environmental slavery, racism, and Judaic Supremists; The World According to the Eretz Israel!

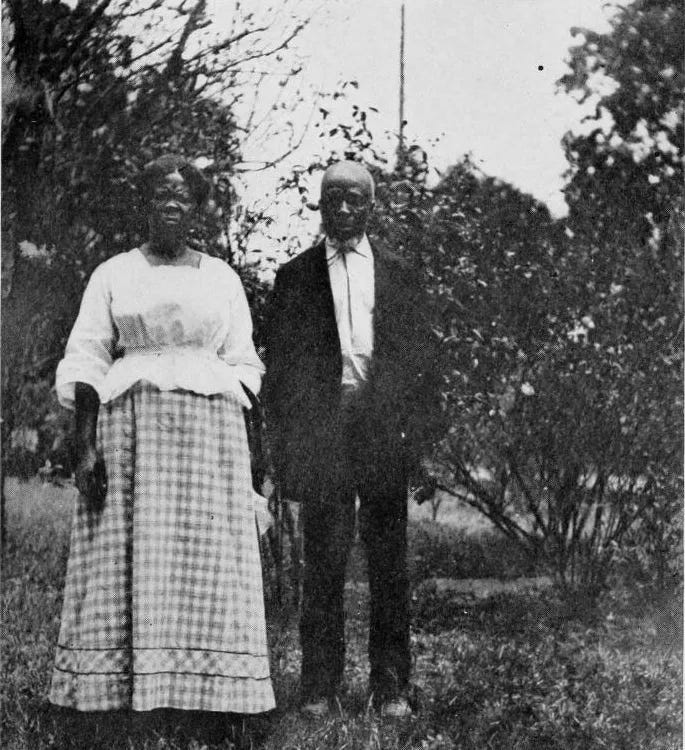

One hundred and sixty-four years ago, slave traders stole Lorna Gail Woods’ great-great grandfather from what is now Benin in West Africa. Her ancestor, Charlie Lewis, was brutally ripped from his homeland, along with 109 other Africans, and brought to Alabama on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States. Today, researchers confirmed that the remains of that vessel, long rumored to exist but elusive for decades, have been found along the Mobile River, near 12 Mile Island and just north of the Mobile Bay delta.

“The excitement and joy is overwhelming,” says Woods, in a voice trembling with emotion. She is 70 years old now. But she’s been hearing stories about her family history and the ship that tore them from their homeland since she was a child in Africatown, a small community just north of Mobile founded by the Clotilda’s survivors after the Civil War.

That slave ship. That illegal slave ship. That fucking Alabama Cheating and Lying White Dirty Family. That history of destroying the ship and going silent on its wehreabouts. That Alabama. That fucking place, but first, environmental racism, which is covered in the documentary, Descendent:

A little bit of Planning 101 for Africatown:

WALTER ISAACSON: I have been absolutely fascinated by the concept of environmental justice. Tell me what that concept means and how you became the father of that.

ROBERT BULLARD, AUTHOR AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCHOLAR: Well, environmental justice embraces the principle that all communities are entitled to equal protection of our housing, transportation, employment, and transportation energy. And so it’s a concept that’s rolled in equal protection, equal access, equal enforcement. And it’s not a fuzzy issue. It’s an issue of the right to live in a neighborhood that’s not overpolluted, a neighborhood where your kids can play outside on the playground that’s not next to a refinery or a chemical plant.

ISAACSON: And that’s how you got into it. It was 1978.

BULLARD: 1978. That was so long ago. And it was an accident. It was an accident. You know, my wife came home one day and said, Bob, I have just sued the state of Texas, and I have sued this company that’s trying to put this landfill in the middle of this suburban middle-class black community in Houston. And she said, I need somebody to collect data for this lawsuit and put the — where the pins are and where the landfills are on a map. And I said, well, you need a sociologist. She said, that’s what you are, right?

(LAUGHTER)

BULLARD: That’s how I got roped into this. I got drafted.

ISAACSON: And you discovered that there were like seven landfills. How many of those seven were in African-American neighborhoods?

BULLARD: Well, what I discovered, from the ’30s up until 1978, that five out of five of the city-owned landfills were in black neighborhoods. Six out of the eight of the city-owned incinerators were in black neighborhoods, and three out of four of the privately owned landfills were in black neighborhoods, even though blacks only made up 25 percent of the population during that period of time. And this is in a city that — it’s the fourth largest city and a city that doesn’t have zoning. So somebody was making these decisions. And what we found is that it was not random. Everybody produces garbage, but everybody doesn’t have to live next to the landfill. And it was not just a poverty thing. The subject of the lawsuit, Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management, was a middle-class black neighborhood of homeowners; 85 percent of the people owned their homes. And so it was not a poverty park. It was not a ghetto. This was a solid middle-class neighborhood of houses and people and trees.

ISAACSON: The City Council of Houston that’s making that decision back then, what’s the racial makeup of that city council?

BULLARD: All white.

ISAACSON: All seven?

BULLARD: All seven.

ISAACSON: Yes.

BULLARD: So you get this whole idea of environmental justice also means having access to decisions that are being made and making sure that there’s access, and that no one segment of our city or a county or region should be making decisions for other people. And so the idea that this was a policy of not having individuals on the City Council in that room saying, well, let’s not just put all the landfills or the incinerators or the garbage dump in this one area. And so it’s a matter of equity, a matter of fairness and a matter of civil rights.

ISAACSON: And how does climate change affect this?

BULLARD: Well, climate change — if you look at environmental justice, climate change basically overlays this whole issue of who has contributed most and who is going to be impacted the greatest. And if you look at the footprint of climate change — and climate change is more than parts per million and greenhouse gases. It also includes who is most vulnerable. Who is going to have the burden of living in these areas that are going to be hit hard, whether it’s droughts or there’s flooding or whether other kinds of issues. And, again, climate change, sea level rise will exacerbate the inequities that already exist. If people are poor, they’re in low-lying areas that’s prone to flooding, you’re going to get more flooding. You’re going to get more droughts and more disasters. You’re going to get more of issues of the widening gap between haves and have-nots. And you’re going to get this whole piling on effect of not having, you know, a level of resilience to bounce back because of a flood.

ISAACSON: So let’s be specific. You were here for Harvey, right? How many inches of rain did Harvey dump on Houston?

BULLARD: Fifty-two, 53, whatever. Nobody counted on that. I have worked on environmental justice and climate issues and disasters for 40 years, and working with other communities that have been forced to evacuate. I never had to be evacuated until Harvey. In this case, it was very unique for me and very unique for a lot of people, because, in some places, some neighborhoods, some areas had never flooded before.

ISAACSON: How did the city flood, white areas vs. black areas?

BULLARD: Well, if you look at the GIS maps, studies just came out last year showing that the communities that historically that have flooded over a period of time — we’re not talking major storms. We’re talking mostly African-American, Latino areas in terms of the East Side. Divide the city in half. Harvey basically followed that pattern. Even though a large part of the city flooded, the areas that got hit the hardest are the areas that historically have always gotten hit hard.

ISAACSON: Houston is famous for not having many zoning laws. How does that affect things?

BULLARD: Well, as a matter of fact, Houston is a no-zoning city, and it’s very proud of that. It’s unrestrained capitalism. And it means that, historically, it’s the only residential protection land use device is with deed — renewable deed restrictions. But the fact is that we have a lot of our land uses that’s willy-nilly, a lot of building that’s in areas that we probably shouldn’t be building in. And the idea of, how do we make corrective action that’s happened over the last 50, 75 years, it’s hard to do that now. So that means that we have to come up with sensible planning. We have to talk about how we’re going to, in some cases, probably restrict the kinds of development that most cases would be dictated by money, as opposed to some common sense. And so–

ISAACSON: Wait. Give me an example of that.

BULLARD: Well, in terms of a lot of the houses that flooded on the western part of the city were built right up to the reservoirs. And — Addicks, Barker reservoirs. And these — and those houses, we’re not talking low-income, middle-income. We’re talking very well-heeled families, million-dollar, $2 million homes that were built in a floodplain and that were built in the areas that, with an event like Harvey, is bound to flood. And you talk about what it means to provide protection, not just for well- heeled communities, and the idea that, if we can provide the kinds of flood protection and flood mitigation and the kinds of restructuring of our land uses, and allow for some communities to somehow relocate, it has to be a plan that brings a lot of communities to the table. And, historically, Houston has not been a city that has been diverse when it comes to decision-making. It’s been mostly a top-down. And so I think Harvey has brought a lot of rethinking of what that means.

ISAACSON: Has Harvey brought people of different socioeconomic and racial groups together?

BULLARD: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. But you have to look at it and say, it took a biblical flood to bring a lot of the groups and organizations that generally had not worked together on a lot of issues, organizations that work on wetlands and on prairie issues, issues of environment, pollution, industry, transportation. It brought a lot of groups together. We came — almost three dozen groups came together and decided that we need to be talking, we need to be working together. And we came up with this organization named the Coalition for Environment, Equity and Resilience, CEER. And, again, the heart of that whole thinking is an equity lens. And one of the first things we did is, we came together and came up with this framework. And we presented the framework, equity framework, to the county, Harris County. And they basically adopted this whole idea that future development and future funding of projects dealing with Harvey or flood mitigation or going forward must be looked at through an equity lens.

ISAACSON: Houston, how segregated is it racially and economically?

BULLARD: Well, you know, Houston is still segregated. It’s segregated by race, and it’s also segregated by income. And, again, if you look at this whole idea of concentration of white affluent census tracks, or zip codes, you can see that increasing. You can also see the increasing numbers of low-income families, families of color, concentrated in those census tracks, in those areas.

ISAACSON: Wait. Wait. So you’re saying it’s becoming more segregated?

BULLARD: More income-segregated.

ISAACSON: Why?

BULLARD: Well, that’s a big question of the day. And it’s not just a Houston question. We are becoming more and more separate and apart by income. And affluent people feel more comfortable living with affluent people. And, oftentimes, poor people don’t have a choice but live around poor people. And housing choices oftentimes will dictate where people live. And the fact is that Houston and most major cities in this country have a housing affordability issue. And if you have to drive to qualify, which means drive long distances to qualify for housing in terms of ownership, that means that the housing that’s available, people have to settle for less. And more and more people are settling in those areas where they can afford. That means that you’re having more and more concentrated areas with people of color, as well as poor people. Now, that’s not the best way to create healthy, livable, sustainable, resilient cities, but that’s what we get when we let market forces drive it, as opposed to trying to assist and support a sane program of creating more, what — what do they call it, mixed income housing and mixed use.

ISAACSON: Right.

BULLARD: I will tell you another thing. It’s not just the housing being segregated. So is pollution. Pollution is segregated, which means that, as you start getting more and more low-income families and families of color concentrated in areas where there’s lots of pollution, more and more pollution gets put in those areas. And so you get the segregation of income and race, but you also get the income of pollution. And that’s where we say — you know, I wrote a book on this called “The Wrong Complexion for Protection.” And it means that — and I’m not just talking about race. It’s also income. Middle-income African-Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods — when I say middle income, I’m talking $50,000 to $60,000 — are more likely to live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than whites who make $10,000. You say, how can that be? It means that there is a racial and economic dynamic in housing that allow low-income whites to move into middle-income areas and to exit polluted neighborhoods, whereas institutional racism will keep black families, middle-income, in those neighborhoods.

ISAACSON: After Katrina, we all realized in New Orleans we were in the same boat, and it did bring us together some. And we did rebuild the Lower Ninth Ward, but there was more of an integration of the city. Do you think environmental catastrophes like Harvey will start doing that in places like Houston, make people realize we’re all in the same boat?

BULLARD: Well, you know, I hope we don’t have to wait for a disaster. But it did. And the kinds of — in some cases, these wakeup calls oftentimes are the only thing that will wake us up, and to a reality that — I have a saying, that when we don’t protect the least in our society, we place everybody at risk. We don’t strengthen the levees or we don’t provide flood protection for one segment, we place everybody at risk. When we don’t provide protection in terms of immunization or whatever, then it will place everybody at risk. And so it seems to me that a justice frame, an equity frame should be the logical framework to accept. But, you know, we are a hard-headed society.

(LAUGHTER)

BULLARD: It’s almost like we need a two-by-four to hit us over the head and wake us up and say, aha. And we need those aha moments before disasters hit. But I do think that Houston post-Harvey is a different Houston in terms of thinking, in terms of mind-sets, in terms of thinking about this whole idea that we are a big city, and that we can’t just somehow have communities that are invisible. I wrote a book in 1987 called “Invisible Houston.” Houston in 1987 had the largest African-American population of any city in the South. There were over a half-million black people in Houston, more people than in Atlanta or New Orleans. And so the idea that, even though you had this large black population, the black community was invisible when it came to landfills, incinerators, was invisible when it came to economic development, providing the kinds of growth and planning that will build communities that was — that had those things. Middle-income African-American communities in Houston didn’t have the same kind of amenities as the low-income white communities. So the idea that invisible, that invisibility must be erased, and we must make all communities visible, so that they can join in this new green energy economy and post-disaster to talk about building resilience. There has — you know, when we talk about climate, we talk about climate justice. When we talk about the environment, we talk about environmental justice. When we talk about energy, we talk about energy justice. All these things, when you look at the justice framework, it can apply to almost all the aspects when we talk about issues around sustainability.

ISAACSON: In Houston, and to some extent in all of Texas, the energy industry just doesn’t even like to utter the words climate change. Is it possible to move towards environmental justice without confronting climate change head on?

BULLARD: No, it’s impossible. When we talk about climate change and we talk about environmental justice, when we start connecting, you know, the tissue of climate responsibility and the issue around vulnerability, you can’t get around solutions, real solutions, without talking about justice inequity. That’s why the climate justice frame is a frame that, as I said, is more than just looking at greenhouse gases in parts per million. It brings in the issue of which communities are vulnerable, which communities have contributed least to the crisis, but are feeling the pain right now, first, worst, and longest. That’s true here in Houston. It’s also true in Texas. It’s also true in the United States and globally, this whole issue of vulnerability and the whole issue of, how can we make sure that our plans do not further marginalize already vulnerable populations by creating plans that somehow exacerbate that vulnerability and create more problems for that — quote — “invisible group,” the group that may not necessarily be in the room when they’re deciding what to build and where to spend moneys. That’s the justice part. And even though the state of Texas may not recognize climate change as a concept, the whole issue of vulnerability and the whole issue of severe weather events, you look at the map, and there’s no way for the state not to look at where the hot spots are and where the solutions need to be, where the mitigation and the adaptation will have to occur, no matter whether they believe in it or not. And that’s why I tell people, I said, believing in climate change is not — it’s not the issue. It’s like asking somebody, do you believe in gravity? And it’s not — believing in gravity is not — is not an issue. If you climb up a 50-story building and jump out, gravity will kick in. And so whether you believe it or not, it’s real.

ISAACSON: Dr. Bullard, thank you so very much.

BULLARD: My pleasure. My pleasure. Thank you.

Environmental Racism — Public Health Resources for Understanding Environmental Racism [Wisconsin Chapter]

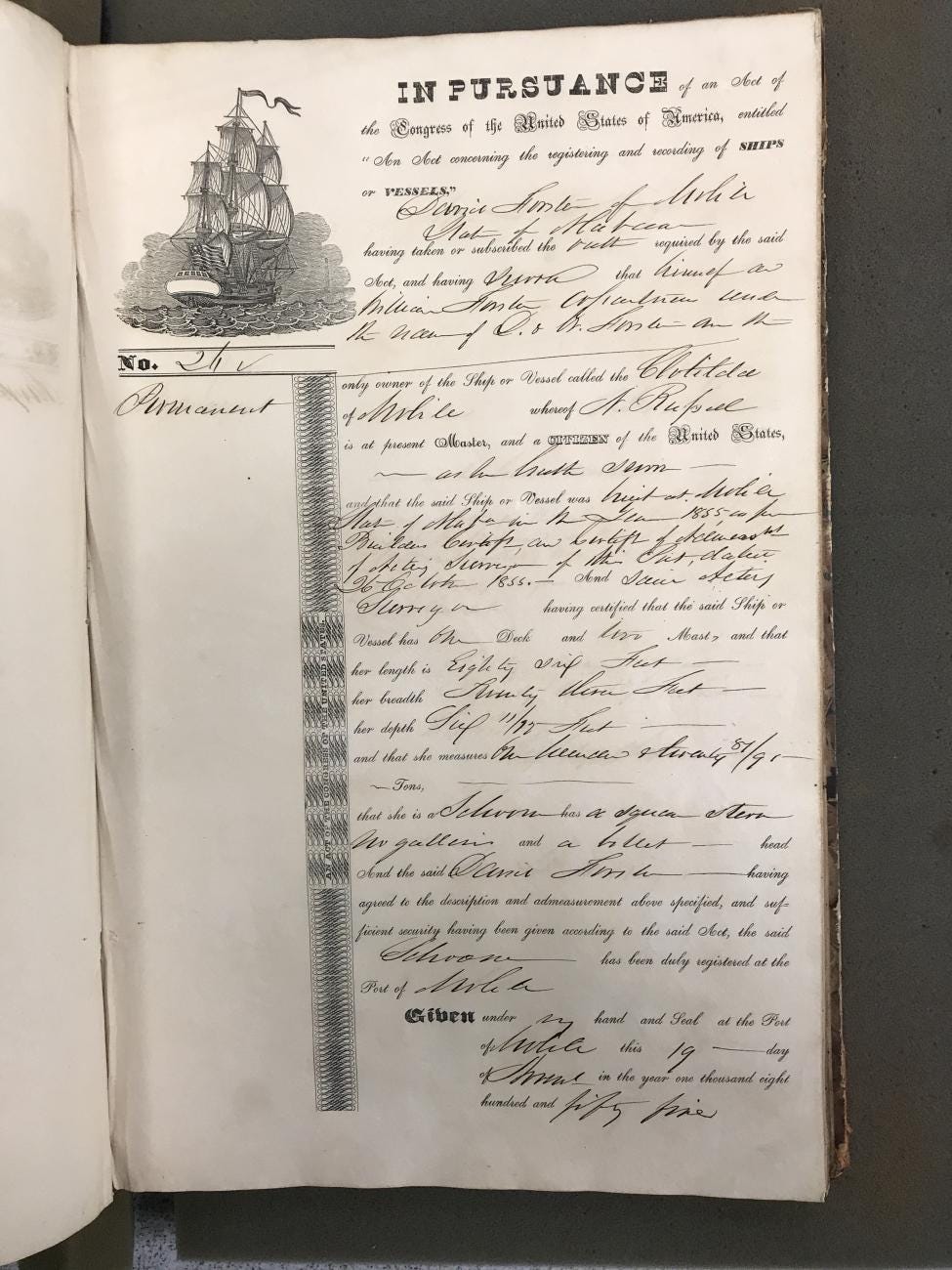

Historians feared the last known documented slave ship to force enslaved people of African descent to the United States had been forever lost. After all, historical accounts of the slave ship Clotilda ended with its owners torching the 86-foot schooner down to its hull and burying it at the bottom of Alabama’s Mobile Bay. Then, earlier this year, researchers aided by NMAAHC recovered remnants of the Clotilda and, in doing so, expanded our understanding of our American story as part of a bigger human story.

Through the Slave Wrecks Project (SWP), an international network of institutions and researchers hosted by NMAAHC, the Museum has ventured well beyond its walls to search for and find slave shipwrecks around the globe. Shipwrecks have been found off the shores of such countries as South Africa, Mozambique, Senegal, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

When the slave ship Clotilda arrived in the United States in 1860, it marked the persistence of the practice of cruel forced migration of people from Africa: Congress had outlawed the international slave trade more than 50 years before. The ship docked off the shore of Mobile, Alabama, at night to escape the eyes of law enforcement and deposited 110 men, women, and children stolen away from their homeland in modern-day Benin. The ship’s arrival on the cusp of the Civil War is a testament to slavery’s legal presence in America until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. After the war, people who had been held captive aboard the ship helped found the community of Africatown, a community that exists to this day.

Alabama Historical Commission

Last year, NMAAHC and SWP joined researchers and archaeologists from the Alabama Historical Commission and SEARCH, Inc., in pursuit of the ship and its history. They scoured the turbulent waters of Alabama’s Mobile River where they located a wrecked ship that matched the dimensions of the Clotilda. Divers were dispatched to collect debris fragments like iron fasteners and wooden planks that were compared against construction details in Clotilda’s registration documents. And in May, after a year of research, scholars reached a confident conclusion: the Clotilda had been positively identified.

SEARCH, Inc.

For residents of Africatown, the close-knit community founded by people previously enslaved on the Clotilda, the discovery carries a deeply personal significance. SWP particularly focused on making sure the community of Africatown, Alabama, was central to the process of recovering the history and memory, and invited residents and descendants to share their reflections on the importance of this discovery.

While we can find artifacts and archival records, the human connection to the history helps us engage with this American story in a compelling way. The legacies of slavery are still apparent in the community. But the spirit of resistance among the African men, women, and children who arrived on the Clotilda lives on in the descendant community in Africatown.

Mary N. Elliott

Curator of American slavery at NMAAHC and leader of the community engagement activities for SWP

Alabama Historical Society

In 2015, SWP helped recover remnants from the slave ship São José off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa, providing the first archaeological documentation of a vessel lost at sea while transporting slaves. You can view artifacts from the São José in the Museum’s Slavery and Freedom exhibition and in our stunningly illustrated book, From No Return: The 221-Year Journey of the Slave Ship São José.

Susanna Pershern, U.S. National Parks Service

159 years after its sinking, the Clotilda’s recovery and SWP’s continuing work around the world represent the vital role of the Museum in uncovering facets of our American story that have yet to be told. With the support of our community, we actively pursue new information that expands the way people around the world understand the American story.

The Slave Wrecks Project is one of the things I’m most proud of… It’s really about recognizing that the slave trade is not about yesterday. It’s as much about today and tomorrow… Lonnie Bunch III, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and Founding Director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

+—+

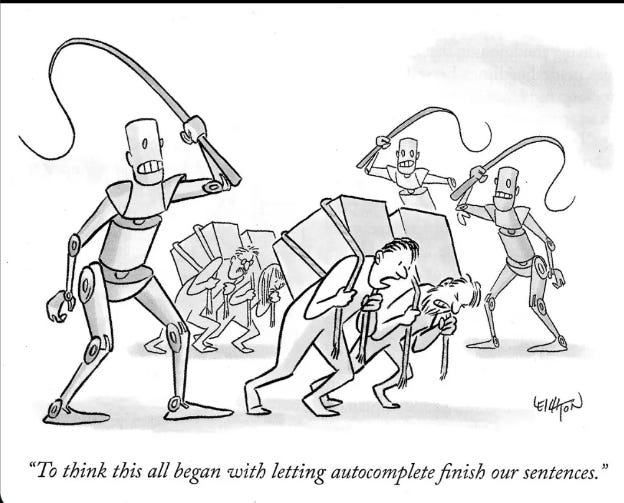

This is part 1 of an interview conducted by Jason Bosch in Philadelphia, PA on May 17, 2020.

• Part 1: The Fourth Industrial Revolut…

• Part 2: The Fourth Industrial Revolut…

• Part 3: The Fourth Industrial Revolut…

• Part 4: The Fourth Industrial Revolut…

• Part 5: The Fourth Industrial Revolut…

Full Playlist: The Fourth Industrial Revolution and …

+—+

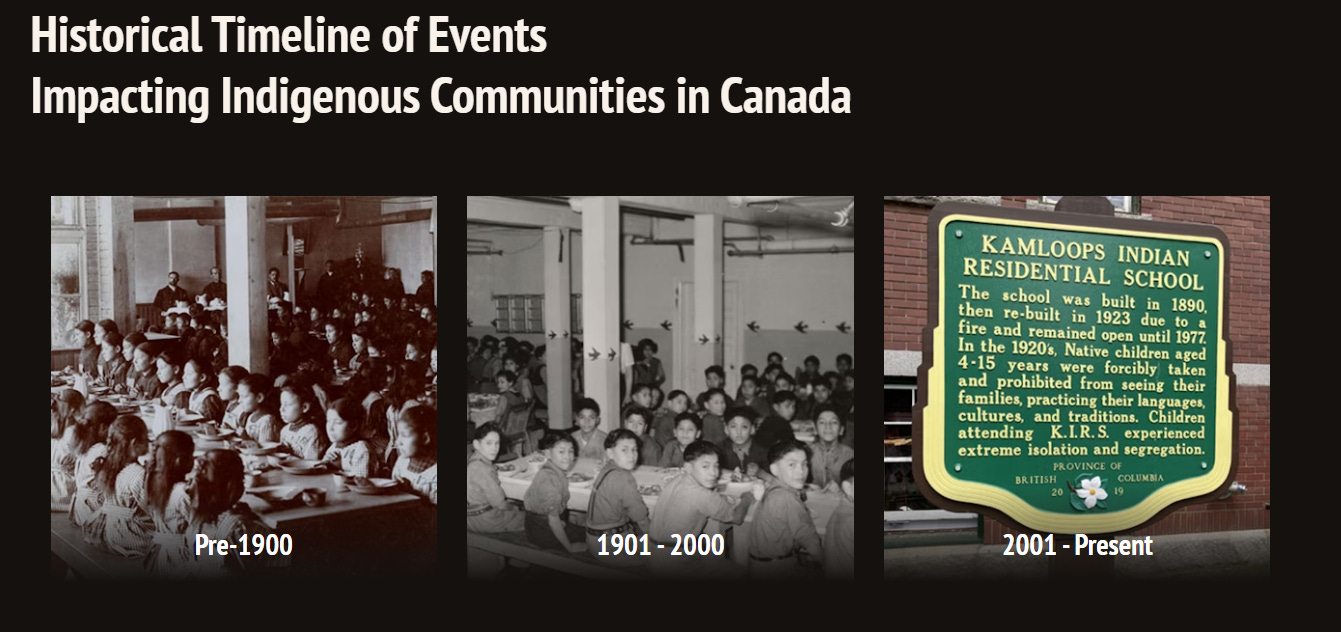

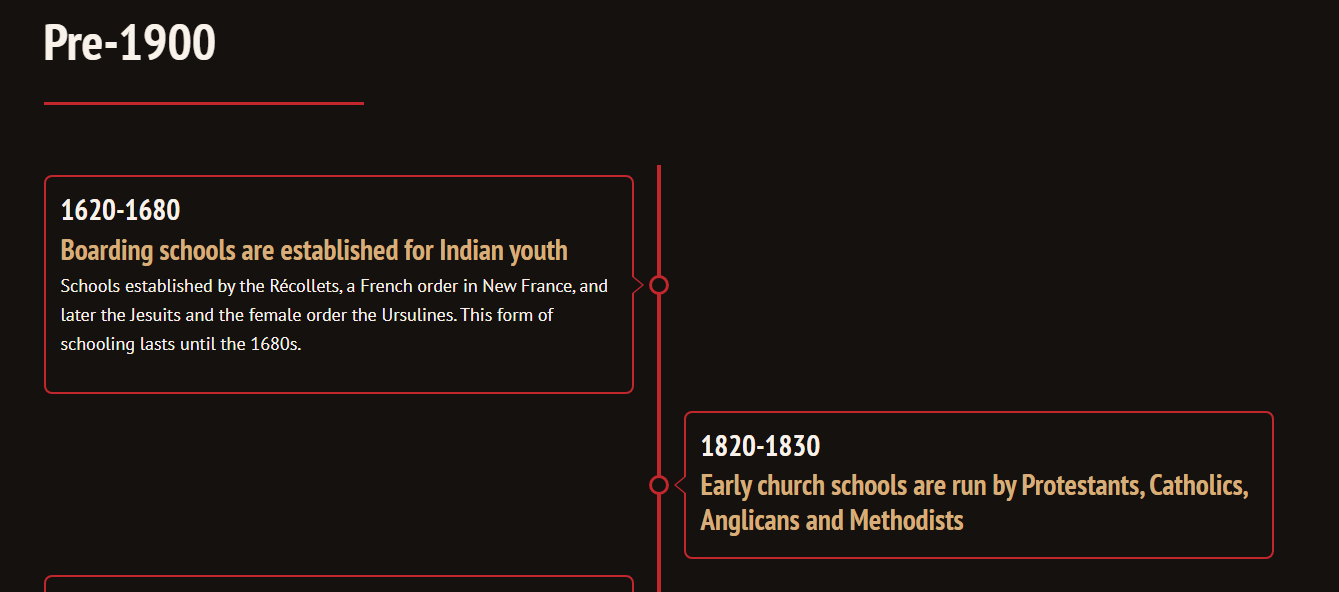

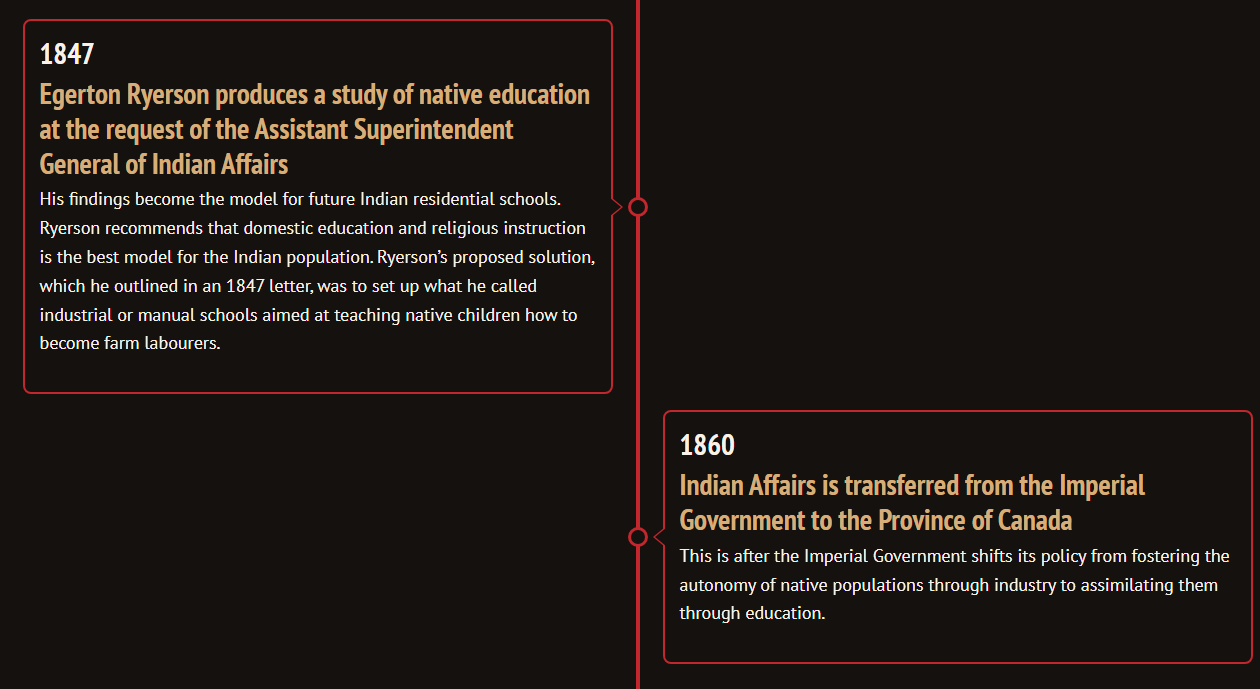

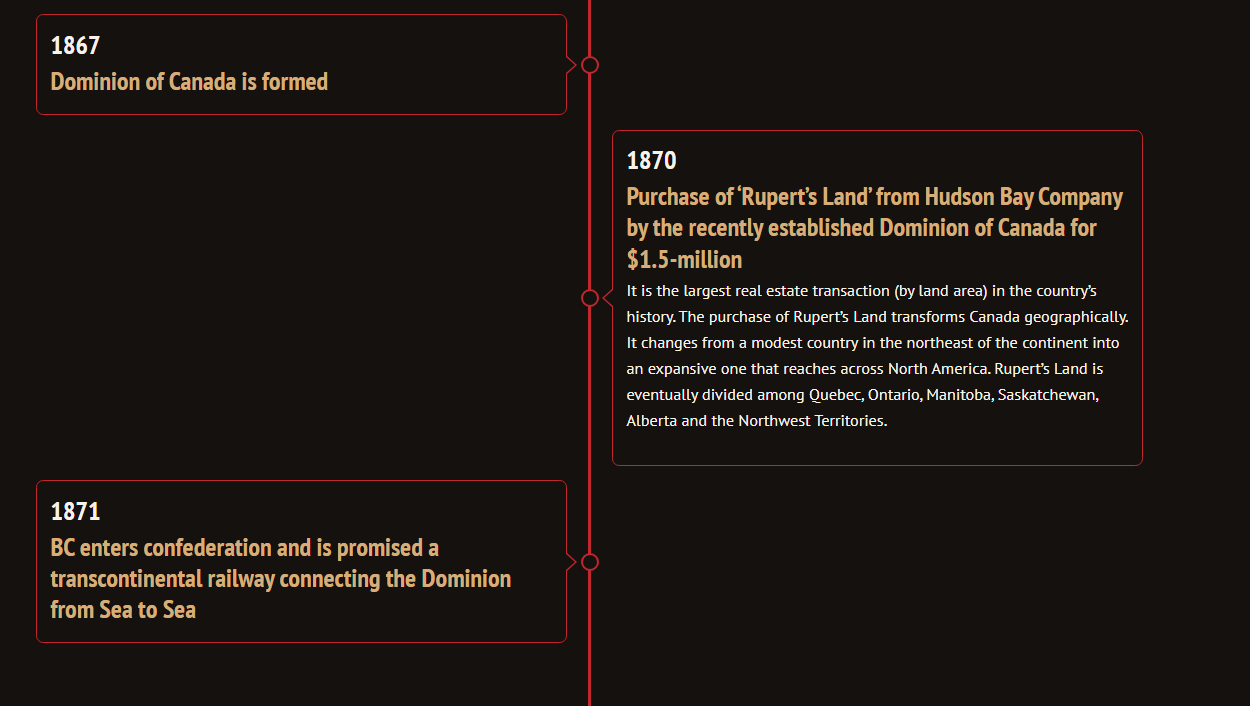

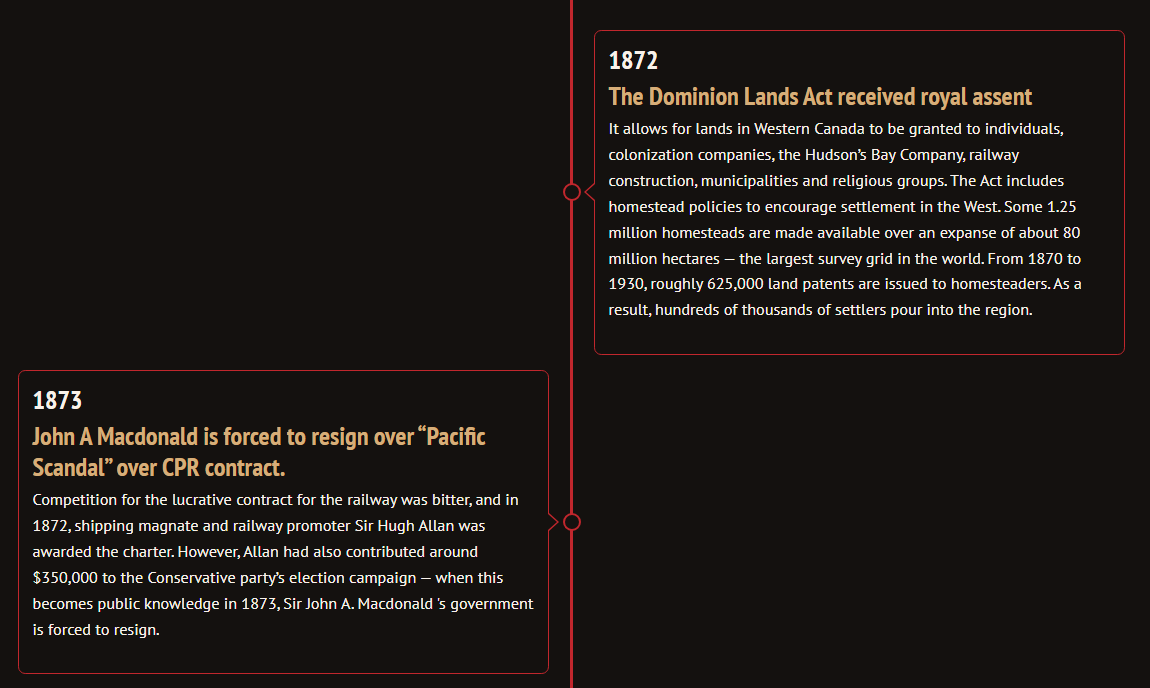

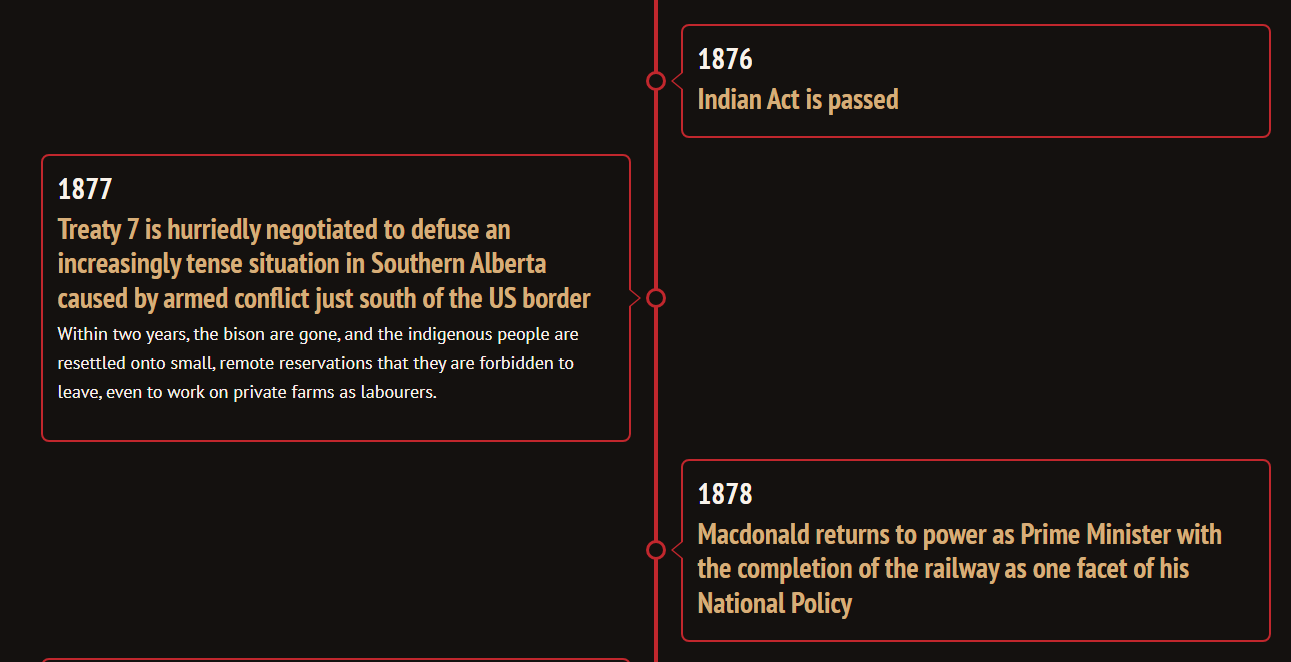

Historical Timeline of Events Impacting Indigenous Communities in Canada/ Pre-1900

+—+

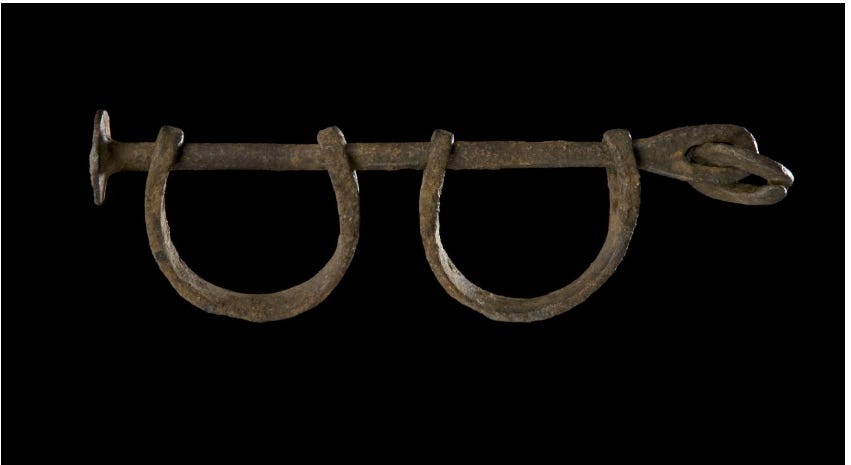

Ahh, the ebb and flow of this slavery “thing,” these block chains as real chains. Listen to him above.

+—+

About the Film

Bones of Crows is a multi-generational epic and story of resilience told through the eyes of Cree Matriarch Aline Spears (played throughout her life by Summer Testawich; Grace Dove, Monkey Beach; and Carla Rae, Rutherford Falls). Removed from their family home and forced into Canada’s residential school system, young musical prodigy Aline and her siblings are plunged into a struggle for survival. Over the next hundred years, Aline and her descendants fight against systemic starvation, racism and sexual abuse—and to build a more just future.

In the face of a rapidly shifting and hostile world, Aline’s remarkable journey moves through memories of residential school, perilous adventures across snowy traplines and classified London bureaus, where she works as a code talker in the Second World War. Supported by her daughter Taylor, a determined lawyer, and granddaughter Percy, the family’s creative force, Aline must find the strength to step into her role as family Matriarch and confront the scars of the past.

A sweeping drama grounded in historical truth, Bones of Crows weaves together underrepresented moments in Canadian and Indigenous history, including the Indigenous contributions to WW2, the ongoing cases of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Aline’s story enriches our understanding of the past and empowers us to address our collective future.

+—+

Oh, those Anglo-Saxon-Francos. Oh, the rapes, infanticide, the nuns, the clerics, the priests and the deacons, and the fucking sick Catholicism.

There are no values to First Nations people in their fucking minds.

A long time ago? NOW.

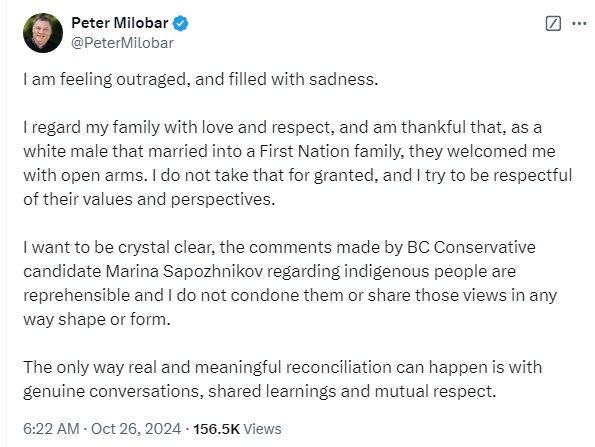

Oct. 29, 2024: During a news conference on Oct. 29, following the final election results, Conservative Leader John Rustad said Marina Sapozhnikov will not be a candidate for the Conservative Party of B.C. moving forward. Rustad called her comments offensive and said they do not represent him or the party.

A FUCKING Ukrainian, just on track with her racism.

A B.C. Conservative candidate has come under heavy criticism for making derogatory comments about Indigenous people during an election-night interview, sparking widespread condemnation and calls for her removal from the party.

Marina Sapozhnikov’s remarks, initially reported by the Vancouver Sun, included calling Indigenous people “savages” and condemning Indigenous history courses taught in B.C. universities.

Her comments were made during an Oct. 19 interview with Vancouver Island University student Alyona Latsinnik, who later shared the recording with CBC News. In the tape, Sapozhnikov can be heard saying that Indigenous people “were savages” who “fought with each other all the time.”

She also goes on to denounce the NDP government’s adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, claiming it has turned non-Indigenous British Columbians into “second-rate citizens.”

The interview was part of a class assignment, said Latsinnik, an undergraduate student who is majoring in Indigenous studies and taking a journalism class for her minor.

She called the remarks “entirely unexpected.”

“Marina asked me what I’m taking and I told her, and then it all sort of spiralled from there,” Latsinnik told CBC News.

“I never expected anything like that to be said, especially from someone who is running for political office and knows she’s being recorded.”

The VIU student said she made efforts to counter Sapozhnikov’s statements during their interview, and that the experience left her deeply unsettled, describing it as “awful” and “bizarre.”

Latsinnik also reflected on the implications of Sapozhnikov’s comments.

“Unfortunately, comments like this set us back a hundred, 200 years from the progress we’ve made.”

She said she believes that many who supported Sapozhnikov might have reconsidered their choice if they knew about her views.

+—+

Undocumented? When the Canadian First Nations signed up in the Canadian military and worked as code talkers, when the war was done, they were not considered Original People’s. Now:

Children would have to show proof of U.S. citizenship or legal immigration status to enroll in a public school under new rules proposed by the Oklahoma Department of Education, a practice that could run afoul of federal law and deter children who are undocumented or from mixed-status families from attending school.

The agency’s proposal states that students without documentation would not be prohibited from enrolling. Supreme Court precedent requires public schools to enroll children living within their districts, whether they are in the country legally or not.

But federal law also bars schools from asking about a student’s citizenship or immigration status to confirm they live in the district as it can have a chilling effect on student enrollment, according to guidance to the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Education. Neither can schools discourage students from enrolling if they don’t have a birth certificate or if they have a foreign birth certificate.

[The face of a fucked up Goyim Zionist Pushing to have his fucking Jesus Fucking Military Christ in schools.]

The bill pushes the date of the debt ceiling out two years to Jan. 30, 2027, allowing more borrowing for two years.

“Now we can Make America Great Again, very quickly, which is what the People gave us a mandate to accomplish.”

The president-elect urged Republicans and Democrats alike to vote “yes” on the bill tonight.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-NY, said “hell no” to the deal.

“The Musk-Johnson proposal is not serious. It’s laughable. Extreme MAGA Republicans are driving us to a government shutdown,” he told reporters.

We are all ON the reservation now —

Israel has annexed the Al-Wahda dam in the basin of the Yarmouk river, close to the city of Al-Qusayr in the Dara’a governorate, and near the Jordanian border. This dam provides at least 30% of Syria’s water and 40% of Jordan’s water.

Everything is so predictable: what the NATOstan/Israel combo really wants is an amputated, disaggregated, vulnerable Syria. — Anarchy in the Levant

Silvia Federici is an Italian and American scholar, teacher, and activist from the radical autonomist feminist Marxist and anarchist tradition. She is a professor emerita and Teaching Fellow at Hofstra University, where she was a social science professor. She worked as a teacher in Nigeria for many years, is also the co-founder of the Committee for Academic Freedom in Africa, and is a member of the Midnight Notes Collective. Among her many books are Caliban and the Witch, Revolution at Point Zero, and Patriarchy of the Wage.

LikeLike