— Sherman Alexie, from “The Place Where Ghosts of Salmon Jump”

One of the greatest contrasts for area residents is how the river Spokane is so powerfully sculpted by nature yet so disembodied from its recent past. The Children of the Sun tribe less than 70 years ago made great snatches of Chinook and Coho near where the Maple Street Bridge funnels SUVs and trucks in an endless stream of belching metal.

Sherman Alexie, best known for Smoke Signals and The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, and a member of the Spokane tribe, does more than lament the loss of the salmon runs. He is confrontational and “in the face” of corporate and political forces that deem salmon as “a fish of diminishing value.”

For Alexie and Spokane tribal elder Pauline Flett, and for groups like Salmon for All and Save Our Wild Salmon, it’s a no-brainer to bring back the clear waters and an abundance of native fish to a river like the Spokane and a river system like the Columbia/Snake.

For some Northwest salmon people, such as Grey Owl, a Southern Cheyenne artist and cultural guide living on the Nez Perce reservation, river and subsequent fish contamination means early, hard deaths.

“Even supposing that we exclude some nefarious government plot to study them,” Grey Owl said, “it is certainly not beyond the realm of possibility that the government was not as careful in the ‘60s about what Hanford released, including radioactive water used to cool the reaction, into the Columbia. Just in our small little Native community here, all salmon people, there is a high incidence of cancers, tumors, and unexplained cysts.”

For salmon and salmon people — including various Inland West and Pacific Coast tribes and non-tribal commercial and recreational fishermen — they recognize three pivotal river systems that incubate and release salmon into the Pacific for the world to enjoy. The Sacramento, Yukon and Columbia/Snake systems are the genetic conveyor belts of wild salmon. For many, these river systems must be unleashed, free of mining and agricultural bleed-offs, and set in riparian and forest cover where clear-cutting is a long-vanished 1900s technology.

More than 45 local, regional and state organizations make up a coalition supporting breaching four dams on the lower Snake River: Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite.

Groups like Friends of the Earth, Trout Unlimited, Northwest Sportfishing Industries Association, American Rivers, NW Energy Coalition, Sierra Club, Earthjustice, Washington Trollers Association make up a cadre of lobbying, informational and advocacy groups poised to support bringing down the four dams.

Save Our Wild Salmon (SOS), as part of the coalition’s main group pushing dam removal, focuses specifically on restoring salmon in the Snake River. Kell McAboy, three years in the trenches as Eastern Washington organizer for SOS in Spokane, has been a vocal public protector of the Snake River and its salmon.

“When thinking about removing the four dams in the lower Snake River, not only is it the best bet for the salmon, it’s the best bet for people. There are more than 200 dams in the Columbia Basin, making it the most constipated watershed on earth.”

The main issues McAboy and others in the coalition see as their stumbling blocks are transportation, farmers and the mythology of having an inland seaport at Lewiston, 900 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean.

“The issue comes down to transportation,” McAboy says. She noted that rail and eighteen-wheeler transportation links can be revitalized in order to move the wheat and other goods the current barges on the dammed Snake provide.

As part of her duties with SOS, McAboy has organized tours of the Snake River, the four dams and free-flowing rivers like the Clearwater and Salmon. Her organization and the coalition at large are connected to a non-profit group, LightHawk, which has planes and pilots at the ready to take people into the air so they might see the environmental impact of dammed rivers from aloft.

“From the air, the people get a unique perspective of how a free-flowing river and the impounded river look like,” McAboy said.

It’s clear when one starts looking at this “to breach or not to breach” debate that there is a definite dichotomy between east and west Washington. Most people for breaching have zip codes set west of the Cascades, while those opposed are from the Inland Northwest.

One strategy Jill Wasberg from SOS in Seattle sees as a way to put flesh and bone on those everyday people who have lost livelihoods and cultural connections because of the death of the natural, large salmon runs, is to foster a sense of story — a narrative lynchpin so the pro-dam breaching stakeholders in this “Save Our Dams” versus “Save Our Salmon” gain voice.

She and others in SOS — with offices in Portland, Seattle, Washington D.C. and Spokane — are interviewing people for a video and publication venture called “The Stories Project.” Wasberg hopes to capture the history, cultural identity and economic value.

Bill Kelley, professor in Eastern Washington University’s Urban and Regional Planning Program, promotes an on-going dialogue “about what constitutes community.” Kelley stresses that a definition of ecology — including river and salmon recovery — should include a “place for humans [and] their needs and desires in balance with ecological capacities.”

“I worry that when our passionate advocacy is too shrill and when our science and comprehensive planning, with all of its complexity, can’t be illustrated in simple and compelling and human terms,” Kelley said, “that we turn off our citizens when we most need to be turning them on.”

As EWU professor, Kelley coordinates undergraduate and graduate students in projects with various communities and constituencies to help them decide how their rural and undeveloped land and their urban space can give them a sense of stewardship and self-determination.

More than 85 rapids and falls will reappear on the Snake River if the dams are removed, McAboy notes. This will result in thrusting volumes of water and no more fattened impounded pools where salmon face nigh nitrogen loads, bacteria and viruses, longer journeys back to the Pacific estuaries, and unnaturally warm waters. Cold, fast-flowing water will push salmon smolt out to sea as nature designed.

Many biologists see breaching and habitat recovery as the only credible salvation to regenerating wild salmon stocks to numbers where sustainability occurs. If breaching is finally approved as the best, most prudent and eventually the most economically sane solution, the four main barriers will be gone, allowing 140 miles of the main stem of the Snake to open up.

This in turn will free hundreds of miles of tributaries in Eastern Washington, Idaho, Oregon and Wyoming for salmon to return full of sperm and roe to breed hundreds of millions of fry that will live and die, leaving millions to transmogrify into river-loving fry and estuary-seeking smolt. Most salmon return to and live in oceans, either close to shore or thousands of miles out to sea, for two to seven years before the evolutionary switch clicks on to return to their gravel beds.

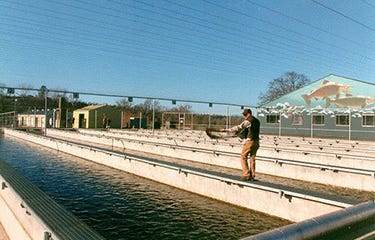

Dave Johnson is a passionate fisheries scientist with the Nez Perce tribe who works to refine and harmonize a dozen tribal hatcheries as a way of supplementing the wild salmon that have been cut off since the Snake River dams came on line in the 1960s and ‘70s. For Johnson, his tribe and others have “a right to fish in all those streams.”

There seems to be a card up the sleeve of various Northwest tribes, including the Nez Perce.

“The Nez Perce are not just some historical artifact,” said David Cummings, Nez Perce legal counsel. Cummings notes that the courts system is just one of several tools; yet treaties signed 1855 and 1856 with tribes of the Washington Coast, Puget Sound and Columbia River stated that while tribes ceded most of their land (1.34 million acres compared to the current 750,000 for just the Nez Perce tribe, as an example), those treaties gave exclusive rights to fish within their reservations and rights to fish at “all usual and accustomed places . . . in common with citizens.”

For Cummings, the 1974 “Boldt Decision” reaffirming tribal rights to 50 percent of the harvestable fish “destined for tribal usual and accustomed fishing grounds” is sort of a cultural and environmental ace in the hole.

Cummings notes that the treaty carries with it a right to restoration of wildlife, including the riverine ecosystem and water quality.

There is a genetic, dietary, and cultural connection to salmon and sustainable harvests. Johnson is one of more than 200 scientists who advocate breaching the four lower Snake dams.

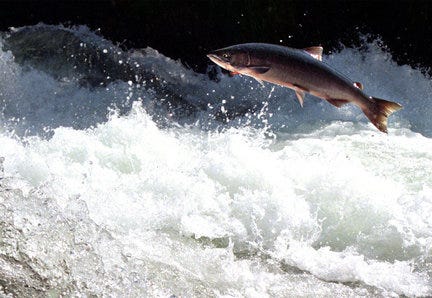

Pacific Northwest salmon for a million years have struggled to recreate their genes by leaving salt water to go upstream. By the millions, wild Coho, Chinook, sockeye, pink, chum, King and others had returned in their respective fall, summer and spring runs. The wild salmon of the Columbia drove their fasting bodies through scablands, falls, and heat to return to their birthing riffles more than 900 miles inland from the Pacific to Eastern Washington and Oregon and deep into Idaho and Wyoming.

That was before the eight federal dams that are the gauntlet stopping the Inland West’s salmon from spawning.

The parallel struggle of overcoming obstacles — now dams — that anadromous fish and the tribes of the Northwest share is telling.

For 10,000 years, Indian tribes rendezvoused at the lower Columbia River’s Celilo Falls. Traders from as far away as Central America gathered with thousands of others from dozens of tribes.

Fast-forward a few thousand years to the Lewis and Clark Expedition as Clark comments on the hundreds of thousands of salmon they came across: “The multitude of this fish. The water is so clear that they can readily be seen at a depth of 115 or 120 feet. But at this season they float in such quantities down the stream the Indians have only to collect, split and dry them on the scaffolds.”

The Dalles dam in 1956 impounded the river, mucked up the cascades and free-flowing nature of things, and inundated the sacred Celilo Falls.

The four lower Columbia dams have been technologically manipulated to allow for safer passage of salmon running to the spawning beds and to allow the smolts to be flushed more safely to sea. The process for the lower Snake River dams, however, is more daunting and less technologically successful.

Most of this country’s 75,000 dams were pounded, cemented and erected into the paths of ancient free-flowing rivers before humans, especially at the political level, saw the big picture of negative biological, cultural and economic impacts of this river-jamming technology, notes Lizzie Grossman, author of the book, Watershed: The Undamming of America.

Grossman read from her just published book at Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane on July 29, emphasizing how “in the past ten years people all over the country have been looking at waterways — how their local creek or river was ignored and abused.” There is a strong sense of wanting the rivers back, including breaching dams.

“America has spent most of its first two centuries turning its rivers into highways, ditches and power plants,” Grossman states. “Now, slowly, we are relearning what a river is and how to live with one. . . . Reconsidering the use of our rivers means examining our priorities as a nation. It forces us to rethink our patterns of consumption and growth and may well be the key to reclaiming a vital part of America’s future.”

“A dam can disrupt a river’s entire ecosystem, affecting everything from headwaters to delta,” Grossman puts into her book’s Forward. “So removing a dam, large or small, is not an easy process. . . . Dam removal alters the visual contours of a community. It is a very public enterprise and is almost always controversial, involving political decisions and civic debate.”

A hodgepodge of liberal environmental and politically conservative groups is pushing to gain political support for the Salmon Planning Act, which states that dam breaching is an option if all other routes to wild salmon species and habitat recovery fail to generate sustainable, healthy levels.

The executive director of Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association, Liz Hamilton, sees dam breaching from a died-in-the-wool capitalist point of view. Her own Republican Party roots and her membership’s conservative bent belie a dynamic most people do not associate with endangered species causes.

“Our industry lost 10,000 jobs in the northwest,” she noted as a consequence of the construction of the eight dams. “Fear mongers have led this issue: ‘If we don’t breach, every single salmon will die.’ On the other side, we’ve heard, ‘If we do breach, we will lose our jobs and way of life.’”

Hamilton sees her group and the coalition’s biggest challenge to convince people of the economic and cultural benefits of breaching dams as psychological. “People fear change. People have to see a future. If they don’t see themselves in it, your average citizen will not respond.”

Hamilton knows salmon restoration is costly. But she sees the Snake River system as a thousand miles of nearly pristine spawning habitat. Hamilton and her coalition lobby people to see a future many resist: removal of the four Snake River dams. “Without the dams we can still transport wheat. We can still generate electricity. We can still irrigate crops. The pressures that people put on the land will still be there when the dams are removed. . . . The cheapest thing to do is unblock a blocked culvert.”

The General Accounting Office reported that more than $3.3 billion in taxpayers’ money was spent by more than a dozen agencies the past 20 years to try and mitigate declines in Columbia River basin salmon runs. On top of that, tens-of-millions have also been spent by state and local governments.

This waste of money has paid for ill-conceived measures and technologies to try and help the fish survive the dams — 34 years of barging fish around dams. Snake River sockeye, Chinook salmon and steelhead were granted “protection” in 1991, ’92, and ’97 respectively through the Endangered Species Act.

Hatcheries have produced more than 90 percent of 2001 salmon and steelhead. Hatchery salmon are not the goal for the diverse environmental and scientific communities because of various issues, including disease, weak genetic lines, and stifling of biodiversity in its natural state. If wild salmon are not rejuvenated, many predict that by 2017 several indigenous populations will become extinct.

Additionally, RAND, a conservative “think tank,” completed a report in September 2002 that posits dam removal on the lower Snake will not bring with it economic turmoil. In fact, the RAND report shows how 10,000 long-term jobs might very well be created and centered right in the economically hard-hit communities that make up the Inland Empire.

Remove dams and help create livable wage jobs and revive a weak Inland Empire economy while preserving sustainable and abundant salmon? The answer seems obvious to most, but for those who resist, there is the 1855 treaty and Boldt decision which cost U.S. taxpayers upwards of $10 to $60 billion paid to the tribes for destroying their salmon and habitat.

“The salmon are our relatives,” Grey Owl said. “The salmon are of this land just as we are. We both share a connection to this land that is hardwired into our DNA. They teach us many spiritual lessons such as the circle of life, giving of yourself to help others, and that our life’s purpose should be to help someone else live.”

Note: Paul K. Haeder teaches college at Spokane Falls Community College and other places. He is a former daily newspaper journalist in Arizona and Texas, whose independent work has appeared in many publications. As a book reviewer for the El Paso Times, many of his reviews appeared in other Gannett newspapers.

+–+

Finally:

A Tribe Once Called “Power from the Brain”

How’d you end up in the Inbred Northwest. . . What act of fate dragged your Texas butt up here. . . You exchanged West Texas, Cormac McCarthy, real Tex-Mex food and sun for this? Or some variation on that theme greeted me when I first bivouacked in Spokane after heading to El Norte from “I fought the law but the law won” Bobby Fuller El Paso, Texas.

It was a hell of a Salmonidae journey, hitching my adult body and soul to the Pacific Northwest in the form of the Inland Empire, Spokane — “largest city between Seattle and Minneapolis,” they kept telling me. My olfactory memory burst with narrative skills by traveling the region as reporter, educator and environmental activist. Man, the work I did on writing about removing those four lower Snake River dams. Pieces on sustainable agriculture in Washington. Stories on the power of storytelling in this region of Earth.

This place is full of river-teeth; the place of Ice Age Floods’ erratic boulders dropped 12,000 years ago from ice rafts in the middle of the Willamette Valley; the ramming tectonics and ring of fire. Luckily for me, writers like Rick Bass, Lizzie Grossman, David James Duncan and so many others kept me busy as a desert salmon looking for some home stream back to the Pacific.

I left Sonora and then Chihuahua for Inland Salish land, where 24 distinct languages once ruled.

NpoqÃniscn, or Spokane. For thousands of years the Inland Salish people here built permanent villages along these powerful rivers in order to connect to their lifeblood and make benedictions to brother-sister salmon. Over three million acres made up their distinct territory, and later other Indians introduced them to horses and plank houses.

It’s a place that encompasses a kind of hope trapped in the way the sun hits water through a stand of cedars and towering Douglas firs. “Sun People” Spokane is translated as, though I’ve talked to a few Spokane scholars who say it’s more closely, “the color of the sun reflecting through the water on a salmon’s back.”

That story dredging is what makes a place, place. The legend about my new home is even more poetic: “There was once a hollow tree. When an Indian beat upon it, a serpent living inside made a noise which sounded like spukcane, a phonetic sound without meaning in the tribe’s language. So, one day, as the tribe’s chief thought about those sounds, these vibrations reverberated from his head. Spukcane then blossomed to mean, ‘Power from the brain.’”

Even a thousand years ago marketing rued the day — Spukanee is what they ended up calling themselves. Children of the Sun.

One of my trips deeper into the spiritual and intellectual fabric of this place (new to me starting May, 2001) was with a contemporary Caucasian writer — David James Duncan. We were talking about dam breeching, slack water rivers, President Bush, war, salmon recovery, and writing. That was April 2008:

I’ve been surprised from time to time by the American people’s eagerness to vote for ways to increase their own suffering and their children’s destitution and Mother Earth’s degradation. But I refuse to despair. Salmon are my totem creature and salmon don’t despair. They keep trying to return home to their mountain birth houses and create a beautiful new generation no matter what kind of hellhole industrial man has made of their rivers. Mother Teresa spoke with the heart of a wild salmon when she said, ‘God doesn’t ask us to win. He only asks us to try.’ I’m in the business of trying. I leave the scorecard to the Scorekeeper.

That journey for me, those tallies by the proverbial Scorekeeper as Duncan frames it, is tied to salmon, as the corpuscles of that species have been in my bloodline for centuries. The blood of Celts and of Scots. Why not? The word “salmon” is from Old French: salmonem, salmo, maybe even from salire.

Salire — to leap.

My mother was born and raised in British Columbia, Powell River. The stench of the largest pulp mill in the world at that time was rotting the alveoli of her lungs and hundreds of others’ respiratory tracks, eventually resulting in emphysema, or what is referred to as COPD.

I remember from one stay there how I noticed a line of cars at the town’s free car washes when the day shift switched to night shift. Acid releases, ash snows, rotten egg winds, and automobile paint flaking.

Both her parents were from Ireland and Scotland ending up on the Sunshine Coast. Some call it Sechelt (shishalh) First Nation land, again, Salish (coastal).

I remember pulling in Coho and King salmon, huge ones in the 1960s. In fact, one that I hooked was close to my eight-year-old’s size, at seventy-five pounds. My Uncle Ted (not by blood, but my grandparents’ friend and boarder) had to take over for me, pulling on the rod with his tobacco-stained hands. His own tired lungs wheezed and rattled while he wrestled the magnificent muscular Chinook close to the gunnels while directing me to gaff it.

Here I was, on this boat along this dark-dark forested coast, with Uncle Ted, friend of my Irish-Scottish grandparents. Son of a chief, from the Sliammon Reserve, 20 miles north of Powell River.

That deep red heart and liver were still connected after Ted gutted it quickly — after some word in his native language he exhorted while proceeding to smash the salmon’s head. He put the heart and liver into an old bucket, the one we used to piss in. As I watched the rhythm of that seven-year-old fish’s power train still pulsating with life in salt water, after being eviscerated, dog fish sharks surfaced near us and gulls dive-bombed our foredeck. Just along the beach a mother and her two cubs paraded around that brown bear way, scenting our kill.

That was almost six decades ago.

Strawberries, spuds and these Douglas firs that stayed with me as shapes long after any J. R.R. Tolkien dreams.

Olfactory memory. I recall those smells on a dive boat off Honduras. I remember the taste of Sockeye blood when I was snorkeling off the Baja peninsula into the thrashing sailfish that was in the grips of a 12-foot hammerhead’s jaw.

Once in Vietnam, along the Laos border, in a bat cave with British and Vietnamese scientists, I tasted that Sechelt cedar fire when Uncle Ted took me and my sister to the “reservation” for a potlatch. Dried smoked salmon was on my deja vu mind in 2006 when I was with Nez Perce friends digging camas in a field near Lolo Pass, Idaho.

It’s cliche but apropos to think some of us are shaped by anadromous destinies, like the salmon, biologically programmed millions of years ago by small but mostly large geologic transformations, and the ice barriers, leaking rivers and creeks caused by melting ice. What got salmon going was the changing nature of the oceans cooling some 30 million years ago.

Theories abound, but the prevailing science says they started out as freshwater fish. Moved to the cold Pacific where nutrient rich waters attracted their ancestors.

That destiny to move, to follow some ancient walkabout song or subsonic calling, it’s been an arousing part of my life. I was born on the ocean — San Pedro, California — and then moved as an infant to the Sunshine Coast in British Columbia.

We moved like migrating salmon, hitching our lives to the tether of my old man’s military profession. I ended up teething on the island of Terceira, part of the Azores, Portugal, about 1,600 km west from Lisbon and 3,680 km east from New York City.

Fish, bread, saints and milagros. Miracles. And stories of fishermen hitting the open waters with poveiro boats launched from the Port of Póvoa de Varzim. Thirty oarsmen making it all the way to Newfoundland. Cod, sardine, ray, mackerel, whiskered sole, snook, whiting, alfonsino and salmon.

Also, tuna, migratory and strong. They’ve been recorded by modern biology traveling some 5,000 miles in 50 days. Albacora these fishermen call them.

Piano wires, hooks and barracuda brought up from the depths. I ate their flesh around beach fires, using colorful upturned boats as barriers from the whipping winds. These fishers talked of sperm whale hunts and monsters from the depths west in the Puerto Rico trench.

A uma profundidade de cinco milha, oito quilometros. More than 26,400 feet down.

Later in college, while working as a dive master in the Sea of Cortez, I was boning up for the History of Hispania course I was taking at the University of Arizona. I read about a 1755 earthquake in an undersea “fracture zone-subduction zone” off Portugal — near the Azores. It generated a giant tsunami that went both directions, as far as Caribbean islands. It killed more than 100,000 people and destroyed the city of Lisbon. It sapped Portugal as a going concern — European power — impacting in grand scale not only the religious thinking of the time but philosophical constructs.

Salmyo, Portuguese for salmon. Some of those old salty dogs talked about fishing a river along the Spanish border — Rio Mino — for salmon.

Atlantic salmon.

For me, Pacific salmon, a calling in Salish. Words whispered by the prince and his salmon people, lured me away from that walkabout. We ended up as a family moving to Paris, France, and then Munich and Edinburgh. We harbored in Arizona, where I became, of all things, a dive master. Then, Mexico, Central America, Belize. West Texas, New Mexico.

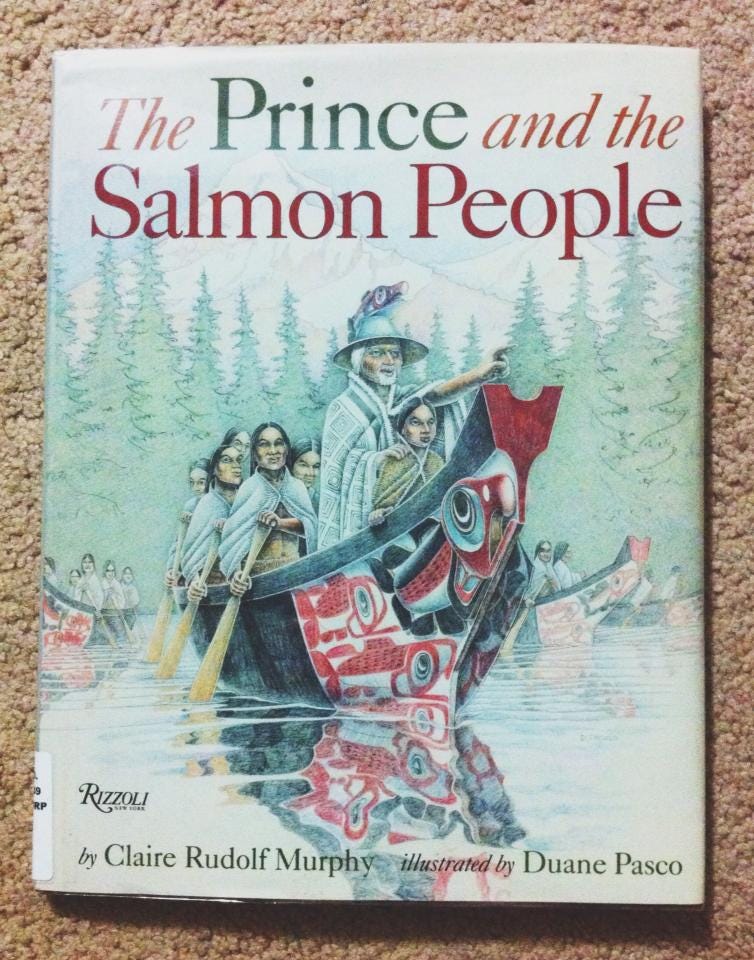

That home stream, that electromagnetic pull, got me to Spokane. I ended up working on a study guide for six through eight graders for Claire Rudolph Murphy’s Tsimshian tale, The Prince and the Salmon People.

I am here, in Vancouver, having traveled from Seattle via Spokane. I just finished work on two magazine pieces around the 70th Anniversary of Hanford, the Manhattan Project, also couched as the A-bomb. That was 2013. My pieces were on downwinders — those people throughout Washington, Idaho, Montana, California and Oregon hit with bursts or radioactive iodine 131. Secret government experiments during the cold war. Millions of gallons of radioactive waste in tanks buried along the Columbia.

The iodine 131 came with the winds and settled into feed, hay. The milk runs to Spokane from Pasco carried the radionuclide with them.

Stories of three-eyed salmon. Sheep born with two heads. My Nez Perce and Yakima Indian friends speak about young girls with cancers. Diseased thyroids for people in their twenties. Aches, pains, stomach ailments, early deaths. Stories of the Pacific Northwest, really, as those waters around Hanford leech into the mighty Columbia as it makes it way to the Pacific.

Salmon made me a storyteller. I have a sockeye tattooed on my right calf muscle. I listen to those sidebar stories. I listen to writers born in the Pacific Northwest. Born to tell the story of their own returned journey.

It’s a story etched in fossils a hundred million years old. Over and over, the stories, yet what is literacy unless we embrace the knowledge that rivers and streams have to be clean, unimpeded, free-flowing, and cold in order to harbor life, to make the salmon. To make warm-blooded storytellers.

David James Duncan:

To learn to live with the earth on the earth’s own terms is more important to me than literacy. I lived on the Oregon Coast at a time when the most ancient Sitka spruce groves in the world were being converted daily into the LA Sunday Times. There was, in my view, nothing in the Times’ stories of that era that compared in beauty or import to the trees that were slaughtered to create the newspapers. The news those trees were emitting was something invisible, called oxygen. The news those trees published constantly was keeping the planet alive. We killed them in the name of literacy.

The end

The Prince and the Salmon People Study Guide, Developed by Paul Haeder and Claire Rudolf Murphy

+—+

Jan. 1, 2025: We gather to hold the memories, hold the cycles of history and what future holds in the cupping hands of the past.

At the Yachats Commons, first, with the Yellow Bear Community drum used for the opening ceremony of the New Year’s Day Peace Hike, as well as other events. Chief Doc Slyter taught the white people — Joanne Kittler and Kinlen Wheeler how to honor and take care of the drum.

Yellow Bear isn’t a Native American Drum. Made by Dwight Lind as a personal ceremonial drum, it is close to the sacred — made from Alaskan yellow cedar with cedar, tobacco and eagle feather inside.

Low vibration, deep bringing to life chest penetrating sounds, for this day, and other days.

“The hike has been a collaboration, and it’s really grown. We had about 200 people taking part last year, and some 150 walked to the Amanda statue,” said Joanne Kittel, one of the trails committee leaders.

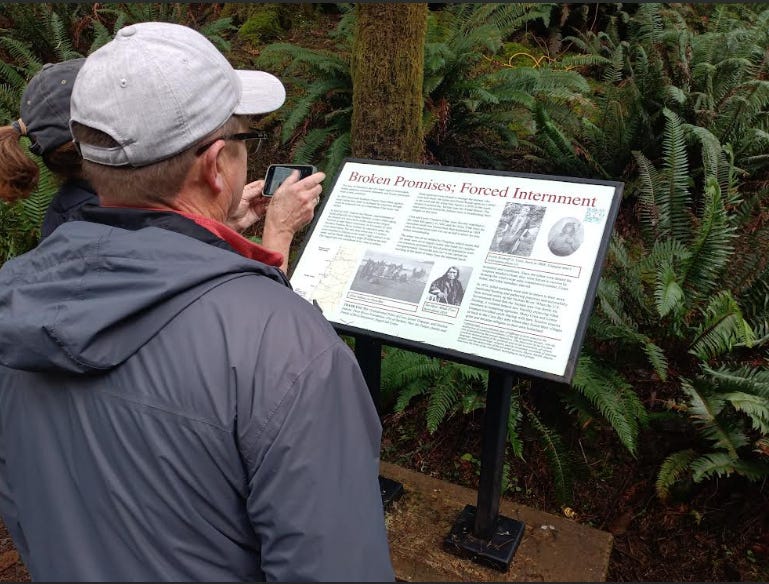

For so many years, the community didn’t know about the horrific treatment suffered by tribal members under government-sponsored genocidal policies during the 19th century.”

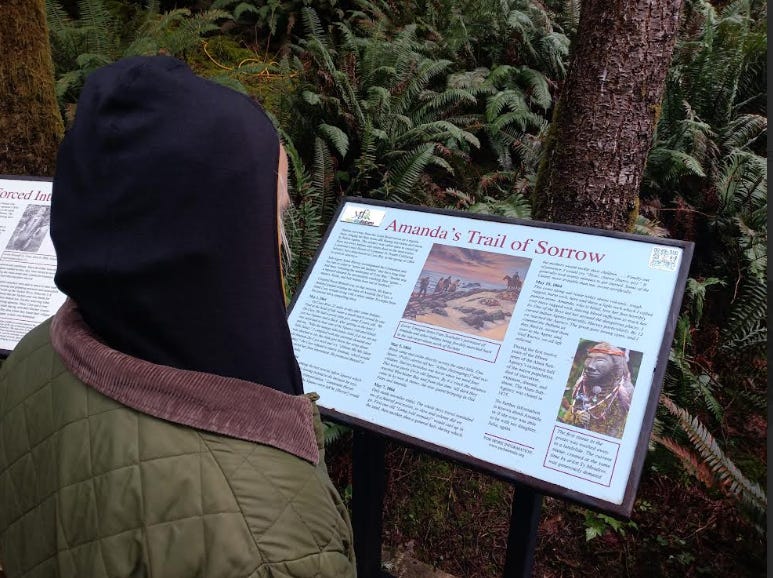

She urged people seeking more information to watch a video titled “The Amanda Story” available through this YouTube link. There is also a detailed Amanda’s Trail curriculum developed by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians available online here.

Today:

The statue is a tribute to Amanda De-Cuys. In 1864, the blind member of the Coos tribe was wrenched from her daughter and forced by government soldiers to walk barefoot to a prison camp in what is now Yachats. The photo of the flute player is of the now deceased Chief.

Participants received Peace Hike buttons, designed this year by artist Morgan Gaines, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians.

I was there on my own, my way of seeing this next and next chapter of my life in this chaotic and terror-filled world. I am lost, really, Man Lost of Tribe. I wore my read keffiyeh.

[Black & White – A black and white Keffiyeh are said to be associated with the Fatah – A former Palestinian National Liberation Movement, and a nationalist social-democratic political party that is the second biggest political party in the Legislative Council. Additionally, it is the biggest fraction of the allied multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization.

Red & White – The stitch work in the red and white Keffiyeh is believed to be connected with the Palestinian Marxists. Founded back in 1977, the sector is the largest sects that make up the Palestine Liberation Organization and the revolutionary socialist.

While these are mostly assumptions, and may or may not reflect the truth, but the truth of the matter is that Keffiyehs and Palestine go hand in hand. A passionate handiwork that is still made piece by piece in Palestine. While its impact has grown down a great deal since the mass production of Keffiyehs around the world. However, nothing matches the quality and detailing of a handmade Keffiyeh from Palestine. When you hold a Keffiyeh handmade in Palestine you will be able to feel the association that comes with the Keffiyeh, rather than getting another accessory that is mass-produced in China.]

I was the only one with keffiyeh, and only one person in the group acknowledged it.

Many young people speaking at the event made clear that learning the languages of these peoples forebearers has brought young people to know the power of words, of the deeper connection to a culture and people than simple translations into English.

Siletz Dee-ni Wee-ya’, which is a combination of all Athbaskan dialectic variant vocabularies spoken by several of the original reservation tribes.

“How are you doing?”

Is really, How is your heart today?

One river is called Ten Mile Creek, but the Native language calls it the Heart of the Water Rushing.

The drumming came, and the Fire Song, by Rainbow Bird (Rob Murtah) brought fire to our life, making it sacred. Then, the Healing Song, calling spirits of Healing.

This hike was heavy for me, very heavy, and, alas, here we are: Gaza put humanity on trial in 2024 – and we’ve got blood on our hands. In 2024, humanity has been stained by genocide in Gaza, war, and the climate crisis. And while signs of hope persist, the future is bleak.

Nothing was mentioned at this ceremony, about our brothers and sisters in Palestine undergoing the same treatment as Amanda and her people — genocide. Land theft. Raping and Maiming. Child kidnapping. Cultural cleansing.

But not exact. Massive tech war, surveillance, and of course, we see this real time on our fucking phones.

The little town’s new mayor, Jewish, Craig Berdie, mentioned NOTHING about the world at large, the deatha and dying caused by his people, his tribe. So fucking typical. So pathetic. So girdled by political incorrectness.

GIVE ME better people in the fucking world! In this episode, we sit down with a very special guest, Nick Estes, Lead Editor at Red Media. Nick is a Lakota activist, writer, and scholar whose work delves into settler-colonialism, indigenous history, and decolonization. He is the author of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance, now available in paperback with a new afterward through Haymarket Books. Nick has also been a vocal advocate for Palestinian liberation, highlighting the ongoing genocide in Gaza and exploring the intersection of the struggles faced by Palestinian and Indigenous peoples in America on the Red Nation podcast. Join us as we engage in a deep, thought-provoking conversation with Nick Estes, where we explore these critical issues and more.

+–+

How many times did Winona LaDuke tell me that the only way to heal, to move forward, from any paradigm of wicked intentions — from bloody conquest, to bloodless policy, to big oil-energy-chemical-pharma-ag-business of the upteenth degree — is to re-appropriate language, history, and story?

She knows about history being banned —

This morning, I am looking at one of the banned books, Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years. The book, originally published in 1991 by Milwaukee-based Rethinking Schools, is intended to provide educators with tools to re-evaluate “the social and ecological consequences of the Europeans’ arrival in 1492” and was written in time for the quincentenary. That was the event the Chicago Tribune had promised would be the “most stupendous international celebration in the history of notable celebrations.”

Perhaps a bit optimistic in retrospect. In the book, the question was asked, What were the consequences — both positive and negative –of this “discovery,” or, in actuality, the blind luck of some poor navigation skills. Apparently this book is the pinnacle of what should not be read.

Rethinking contains writings of many noted and national award-winning Native works, including Buffy Sainte-Marie’s My Country, ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying, Joseph Bruchac‘s A Friend of the Indians, Cornel Pewewardy’s A Barbie-Doll Pocahontas, M. Scott Momaday’sThe Delight Song of Tsoai-Talee, and others. As a side note, Sainte-Marie won an Academy Award, and Momaday won a Pulitzer Prize.

My essay “To the Women of the World: Our Future, Our Responsibility” was also included in the book. Interestingly enough, if I were going to ban one of my essays from a public school, this would probably not be the one. The essay is the transcript of my opening plenary address to the United Nations Conference on the Status of Women in 1995, held in Bejing, China. Other books and writings banned include those by famed Brazilian educator Paulo Friere and, in a multiracial censorship move, Shakespeare’s The Tempest was also banned.