Charlie Chaplain, Gypsy!

Note: Cut and Pasted. Enjoy!

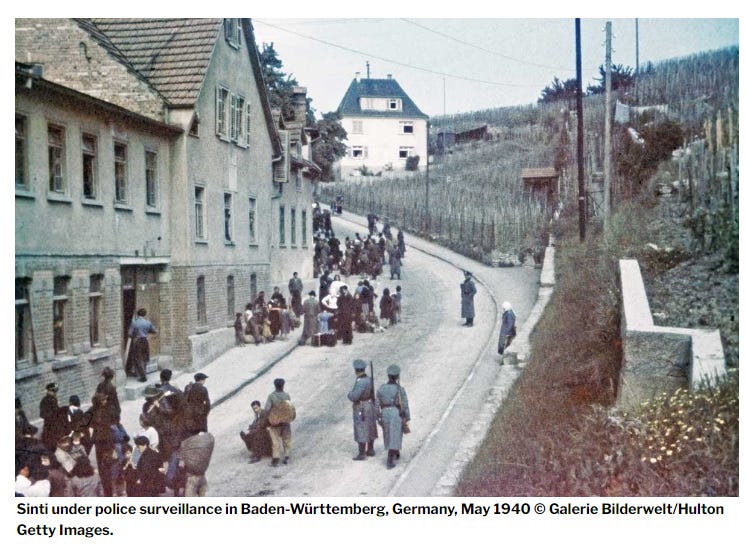

In the first article in this series [ Fascination and Hatred: The Roma in European Culture ] I approached the issue of anti-Roma racism and the Third Reich via a long prehistory of Roma in Europe until 1900. This was a story of misperception, misrepresentation, and stereotypes. These misrepresentations and stereotypes, I tried to show, possessed a peculiar double character. The Romani culture and lifestyle were both repellent to many Europeans as something alien and corrupt and yet quite fascinating for their seeming non-integration to the world of wage-labor, time-discipline, and the proverbial “rat-race.” During the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the emergence of race theory posed a fundamental challenge, however, to European Roma (in addition to many other groups). Governments in Central Europe attempted to define “Gypsies” as a “race,” as a group defined by shared biological characteristics.

“the Bavarian precedent”

During the 1880s and 1890s, Imperial Germany, newly unified under the conservative Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, saw the growth of enormous resentment against Roma. Those Romani men and women who had lived in Germany for generations, known as Sinti, had experienced more than their fair share of hostility. Yet they were not the principal targets.

In what will sound like a very familiar story to an early twenty-first century audience, it was immigration that generated this backlash. Many Romani families left Hungary and Romania and relocated to Germany because of the country’s prosperity. Speaking a variant of the Romani language indebted to Romanian and often more darker-skinned, these newcomers suffered a ferocious response from authorities.

Among the German states, the Kingdom of Bavaria proved the most zealous in its anti-Roma measures. In 1885, the Bavarian government passed a law tightening the distribution of licenses to Romani traders. This legislation targeted the itinerant, i.e. those who moved from community to community, and made it easier to revoke licenses already granted. Moreover, the 1885 law swept up undocumented Roma. Once non-citizens were incarcerated, they were forced to pay for all legal costs up to and including expulsion from the Kingdom.

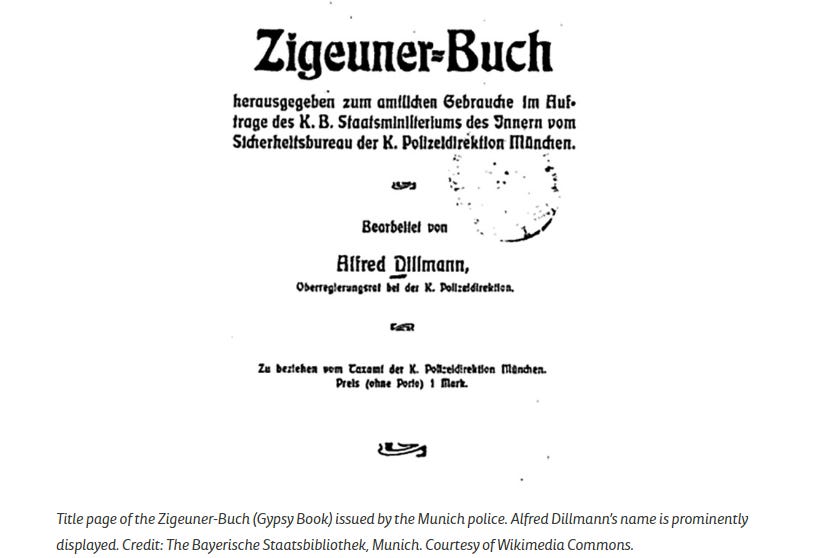

Although Roma adjusted to the new, harsh reality and more and more of them began to shift away from the traditional ways of travel and settled into communities in southern Germany, social and political anxiety about their presence did not abate. A truly frightening step was taken in Bavaria in 1899, when security police in Munich created a “Central Office for Gypsy Affairs.” The director, Alfred Dillmann, established a disquieting precedent for surveillance and information-gathering. According to Guenter Lewy, he instructed local police to compile reports on Roma, detailing “the nature of the identity papers they carried, how many animals, especially horses, the itinerants had, from where they had come and in which direction they had moved, and whether the police had taken any measures against them.”

Sound fucking familiar? Oh, Jerusalem! Central Office for Gypsy Affairs — 130 laws passed against Romani.

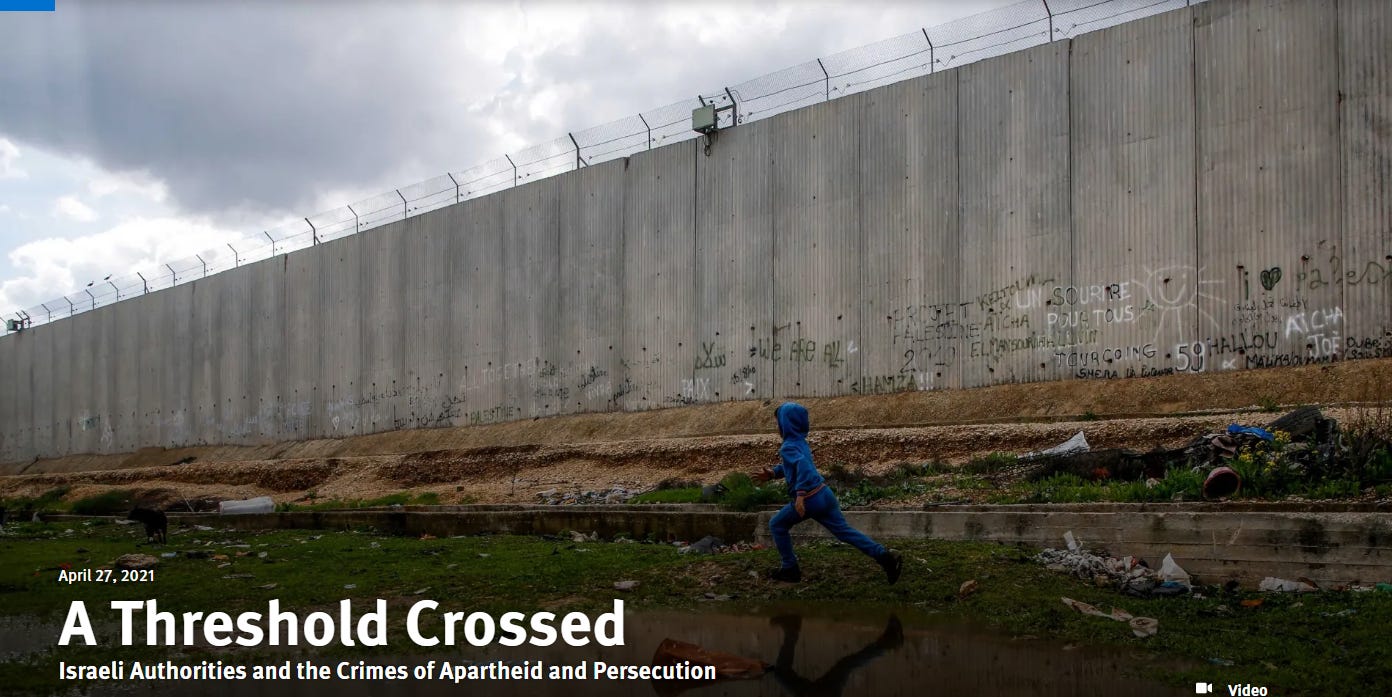

While Israel passed a “nation-state” law that further marginalises Palestinian citizens, such legislation is nothing new.

There are currently more than 65 Israeli laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens in Israel and Palestinian residents of the Occupied Palestinian Territories, according to Adalah, The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel.

Adalah’s database shows how Israel’s laws – dating as far back as 1939 – discriminate against Palestinians.

Before Fucking Oct. 7: Laws against being a human, a la Jewish State of Israel.

Right to acquire, lease land

Right to return

According to the Absentees’ Property Law (1950), Palestinian refugees expelled after November 29, 1947, are “absentees” and are denied any rights. Their land, houses/apartments, and bank accounts (movable and immovable property) were confiscated by the state.

Simultaneously, the Law of Return (1950) gave Jews from anywhere in the world the right to automatically become Israeli citizens.

Right to residency

Right to family life

The Ban on Family Unification – introduced as an emergency regulation in 2003 following the outbreak of the second Intifada in 2000 – prevents family unification when one spouse is an Israeli citizen and the other is a resident of the occupied territories.

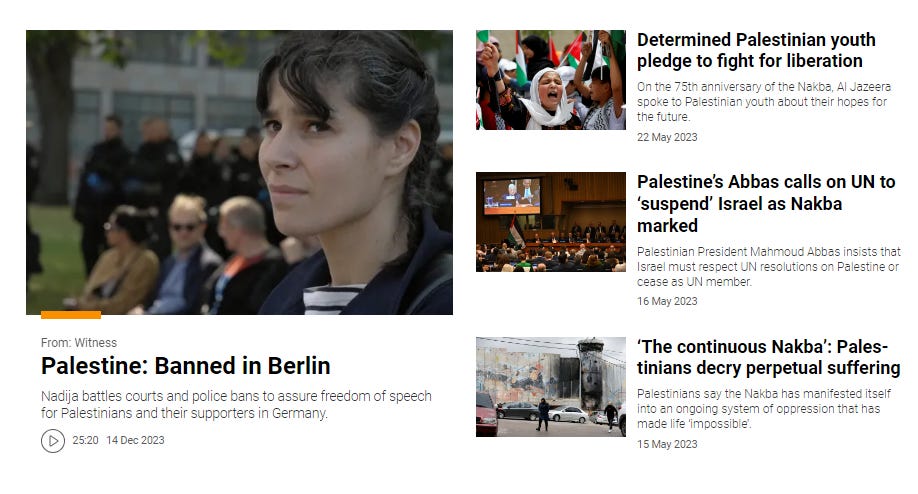

Right to commemorate Nakba

Palestinians traditionally mark Israel’s official Independence Day as Nakba Day, a day of mourning and commemoration marking the expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians in 1948 to make way for the creation of the state of Israel.

The Nakba Law introduced in 2011 allows the finance minister to reduce funding or support to an institution if it holds an activity that commemorates Israel’s Independence Day as a day of mourning.

“The law causes major harm to the principle of equality and the rights of Arab citizens to preserve their history and culture. The law deprives Arab citizens of their right to commemorate the Nabka, an integral part of their history,” Adalah wrote.

+—+

Attraction to Roma mixed with the older suspicion and hostility in explosive ways. It is particularly visible in Georges Bizet’s famous opera, Carmen. First performed in Paris in 1875, it tells the story of a Spanish soldier Don José, who falls in love with the fiery Carmen, a dazzling Romani dancer. Ultimately, he abandons his childhood sweetheart for her. Yet Carmen gives her love to another, Escamillo. In a rage, Don José kills her. This fusion of allure and deceit in Carmen has packed audiences into concert halls and movie theaters (there have been several movie versions of it) for generations.

Parts of the opera, argued Marxist social thinker Theodor W. Adorno, express an

“envy of the colorful and unfettered lives of those who are outlawed from the bourgeois world of work, condemned to hunger and rags and suspected of possessing all the happiness which the bourgeois world denies itself in its irrational rationality.”

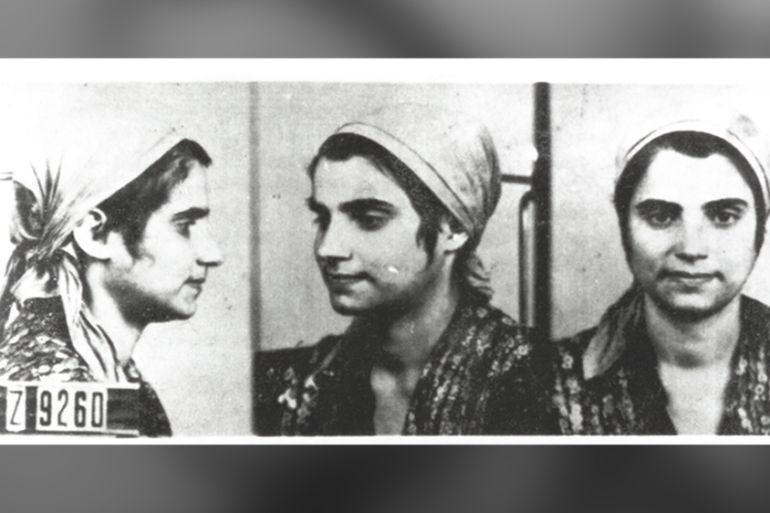

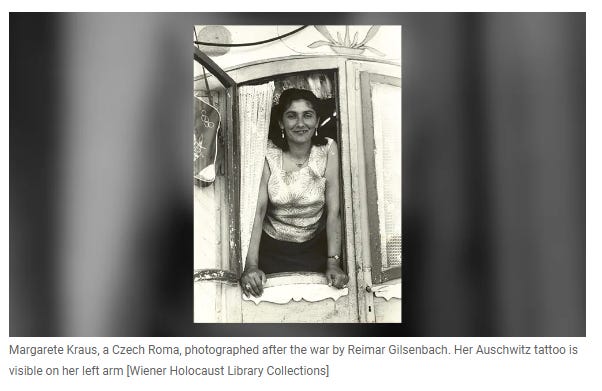

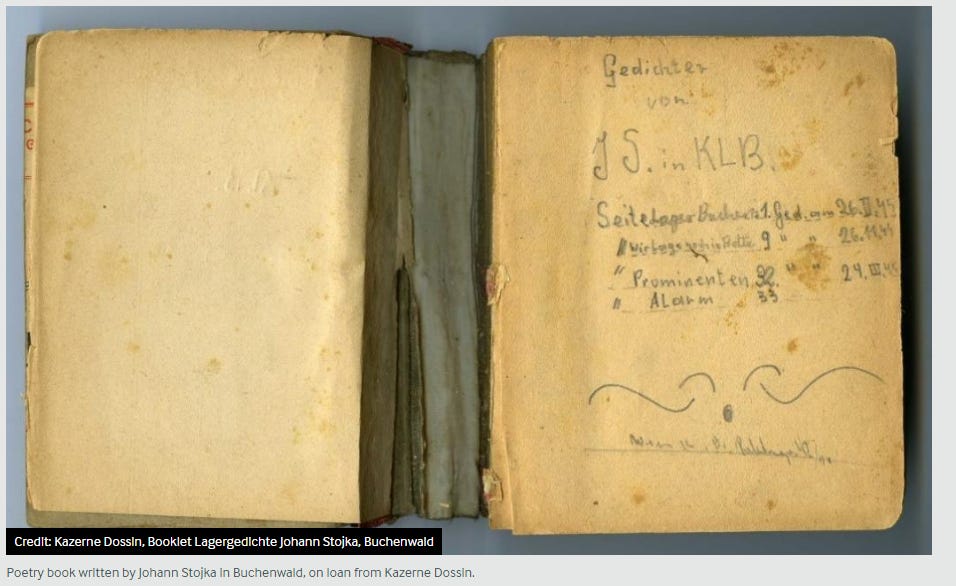

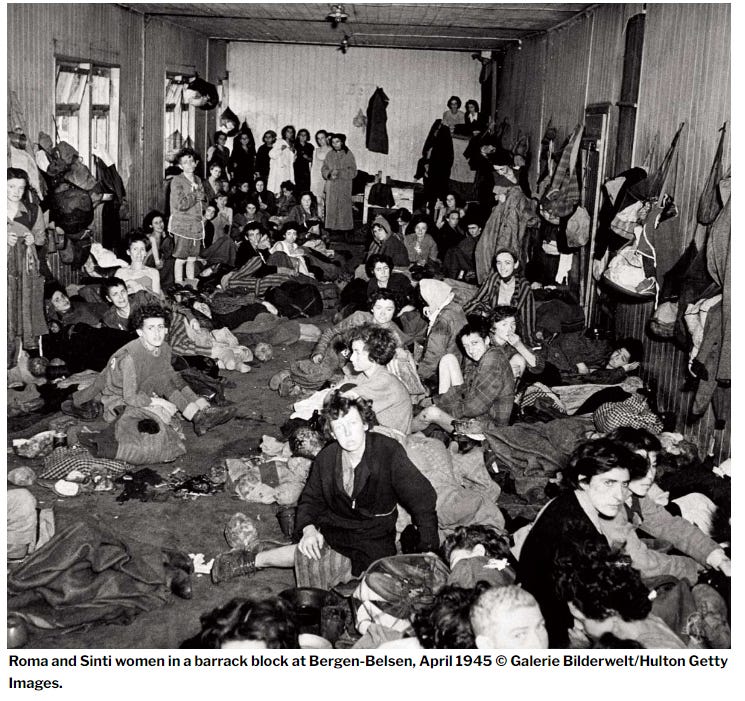

She survived the Holocaust. Her parents did not.

They were among the 250,000 to 500,000 Roma and Sinti people – between 25 and 50 percent of the minority’s entire population in Europe at the time – murdered by Nazis and their collaborators during the second world war.

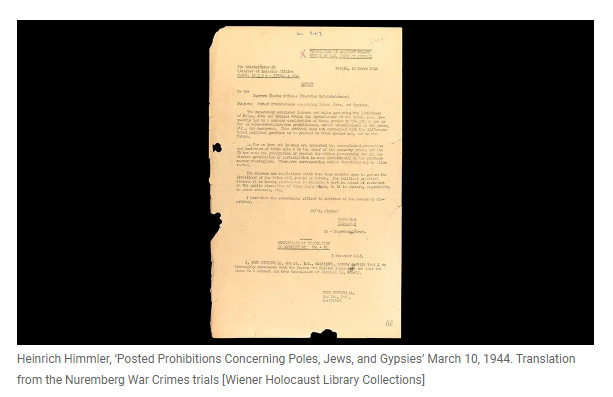

Kraus’s story features in a new exhibition at London’s Wiener Holocaust Library.

The exhibition, Forgotten Victims: The Genocide of the Roma and Sinti, seeks to uncover this often-ignored aspect of the second world war. It examines the persecution of Roma people in Europe in the years leading up to the war, genocidal policies towards them during Nazi rule, and the community’s ongoing struggle for recognition and restitution.

“Even if people are aware that the Nazis targeted Roma as well as Jews, it isn’t necessarily a subject that people know that much about,” said Barbara Warnock, the curator of the exhibition.

“The genocide that occurred against Roma across Europe was a comparable policy to that against the Jewish community, but it was more piecemeal, less systematically pursued.”

It is frequently said in discussions about the enormity of the Third Reich’s crimes that there is insufficient attention to the mass murder of Roma. This is indisputably true. Yet it is misleading to merely add several hundred thousand Romani victims to the six million Jews annihilated by the Nazi terror apparatus. The deaths of these men, women, and children, murdered as “Gypsies,” cannot be reckoned in terms of an “also,” an “in addition to,” or “it cannot be overlooked that. . . .” One must not consider their destruction as an addendum to the Judeocide at all. While the Hitler regime’s targeting of Roma in several European countries during World War II coincided and intersected with the Holocaust, the former derived from a form of racism distinct from genocidal anti-Semitism. To understand anti-Roma racial hatred, one must examine the longer history of Roma in European culture.

This dynamic of fascination and hatred, still relatively new in European history, entered a new phase in the last third of the nineteenth century with the emergence of race theory. The attempt by race thinkers like Arthur de Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain to divide humans into distinct races within frameworks of superiority and inferiority, the effort to explain culture and behavior by recourse to biology, and the fear of “race-mixing” would have terrible consequences for Romani communities. In the next article in this series, I will look at just how these consequences unfolded.

Another reason is less obvious.

“There have been many books, not exclusively but mostly by Jewish authors, about the Holocaust and the fate of the Jews,” Hancock said.

“In the Romani case, there was limited literacy. We have a nomadic tradition and an oral history tradition. We just were not equipped – and to a large extent are still not equipped – to do the scholarship or to write books.” (source —Roma Holocaust: Amid rising hate, ‘forgotten’ victims remembered )

Another Roma boy dies in police chase, marking grim pattern in Greece

‘My father didn’t beat my mother in a gypsy fashion-he just beat her’

Roma pushed to turn on Ukrainian refugees in Czech Republic

Why Europe needs Roma to drive its economy

In the comedy special ‘His Dark Material’, Jimmy Carr joked about the Roma Holocaust:

‘When people talk about the Holocaust, they talk about the tragedy and horror of 6 million Jewish lives being lost to the Nazi war machine. But they never mention the thousands of Gypsies that were killed by the Nazis. No one ever wants to talk about that, because no one ever wants to talk about the positives.’

Carr’s joke has sparked widespread outrage – yet some voices have defended it as ‘gallows humour’. Back in 2017, the author Alexandra Erin, in a Twitter thread on comedy, wrote ‘If the person on the gallows makes a grim joke, that’s gallows humor. If someone in the crowd makes a joke, that’s part of the execution.’ And here, Carr wasn’t speaking from the gallows; those on the gallows are in fact, one of the most oppressed and discriminated against groups to this day: the Roma, and within the scope of the joke, the European Roma and Sinti targeted in the Holocaust.

Known as the Porajmos, meaning ‘the Devouring’ in the Romani language, estimates on numbers of victims are as high as 1.5 million, rather than the downplaying ‘thousands’ (Hancock, 2004, p.392). In 1997, Roman Herzog, the Federal President of Germany at the time, affirmed:

‘The genocide of the Sinti and Roma was carried out from the same motive of racial mania, with the same premeditation, with the same wish for the systematic and total extermination as the genocide of the Jews. Complete families from the very young to the very old were systematically murdered within the entire sphere of influence of the National Socialists’

The Roma are an ethnic group originating in Northern India, in the Punjab and Rajasthan regions. Although traditionally nomadic, the vast majority of Roma are now settled, and many in the UK are recent immigrants from Europe, particularly Eastern Europe. They are a different group from the UK Traveller community, who also face cruel persecution, and with whom the Roma share a history of nomadism. As a now settled ethnic group of Indian origin, many speaking an Indo-Aryan language, known as Romani and related to Hindi and Punjabi, the Roma face a very particular set of challenges in both continental Europe and the UK. And their history of persecution is not a recent one: in Romania, they faced 500 years of slavery. In Wallachia (territory of modern-day Romania), through to the mid-nineteenth century, all Roma were born slaves, were property, and could be bought and sold at will (see Hancock, 2005, p.21). An account from a Romanian periodical magazine, ‘Cugetul Românesc’, describes how they were priced per ‘okka’ (a measure for weight equalling roughly 1.2 kilograms) of meat.

Across Europe, they are known by some variation of the term ‘tsigan’, derived from the Byzantine Greek ἀθίγγανοι, athinganoi, meaning ‘untouchables’. The term was associated with a Monarchian sect, and historians suggest that it became associated with the Roma due to their perception as outsiders (see Wesler, 1997, p. 126). As Hancock notes in the entry on the Roma Holocaust in the Encyclopedia of Genocide, ‘[a]s a non-Christian, non-white people, Asian people possessing no territory in Europe, Roma were outsiders in everybody’s country’ (Hancock, 1999, p.501).

That fucking EuroTrashLandia:

‘have to get sunburned, make a mess with your family, put up fires on town squares, and only then some politicians would say, “He is a really miserable man.”’

An aggregation of data from 1892 to 2009 across 14 published dictionaries of the Romanian language has shown the correlation between definitions attached to the Roma, skin colour, and demonisation. The term ‘țigănos’ (adjectival form of ‘țigan’) was defined as ‘negricios’ – a term whose root is obvious, and which translates as ‘blackish’, ‘swarthy’; this was immediately followed by ‘having bad manners’. In 2007, Jiří Čunek, the Czech Deputy Prime Minister said that in order to receive state benefits, one would ‘have to get sunburned, make a mess with your family, put up fires on town squares, and only then some politicians would say, “He is a really miserable man.”’ The sunburn reference alludes once again to the brown, racialised Roma, and inherently links the Roma with antisocial behaviour.

In 2013, Gilles Bourdouleix, member of National Assembly, France, stated: ‘Maybe Hitler didn’t kill enough of them’. Earlier the same year, Zsolt Bayer, co-founder of Hungary’s Fidesz Party, stated:

‘A significant part of the Roma are unfit for coexistence. They are not fit to live among people. These Roma are animals, and they behave like animals. When they meet with resistance, they commit murder. They are incapable of human communication. Inarticulate sounds pour out of their bestial skulls. At the same time, these Gypsies understand how to exploit the ‘achievements’ of the idiotic Western world. But one must retaliate rather than tolerate. These animals shouldn’t be allowed to exist. In no way. That needs to be solved — immediately and regardless of the method.’

References

Grellmann, H. (1787). Dissertations on the Gipsies, trans. Matthew Raper. London: Printed for the editor, by G. Bigg, and to be had of P. Elmsley, and T. Cadell … and J. Sewell.

Hancock, I. (1999) ‘Roma: Genocide of Roma in the Holocaust. Encyclopedia of Genocide, Vol. I, A-H, ed. Israel W. Charny (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide.

Hancock, I. (2004). ‘Romanies and the Holocaust: A Reevaluation and an Overview’. The Historiography of the Holocaust, ed. Dan Stone. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hancock, I. (2013). We are the Romani people. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press.

Kenrick, D., and Puxton, G., The Destinies of Europe’s Gipsies (1972). Colombus Centre: Everyman Paperback.

Matache, M. and Bhabha, J. (2021) ‘The Case for Roma Reparations’. Time for Reparations: A Global Perspective. Edited by Jacqueline Bhabha, M. Matache, and C. Elkins. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Wesler, P. (1997) The Case for the Relexification Hypothesis in Romani. Relexification in Creole and Non-Creole Languages, eds. Julai Horvath, P. Wesler. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

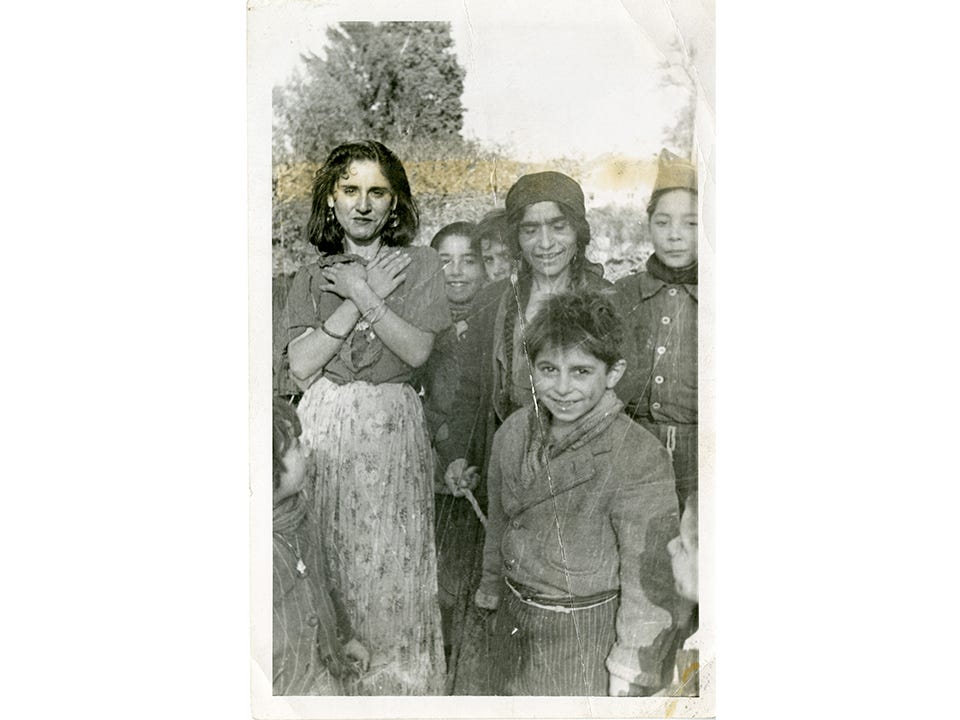

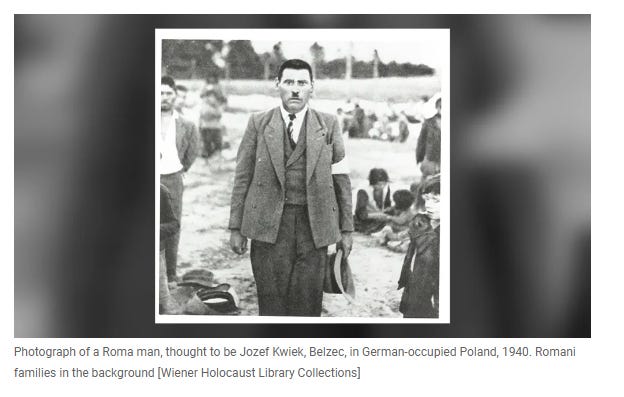

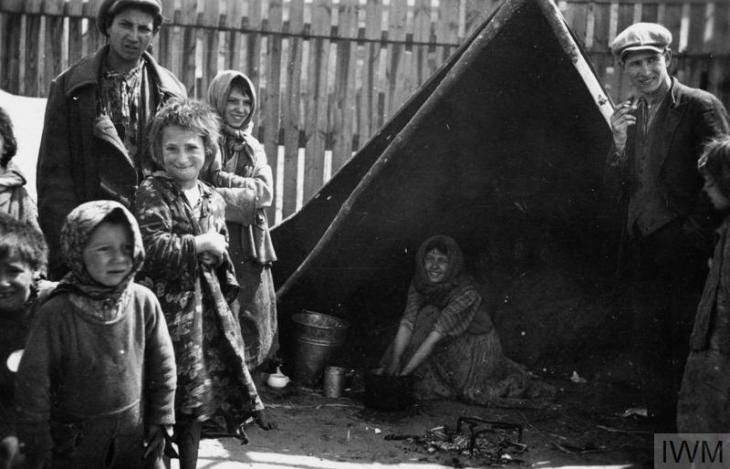

Who counted as a ‘Gypsy’? There was – and still is – a huge difference between the way outsiders classified ‘Gypsies’ and how the diverse Roma and Sinti communities across Europe defined themselves. Contrary to popular belief, Romani communities were not isolated from the societies in which they lived, but were intimately connected through economic, social and cultural ties, evident in the integrated communities of rural Moravia, the Roma hamlets on the outskirts of villages in the Austrian Burgenland and Transylvania, or the peripatetic Sinti or Manouche families of Germany or France.

From the late 18th century, however, European states increasingly defined Gypsies as inherently criminal and dangerous, a problem to be solved, either by assimilation or expulsion. The ‘enlightened’ Austrian emperor Joseph II wanted Gypsies to become Austrian citizens and required them to settle, give up their language and in some cases also their children, whereas the German states relied on expelling itinerant Roma across municipal borders. In the 19th century, police forces and local authorities sought ‘objective’ definitions of Gypsies from the emerging sciences of criminology and physical anthropology. The Austrian criminologist Hans Gross’ Handbuch für Untersuchungsrichter (‘Handbook for Investigative Judges’), first published in 1893 and followed by six editions and numerous translations, devoted an entire chapter to claims about the alleged physical and psychological characteristics of ‘the Gypsy’, who was defined as ‘different from every man of culture, even from the crudest and most degenerate’.

You feeling the genocide love of Palestinians yet? Jews in Israel? All those laws?

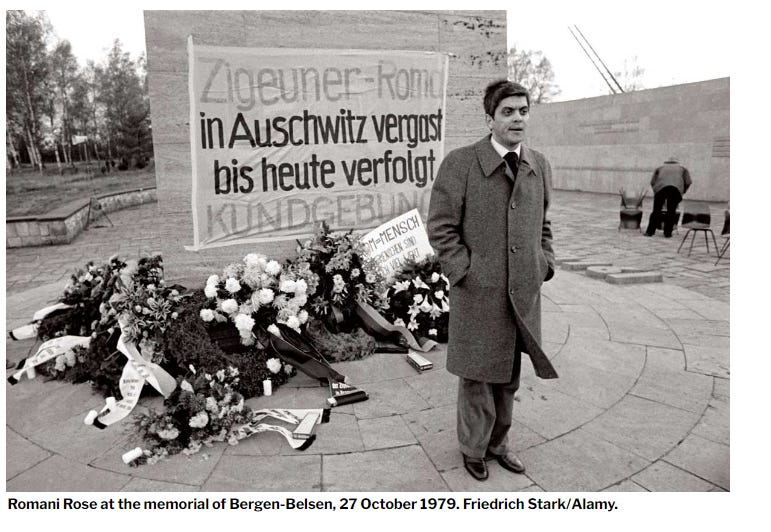

Official reluctance to recognise Roma as victims of persecution on racial grounds blocked compensation claims for Romani survivors in both western and eastern Europe. In West Germany, Sinti and Roma waged legal battles for two decades to rectify the opinion of the Federal Supreme Court that Roma had not faced racial discrimination until Himmler’s Auschwitz decree of 1942. It took 30 years for West Germany to recognise that the Hereditary Health Law, under which approximately ten per cent of German Roma were sterilised, was a racially motivated pillar of the Final Solution. In the 1970s, the German civil rights activist Romani Rose, born in Heidelberg in 1946, and his uncle Oskar, who had survived Auschwitz, set up the Association of German Roma. Rose organised a hunger strike in the former concentration camp at Dachau in 1980 to attract international attention to the genocide and to protest against continued use of prewar and wartime files on Gypsies by the German police, decades after the end of the war.

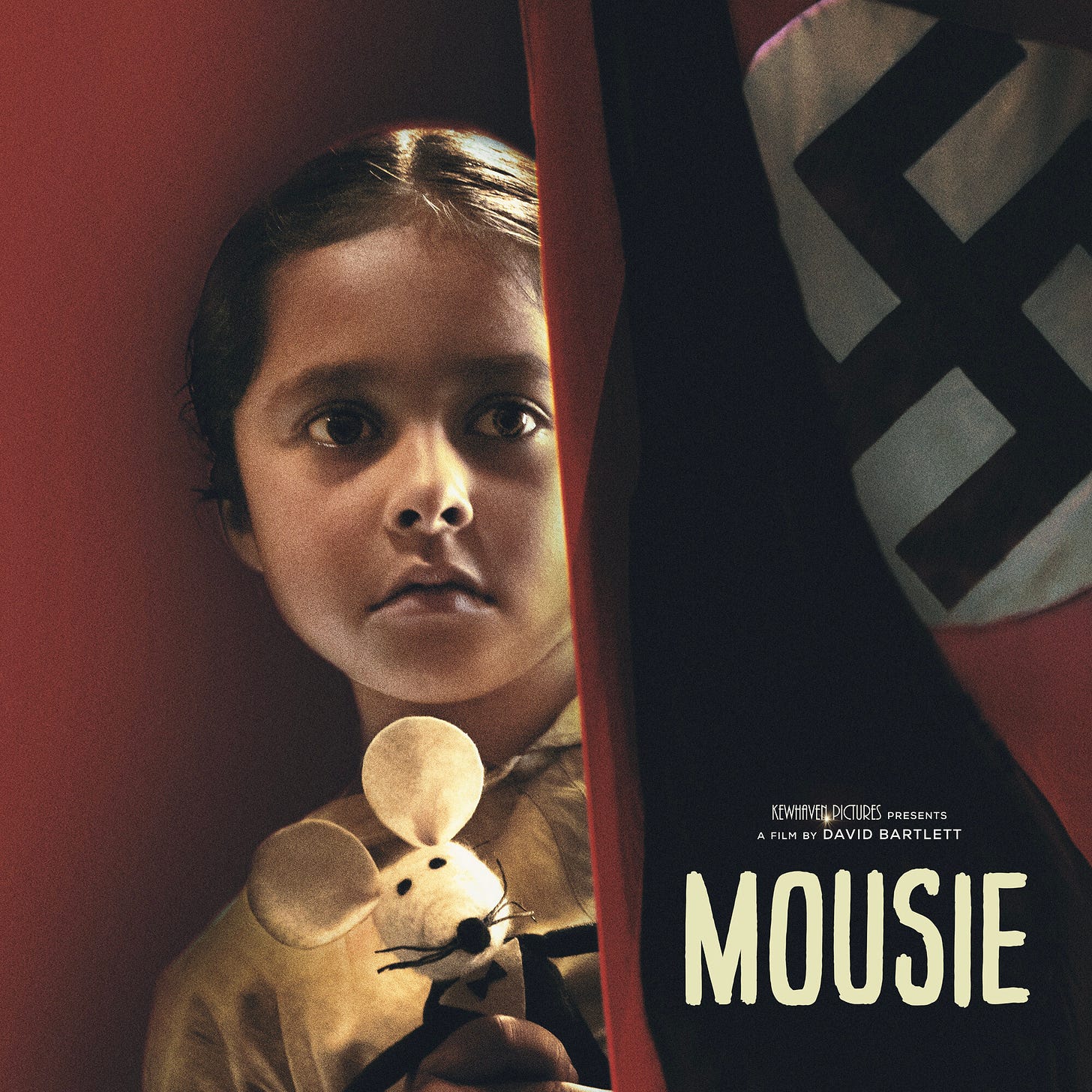

Berlin 1936. Hitler will soon host the Olympics, and the streets are being “cleansed” of Jews and Roma “Gypsies”. Inside a dying Weimar Kabarett club, seven-year-old Roma Helene (Sasha Watson-Lobo) hides in a wardrobe, concealed by tap-dancer Katharina (CJ Johnson) who plans to escape the poison of Nazism and take Helene to America – where everyone is welcome, no matter the colour of their skin.

But Helene won’t rest. Sneaking about unseen, the little mouse sees everything – a dancing devil, a nervous stage-manager, an alcoholic “new age Nazi” comedian. And the arrival of awkward Nazi conscript, Otto (Jack Bennett). Finding his feet as a newly-empowered thug, he clumsily makes a pass at Katharina, but greater jeopardy awaits as he discovers the little mouse. Only the child’s ingenuity and talent will save her now…

The biography of Bronisława Wajs, commonly known as Papusza, is the first Polish film set mostly in Romani language. Papusza was one of the few literate people among Polish-Romani women before World War II and became a famous poet, who was discovered by Jerzy Ficowski, a writer and translator, in 1949.

Although her poetry was widely admired and translated into many languages, she was bullied by the Roma community for forsaking the traditional role of woman and for allegedly revealing the details of Romani culture. Banned from her environment, she fell into mental illness and was forced to spend some time in a mental hospital.

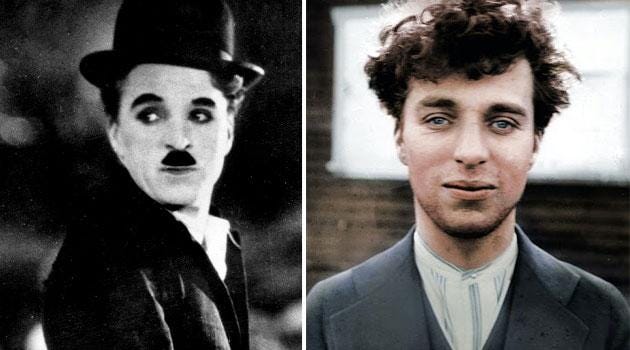

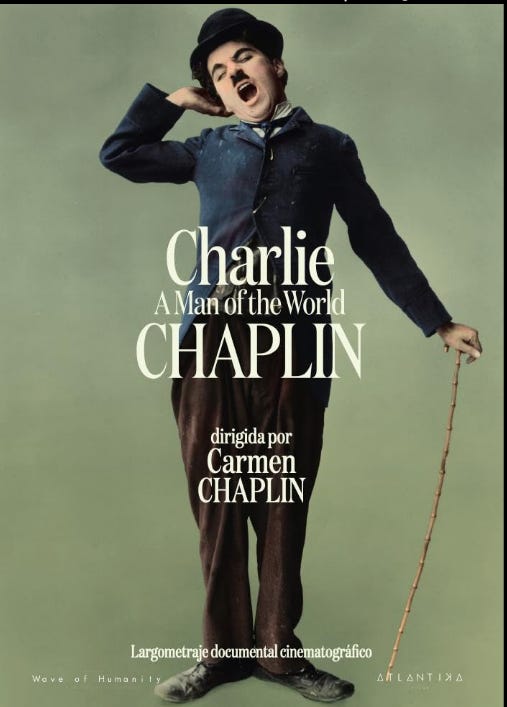

In their documentary film called “Charlie Chaplin. A Man of the World“, the sisters Carmen and Dolores Chaplin are investigating their grandfather’s Romani origin. Some of the first clips from the film were presented by them at the BCN Film Fest underway in Barcelona last week.

This is the first time the Chaplin family has contributed to such a degree on a film about Charlin Chaplin, both as authors and producers. They say the documentary “radically reinterprets Chaplin’s work from a Romani perspective and, through that lens, investigates the persecution of the Roma.”

The documentary focuses on the Romani roots of film legend Charlie Chaplin, the circumstances of his birth and his childhood period, and how his Romipen affected his art. The film also offers a new, unique view of Chaplin’s life and films, as well as celebrating Romani culture.

In his autobiography, Chaplin himself made no secret of the fact that both his father and mother were themselves half-Romani. He never had a birth certificate but was said to have been born on 16 April 1889 in London, England.

After his death in 1977, a letter was found in his nightstand addressed to him by a Romani correspondent. It describes the night on which Chaplin is said to have been born at a Romani camp in a caravan in Black Patch Park, Smethwick in central-western England.

That letter was discovered by Chaplin’s daughter Victoria, and her brother Michael has reflected on it as follows: “My father received thousands of letters from all over the world. Why would he have kept that one if it didn’t mean something to him?”

“He was very well aware of his Romani roots and told my father and his other children about them. It was something he was proud of, but it was overlooked,” granddaughter Carmen Chaplin told Variety magazine at the San Sebastian film festival in 2019, where the sisters announced they were making their documentary.

Both sisters admit the idea to make the documentary came out of their “grandfather’s passion to find his Romani roots”, which he handed down to their own father, Michael Chaplin. While Michael “left home at the age of 16, he maintained deep feelings for his father all his life”.

“Grandfather was born in the straight-laced Victorian era, while my father was brought up in the atmopshere of the 1960s. Despite the differences in their educations, however, they shared an interest in tracking down their Romani origins. It was infectious,” recalls Dolores Chaplin, explaining that “the documentary investigates the Romani roots of the Chaplins

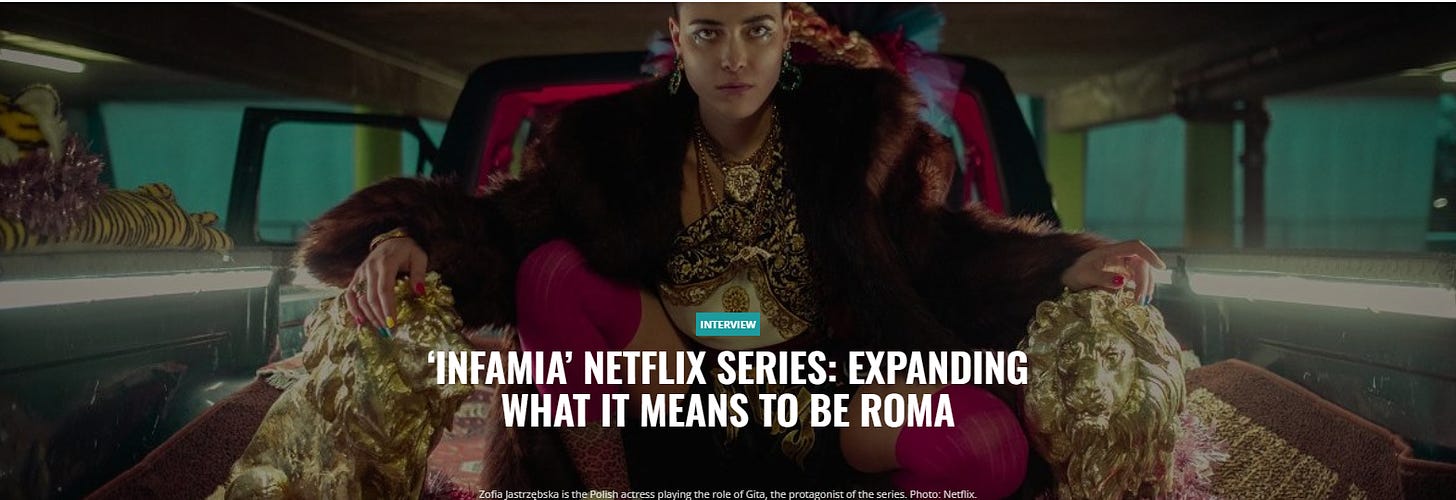

Joanna Talewicz, who acted as an advisor on Roma culture for the series, tells BIRN in an interview in Warsaw that Gita ultimately arrives at her own version of being Roma, “which is the result of balancing different realities” – her Roma roots, the multicultural exposure she got in the West and continues to get via the internet and culture, and her relations to the non-Roma majority in her village.

Though the show was the initiative of non-Roma director Anna Maliszewska, Talewicz points out that around 300 Roma were involved in its production, including non-professional actors playing key protagonists such as Gita’s grandmother. Many of the scenes were filmed in a real Roma settlement at Maszkowice in southwest Poland.

Talewicz also highlights that the show’s creators were inspired by emancipatory projects emerging in the Roma communities themselves over the last few years.

“It is not accidental that Gita expresses herself through hip-hop,” Talewicz says. “Hip-hop always came from revolt, from poverty. It was created by the grassroots and it gave a louder voice to those who felt excluded and marginalised, it allowed them to express their disappointment and anger.” (source)

Her own favourite scene from the series is when, after Gita posts a controversial music video online, her grandmother refuses to let her inside the house saying, “You are not ours any more”. In turn, Gita calmly yet forcefully says, “Yes, I am.”

“This is my story and the story of so many people,” Talewicz says. “I’ve been told I am not a real Roma for making this series. But who is to say what is a real Roma? Even if it is hard, we need to be ourselves – this is how we set new boundaries and how we move forward.”

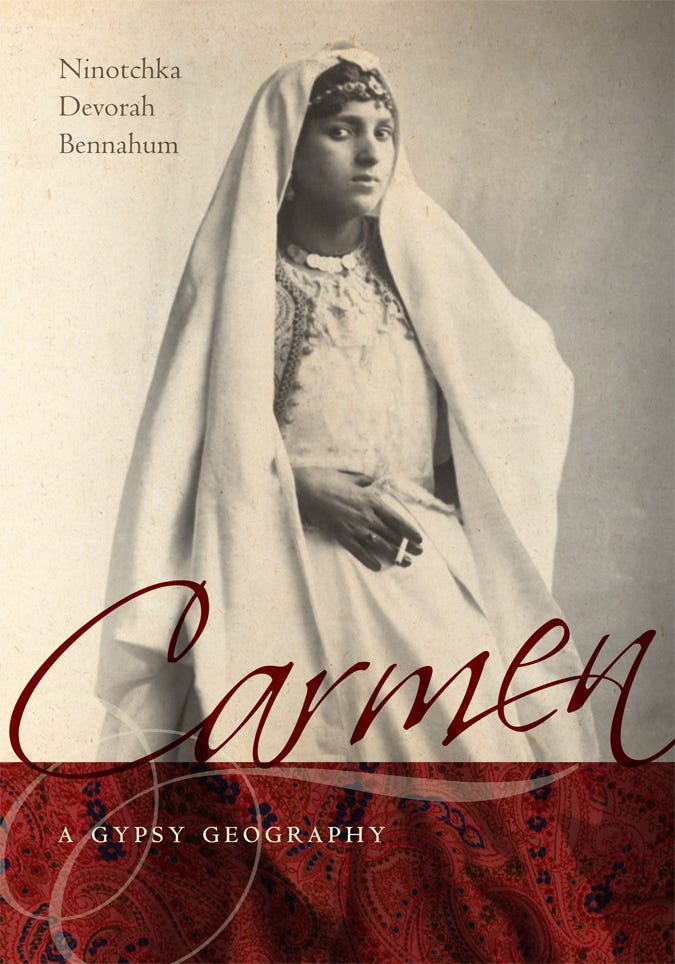

In her new book, “Carmen –– A Gypsy Geography” (Wesleyan University Press, 2013), Ninotchka Bennahum, a professor of dance and theater at UC Santa Barbara, presents Carmen as “an embodied historical archive, a figure through which we can consider nomadic, transnational identity and the immanence of performance as an expanded historical methodology.”

Bennahum traces the genealogy of the female Gypsy presence in her iconic operatic role from her genesis in the ancient Mediterranean world, her emergence as flamenco artist in the architectural spaces of Islamic Spain, her persistent manifestation in Picasso’s work and her contemporary relevance on stage.

“The book began as a history of Carmen and an archival and performative evolution of Spanish and Gypsy dance on the French Romantic stage,” said Bennahum, a dance historian and performance theorist. “But as I searched, I became intrigued by the idea of migration. It’s choreographic. I found I was really interested in migration, nomadology, homelessness and art as the receptacle of cultures that travel. Gypsy people –– flamenco artists –– carry their histories with them on their backs. So I looked at Carmen as a mythic figure, a woman from polytheistic lands in the Ancient Middle East.”

According to Bennahum, Carmen’s history is mytho-poetic and feminist. “On another level it’s also a dance history, and on still another it’s an operatic history. But it really belongs to Carmen, who emerges out of the sand like an avatar and affects people by dancing. And inside the dance is an archeology of time and dancing and history. If you know how to read the dance, you can read the history,” she said.

SPOKANE — Gypsy leader Jimmy Marks, a flamboyant gadfly who battled City Hall for decades and placed a curse on Spokane, died Wednesday at Sacred Heart Medical Center.

Mr. Marks, 62, had been in critical condition since Friday, when he suffered a heart attack at his dentist’s office. The death of the nationally known Gypsy civil-rights leader was confirmed by the hospital and by attorney Russell Jones, a family friend.

Mr. Marks became famous in 1986 when police raided his home and that of his father, Grover, looking for stolen items. They found $1.6 million and $160,000 in jewelry.

But courts later ruled the raids were illegal — the police searched family members not under investigation — and in 1997 the city agreed to pay the Marks family $1.43 million to settle a civil-rights lawsuit.

Most Read Local Stories

- Finally, WA no longer has the nation’s most unfair tax system

- Seattle to Portland Amtrak train service suspended due to landslide

- Fixing the cormorant disaster on the Columbia: ‘How could this have come out any worse?’ WATCH

- Sound Transit reopens U District station after Israel-Hamas war protest

- Do redwood trees have a place in the future of WA’s forests? They’re already here

In 2000, Mr. Marks and his family became the subject of a documentary on PBS called “American Gypsy,” which detailed the legal fight.

For years, Mr. Marks attributed any bad news suffered by the city to his curse. Often he would go to City Council meetings to proclaim the curse was still active.

“I’m still bitter,” he told reporters earlier this month.

Mr. Marks became the leader of Spokane’s Romanian Gypsy community after the death of his father in 1997.

During his father’s funeral procession, Mr. Marks had the hearse stop at City Hall. He opened the door and invited his father’s spirit to forever live in City Hall. He said that was part of a “Gypsy curse” he had placed on the city.

A used-car salesman, Mr. Marks was a well-known figure around town, often wearing a hat, lots of jewelry and a necktie that advertised Tabasco sauce. The necktie was a reminder of the day when he came across a train crash that had left thousands of bottles of the spicy condiment spilled across the ground.

He bought every bottle for a penny each, then resold them to restaurants and bars for 15 cents each. The money helped launch his used-car business.

Romanian Gypsies migrated in large numbers to the United States around the turn of the 20th century to escape oppression. But many found new oppression here.

When the police raided the homes of Mr. Marks and his father in 1986, they searched more than two dozen family members who were at the homes — not just the four who were being investigated.

The Markses claimed that the $1.6 million in cash was being held for other Romanian families who did not trust banks, and they sued the city for $59 million.

A Spokane County Superior Court judge ruled that the searches were illegal and dismissed felony charges against the Markses. The Washington State Supreme Court later ordered the charges reinstated but said the evidence couldn’t be used at trial.

In 1996, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the police searches were too broad because they included people who weren’t targets of the investigation.

The case was settled after private negotiations.

Afterward, Mr. Marks said the settlement was a victory for the civil rights of a people who have been oppressed throughout history.

“I remember [Rosa Parks], the woman that said, ‘I’m tired of sitting at the end of the bus,’ I remember those little things. Jimmy Marks, the crazy Gypsy,” he told Jasmine Dellal, who made the PBS documentary.

“I’m tired of hiding out; I’m tired of moving on. My home was built in Spokane, Washington, and I wasn’t about to put it on roller skates and roll it down the highway,” Mr. Marks said.

+–+

Spokane — My old stompign grounds, and I met some of the Marks family while living there!!

Beautiful post ✍️

LikeLike

What a remarkable story of a fascinating people. Thank you.

LikeLike