dirty dirty Yanquis and dirty dirty Brits — a fucking inbred love story that has taken the globe by viral Storm — talk about a spiritual and intellectual pandemic = AngloAmericanus!

Gaza, Sudan, Afghanistan, Ireland — the great manufactured genocides of hunger and stripping the food away!!!!!

Mexico’s Saint Patrick’s Day & Britain’s Genocide

By Paul Haeder (not probably going into the local rag, because . . . . You Figure it OUT!)

The history of Irish-American defenders of Mexico and the Catholic faith unfolded elegantly for me when I was living and working in El Paso and later in Mexico.

I have Irish roots, with family who ended up in Scotland and then Canada. That’s my Kirk side. While Ireland never held an allure for me, when I was there, including in Belfast, I dove into my history and realized how dirt poor and superstitious many of my brethren were.

But this? Every March 17 is celebrated with bagpipes and parades in Mexico! The irony of ironies is I even partied hearty in Chihuahua and Juarez on many a St. Patrick’s Day.

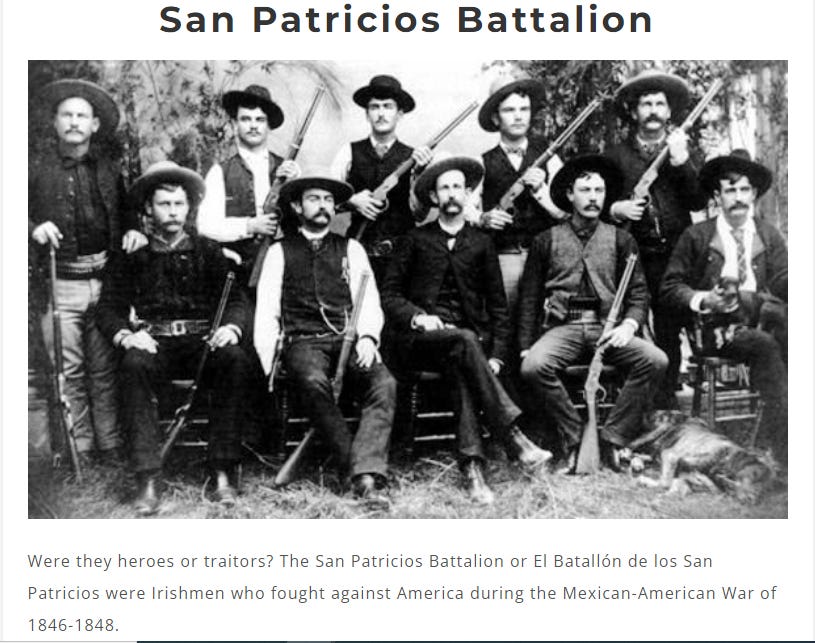

“Every St Patrick’s Day, the first toast that I make is in honor of the San Patricios,” says Martin Paredes, a Mexican writer based in the US. “A group of Irishmen came to the defense of Mexico, and many of them died in defense of Mexico. That has to be lauded as one of the greatest honors ever, because they were fighting for an adopted nation — and they died for an adopted nation.”

It is a complex story that goes back into the history of the Mexican-American war, for which most of my K12 and college students have no knowledge.

Paredes has written extensively on the San Patricio Battalion; Smithsonian Magazine has featured this history. The San Patricio Battalion was a military unit composed mainly of Irish soldiers that were serving in the US Army when the US was invading Mexico.

“These were US soldiers that left US lines and joined Mexican lines and fought for Mexico against the United States.” It was in a time when Texans were going after Mexicans and wanting that “independent state” to be annexed by the USA. War drums precipitated pressing men into the military to go fight against Mexico. Irish were considered non-people, and anti-Catholicism was rampant in the US.

Genocide: The touchstone for Irish folk is Ireland’s Great “Potato” Famine, which generated a huge wave of immigrants arriving to the US’s soil. During the peak of Irish emigration — 1845-1852 — nearly two million people – about a quarter of the population – emigrated to the United States.

Even this story is broken: According to economist Cormac O’ Grada, more than 26 million bushels of grain were exported from Ireland to England in 1845, a “famine” year. Even greater exports are documented. In the 1997 issue of History Ireland by Christine Kinealy of the University of Liverpool, her research shows that nearly 4,000 vessels carrying food left Ireland for ports in England during “Black ’47” while 400,000 Irish men, women and children died of starvation.

The food was shipped from ports in some of the worst famine-stricken areas of Ireland, and British regiments guarded the ports and granaries to guarantee British merchants and absentee landlords their “free-market” profits.

During the famine, the British government “deliberately and systematically adopted reckless and wanton policies of official neglect that exacerbated the famine’s savagery and substantially increased its cruel death count.”

Viva Mexico: Irish deserters from the US Army formed the core of the “Battalion of Foreigners,” which was renamed “Batallón de San Patricio.” Roman Catholic deserters from Germany and other European nations also joined, as did some foreign residents of Mexico City. There were also several African Americans who had escaped from slavery.

John Riley, a Galway-born soldier who was serving in the 5th US Infantry Regiment, led this battalion. Under Riley, this elite artillery-unit-turned-infantry battalion fought with distinction in most of the major battles of the war until the Battle of Churubusco (Mexico City) on August 20, 1847.

The unit was overrun, dozens of the San Patricios were captured, and many were hanged on the spot.

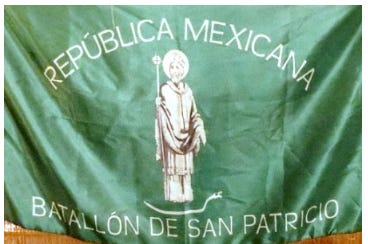

My El Paso friend Tom Connolly showed me his San Patricio banner of green silk. On one side is a harp, surrounded by the Mexican coat of arms, with a scroll on which is painted, ‘‘Libertad por la Republica de Mexicana.” Under the harp, is the motto “Erin go Bragh.”

On the other side is a painting St. Patrick. In his left hand is a key and in his right a crook of staff resting upon a serpent. Underneath is the name: San Patricio.

While in Mexico City years ago, I sought out the plaque bearing names of those San Patricios who died in battle, with an inscription of gratitude. They are considered martyrs who gave their lives during an unjust invasion. In Plaza San Jacinto stands a bust of Riley.

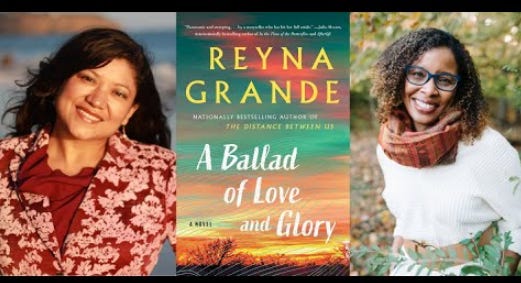

This Saint Pat’s Day read the novel, “A Ballad of Love and Glory” by award-winning writer and memoirist, Reyna Grande. It weaves a love story into the true tale of the San Patricios. Toast, drink a whiskey and listen to legendary Irish group The Chieftains and Ry Cooder on their album titled, “San Patricio.”

Check it out: THE IRISH FAMINE: COMPLICITY IN MURDER/ September 26, 1997

In his Sept. 17 op-ed piece, “Ireland’s Famine Wasn’t Genocide,” Yale economics professor Timothy W. Guinnane says, “With the potato crop ruined, Ireland simply did not have enough food to feed her people.”

According to economist Cormac O’ Grada, more than 26 million bushels of grain were exported from Ireland to England in 1845, a “famine” year. Even greater exports are documented in the Spring 1997 issue of History Ireland by Christine Kinealy of the University of Liverpool. Her research shows that nearly 4,000 vessels carrying food left Ireland for ports in England during “Black ’47” while 400,000 Irish men, women and children died of starvation.

Shipping records indicate that 9,992 Irish calves were exported to England during 1847, a 33 percent increase from the previous year. At the same time, more than 4,000 horses and ponies were exported. In fact, the export of all livestock from Ireland to England increased during the famine except for pigs. However, the export of ham and bacon did increase. Other exports from Ireland during the “famine” included peas, beans, onions, rabbits, salmon, oysters, herring, lard, honey and even potatoes.

[There has been considerable debate among historians and public commentators about whether or not the Great Irish Famine (1845–1851) could be considered as genocide. Recently, controversial journalist Tim Pat Coogan has argued that England’s treatment of Ireland in this period can be considered genocide. Historical evidence suggests otherwise. There was considerable blame for the perpetration of Ireland misery beyond the ill conceived and poorly executed policies of successive British governments. At the root of the famine tragedy was an outmoded and poorly functioning landholding system and over-dependence of an impoverished rural underclass on the potato staple. Anglo-Irish landlords, merchants, businessmen of all denominations, large landholding farmers, nationalist politicians, clergy, ineffective implementation of poor relief by local gentry, and unscrupulous port officials and ship’s captains must also bear some responsibility in contributing to this calamity in modern Irish history.]

Dr. Kinealy’s research also shows that 1,336,220 gallons of grain-derived alcohol were exported from Ireland to England during the first nine months of 1847. In addition, a phenomenal 822,681 gallons of butter left starving Ireland for tables in England during the same period. If the figures for the other three months were comparable, more than 1 million gallons of butter were exported during the worst year of mass starvation in Ireland.

The food was shipped from ports in some of the worst famine-stricken areas of Ireland, and British regiments guarded the ports and graineries to guarantee British merchants and absentee landlords their “free-market” profits.

Mr. Guinnane says that “the contrast with the Holocaust is instructive” and points out that the British did not act like Nazis who “devoted considerable resources to hunting down and murdering the Jews.” Instead, he says that “the British government’s indifference to the famine helped cause thousands of needless deaths.”

Richard L. Rubenstein, in his book, “The Age of Triage: Fear and Hope in an Overcrowded World,” says,

“a government is as responsible for a genocidal policy when its officials accept mass death as the necessary cost of implementing their policies as when they pursue genocide as an end in itself.” — JAMES MULLIN President Irish Famine Curriculum Committee and Education Fund, Inc. Moorestown, N.J.

Timothy Guinnane’s question, “But does the {British} government’s inadequate response to the famine constitute genocide?” is answered in the affirmative by the following undisputed facts:

- In 1846 Prime Minister Robert Peel succeeded in repealing the Corn Laws, eliminating protective tariffs on grain imports to the United Kingdom, thereby reducing the cost of grain and bread. The compelling reason for the repeal was the crop failure in Ireland. Peel also established the Relief Commission to coordinate relief measures in Ireland.

- Lord John Russell replaced Peel as prime minister in mid-1846. Russell immediately abolished Peel’s Relief Commission. Under Russell’s administration, all food depots except on the western seaboard were closed, public works were suspended, and local relief committees were forbidden to sell or distribute food at less than prevailing prices — which were inflated because of scarcity and speculation.

- The chief architect of these policies was Charles Trevelyan, assistant secretary of the treasury and director of government relief, who was knighted in 1848 “for his services to Ireland.” The motivation for these policies was attested to by none other than Trevelyan, who stated: “The great evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the {Irish} people.”

- In mid-1847, Parliament amended the Poor Law with the “Gregory Clause.” The effect of this clause was to forbid public relief to any household head who held more than a quarter-acre of land and refused to relinquish possession of the land to the landlord. The choice was either become landless or starve, and many Irish chose the latter. Those who chose eviction were at the tender mercies of the Russell administration, whose policies are described above.

- During the famine period, the wheat and other grain crops were unaffected and were reported to be “bountiful.” However, the Irish could not take advantage of those crops. The agricultural structure of the times required landlords to pay “rates” to Britain, which were due and payable even if the tenant farmer could not pay rent. Russell and Trevelyan never permitted an abatement on “rates,” with the result that wheat and other grains were exported to pay “rates” while millions of Irish starved. (The estimated deaths from the famine are between 1.1 and 1.5 million.)

Finally, Mr. Guinnane’s disingenuous observation that “by 1847 Ireland was a large net importer of food” misleads the reader. He fails to point out that throughout the famine period, Ireland exported 100,000 pounds sterling of food monthly, and almost throughout the period Ireland remained a net exporter of food.

Russell and Trevelyan’s laissez-faire economics cannot forgive or excuse the results of their policies in Ireland any more than Pol Pot’s political ideology can protect him from the ravages he visited on his people, which — as I recall — are being referred to as genocide. Similarly, the forced deportation of the Armenians by the Turks during World War I, resulting in untold deaths and suffering, is known as genocide — and I would not quarrel with that. —- DENNIS F. NEE Washington

Timothy Guinnane’s statements are surprisingly misleading. The disastrous potato famine of 150 years ago should and could have been avoided. During that famine, wealthy Irish Catholic landowners of the South continued to sell their abundant crops, their beef and their lamb to French, German and Low-Country markets rather than feed their own impoverished and starving tenant farmers. Aggravating the farmers’ reliance on the blighted potato was the number of young in each Catholic family. In the following four years, potatoes continued to be planted and new babies born, while in the Protestant North — with its same reliance on the staple potato — crisis was eased by the region’s industry and a landowner population caring for its poor.

Certainly the predominantly English Parliament also was at fault. Unfortunately, they were not made aware of the Irish famine until it had reached disastrous proportions and then behaved with far too typical indifference to a problem so non-English in much the same way they had behaved with our own American colonies some 70 years earlier. —- IRVING O’SHEA ROBINSON Baltimore

The Oxford English Dictionary defines genocide as the {attempted} deliberate and systematic extermination of an ethnic or national group. The Catholic Irish were an ethnic or national group.

During the famine, the British government deliberately and systematically adopted reckless and wanton policies of official neglect that exacerbated the famine’s savagery and substantially increased its cruel death count. Can inactivity be criminal to the point of homicide? I submit that it can and was in the circumstances of the Great Famine.

As force majeure masters of Ireland, the British had an affirmative duty grounded in justice to provide relief. They had the means and the ability to deliver such relief. They intentionally failed to do their duty because of their hostility to Irish Catholics — who then starved to death by the hundreds of thousands as their rich and well-fed British rulers complacently waited and watched. British inertia in such circumstances was callous, contemptible — and maliciously criminal to the point of second-degree murder. —- D. J. REARDON Leavenworth, Kan.

Reyna Grande didn’t know about the Saint Patrick’s Battalion until someone at a book reading suggested that she write about the group of European, primarily Irish, soldiers who fought for the Mexican Army in the Mexican-American War.

+—+

Read this great document, The Great Irish Famine

The Song of the Famine

By Anomymous

Want! want! want! Under the harvest moon;

Want! want! want! Thro’ dark December’s gloom;

To face the fasting day upon the frozen flags!

And fasting turn away to cower beneath a rag.

Food! food! food! Beware before you spurn,

Ere the cravings of the famishing to loathing madness turn;

For hunger is a fearful spell, And fearful work is done,

Where the key to many a reeking crime is the curse of living on !

For horrid instincts cleave unto the starving life,

And the crumbs they grudge from plenty’s feast but lengthen out the

strife –

But lengthen out the pest upon the fetid air,

Alike within the country hut and the city’s crowded lair.

Home! home! home! A dreary, fireless hole –

A miry floor and a dripping roof, and a little straw — its whole.

Only the ashes that smoulder not, their blaze was long ago,

And the empty space for kettle and pot where once they stood in a row!

Only the naked coffin of deal, and the little body within,

I cannot shut it out from my sight, so hunger-bitten and thin; –

I hear the small weak moan – the stare of the hungry eye,

Though my heart was full of a strange, strange joy the moment I saw it

die.

I had food for it e’er yesterday, but the hard crust came too late –

It lay dry between the dying lips, and I loathed it — yet I ate.

Three children lie by a cold stark corpse In a room that’ s over head –

They have not strength to earn a meal,

Or sense to bury the dead!

And oh! but hunger’s a cruel heart, I shudder at my own,

As I wake my child at a tearless wake, All lightless and alone!

I think of the grave that waits, and waits but the dawn of day,

And a wish is rife in my weary heart –I strive and strive, but it won’t

departI cannot put it away.

Food! food! food! For the hopeless day’s begun;

Thank God there’s one the less to feed! I thank God it is my son!

And oh! the dirty winding sheet, and oh! the shallow grave!

Yet your mother envies you the same of all the alms they gave!

Death! death! death! In lane, and alley, and street,

Each hand is skinny that holds the bier, and totters each bearer’s feet;

The livid faces mock their woe, and the eyes refuse a tear;

For Famine’s gnawing every heart, and tramples on love and fear!

114.

Cold! cold! cold! In the snow, and frost, and sleet,

Cowering over a fireless hearth, or perishing in the street,

Under the country’s hedge, On the cabin’s miry floor,

In hunger, sickness, and nakedness, it’s oh! God help the poor.

It’s oh! if the wealthy knew a tithe of the bitter dole

That coils and coils round the bursting heart like a fiend, to tempt the

soul!

Hunger, and thirst, and nakedness, sorrow, and sickness, and cold,

It’s hard to bear when the blood is young, and hard when the blood is

old.

Sick! sick! sick! With an aching, swimming brain,

And the fierceness of the fever-thirst, and the maddening famine pain.

On many a happy face to gaze as it passes by –

To turn from hard and pitiless hearts, and look up for leave to die.

Food! food! food! Through splendid street and square,

Food! food! food! Where is enough and to spare;

And ever so meager the dole that falls, What trembling fingers start,

The strongest snatch it from the weak, For hunger through walls of stone

would break

It’s a devil in the heart!

Like an evil spirit, it haunts my dreams, through silent, fearful night,

Till I start awake from the hideous scenes, I cannot shut from my sight;

They glare on my burning lids, and thought, like a sleepless goul,

Rides wild upon my famine-fevered brain — Food! ere at last it come in

vain

For the body and the soul!

The Famine, or An Górta Mór, the Great Hunger, took more than one million lives, between those that died of starvation and those that left Ireland for a better life in America or elsewhere in the world. Those who were left behind in Ireland experienced a desperation that led to a massive change in politics and nationalism – it was only a few years later, in 1858 that the Irish Republican Brotherhood was founded. The British government and the British and Irish Protestant landowners still required the Irish peasants and laborers to pay their rent for the land they could not work due to the blight and the hunger upon them. In a lush island surrounded by water teaming with fish and land that fattened pig and cattle alike, how could one failed crop cause a Famine? According to British law, Irish Catholics could not apply for fishing or hunting licenses. Their pigs and cattle were sent to England to feed the British and to export for trade, while the landlords kept the fine cuts for themselves. Ireland was part of the British Empire, the most powerful empire in the world at that time – yet the British government stood by and did nothing to help their subjects overcome this hardship. In our time, an enforced famine such as this would be labeled genocide yet in the 1800s it was merely an unfortunate tragedy.

As defined in the United Nation’s 1948 Genocide Convention and the 1987 Genocide Convention Implementation Act, the legal definition of genocide is any of the acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, including by killing its members; causing them serious bodily or mental harm; deliberately inflicting on a group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; and forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. The British policy of mass starvation inflicted on Ireland from 1845 to 1850 constituted “genocide” against the Irish People as legally defined by the United Nations.

A quote by John Mitchell (who published The United Irishman) states that

“The Almighty indeed sent the potato blight, but the English created the Famine”.

A caption under a picture shown in The Pictorial Times, October 10, 1846, best describes the circumstances of the great starvation, and the nature of the genocide:

“Around them is plenty; rickyards, in full contempt, stand under their snug thatch, calculating the chances of advancing prices; or, the thrashed grain safely stored awaits only the opportunity of conveyance to be taken far away to feed strangers…But a strong arm interposes to hold the maddened infuriates away. Property laws supersede those of Nature. Grain is of more value than blood. And if they attempt to take of the fatness of the land that belongs to their lords, death by musketry, is a cheap government measure to provide for the wants of a starving and incensed people.”(Food Riots, 2)