Scott Ritter’s now talking about secondary education, literature, and fuck, what a White Scum Bucket Attitude he HAS . . . Give me Paul Robeson and Joe Hill & Elizabeth Gurely Flynn !!

This will have to be a quickie, but expect a ton more: My Comment to Jar Head Scott Ritter’s latest freaky Substack:

Fuck, this is so stupid, so dead, so racist, so White Man shit, it is embarassing. I have been teaching literature since 1983 in colleges — fucking GOnzaga, UT (Texas) NMSU, even fucking military at Fort Bliss and the NCO Academy at Biggs Field, and then, Fairchild, and then, WHite Sands, and then Seattle U, and then, many community colleges, including Clark College (Vancouver) PCC (Portland) Green River College, Seattle U, and many other places.

This guy has to shut the fuck up. Really. Stick to Bush and Iraq.

Embarassing.

How about The Crucible? How about Howard Zinn or Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, ot Eduardo Galeano, or, shit dog, this is ridiculous, this Jar Head.

Oh my, we work on Vietnam War, on the Korea War, on WWI and all the wars in Latin America. Poets, revolutionaries, and, yeah, sure, SInclair Lewis and Upton Sinclair and on and on and on. All of it we teach, in our classes, individually, ,but leave it to this guy to say, “I just don not know what they teach now.”

He has then fucks up Glen Ford (does he mean John Ford?).

Yeah, I write rant Substacks, sometime including my real journalism. But this shit?

He’s a fucking Reagan Republican. That fucking war criminal. Sad sad sad.

How about Hentry Miller’s The Crucible? Now that would be more apropos of the hell unleashed by the witch and communist and anti-Israel hunters in the dirty Trump et al gang, and then dirty Liz Cheney and Hillary and Jewish Hite House hole in the fucking Walling Wall gang — Yellen, Blinken, Garland, Kagan, Nuland, and, shit need I say more about the Jews who Want Arabs (Gazans) DOA.

Now, yes, Glen Ford rocks it!

Is jar head thinking about THAT Glen FOrd? Man, then he isn’t just a New York cracker.

Oh, this one: Gwyllyn Samuel Newton “Glenn” Ford (May 1, 1916 – August 30, 2006) was a Canadian-American actor who often portrayed ordinary men in unusual circumstances.

Thanks for more fucking stupid AmeriKKKan fodder to write about:

https://paulokirk.substack.com/p/my-clients-are-thrilled-they-get

+—+—+—+—+

Oh Well: Here, Ritter’s junk,

I don’t know what they are teaching today regarding literature in secondary education curriculum. I do know that a mainstay of such study back in the mid- to late-1970’s included John Steinbeck’s classic, The Grapes of Wrath. We read the book, and then watched Glen Ford’s cinematic rendition, starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad.

As the hard-luck everyman hero of Steinbeck’s tale of the Great Depression, Fonda came to symbolize all that America—and Americans—would, could, and should aspire to be: a defender of the oppressed, a fighter for the human detritus abandoned by an uncaring and unfeeling societal elite whose very essence contradicted the ostensible values of a nation, where the rights of the individual outweighed the dictate of the majority.

In 1995 Bruce Springsteen released an acoustic album, The Ghost of Tom Joad. The title track contained some of the most powerfully vivid lyrics ever written by a man known for his powerfully vivid lyrics. In 2008 Springsteen electrified the song, inviting Tom Morello, the lead guitarist for the American rock band Rage Against the Machine, to join him in performing The Ghost of Tom Joad live in concert.

The result was pure musical magic.

+—+

Springsteen? Fuck!

Enough! Scott Ritter is a product of the school of dead ideas.

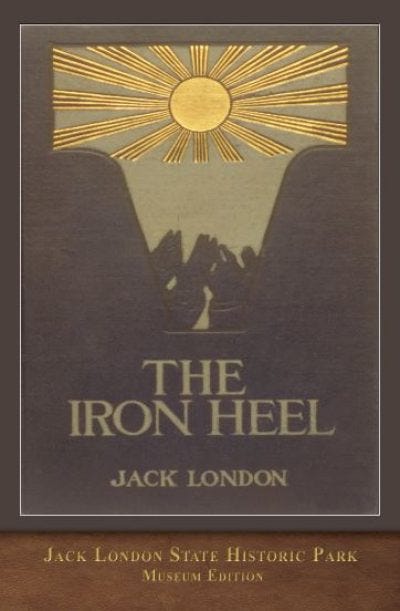

Jack London anyone?

Jack London presents a fictional “Everhard Manuscript”, hidden and found centuries in the future. This book is a platform for him to espouse his socialist views and predict the collapse of capitalism. Very different from his other action novels, it envisions a future oligarchic tyranny in America and the rise of the Socialist party. The book has been credited with influencing George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

How I Became A Socialist — London (1905)

It is quite fair to say that I became a Socialist in a fashion somewhat similar to the way in which the Teutonic pagans became Christians–it was hammered into me. Not only was I not looking for Socialism at the time of my conversion, but I was fighting it. I was very young and callow, did not know much of anything, and though I had never even heard of a school called “Individualism,” I sang the paean of the strong with all my heart.

This was because I was strong myself. By strong I mean that I had good health and hard muscles, both of which possessions are easily accounted for. I had lived my childhood on California ranches, my boyhood hustling newspapers on the streets of a healthy Western city, and my youth on the ozone-laden waters of San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. I loved life in the open, and I toiled in the open, at the hardest kinds of work. Learning no trade, but drifting along from job to job, I looked on the world and called it good, every bit of it. Let me repeat, this optimism was because I was healthy and strong, bothered with neither aches nor weaknesses, never turned down by the boss because I did not look fit, able always to get a job at shovelling coal, sailorizing, or manual labor of some sort.

And because of all this, exulting in my young life, able to hold my own at work or fight, I was a rampant individualist. It was very natural. I was a winner. Wherefore I called the game, as I saw it played, or thought I saw it played, a very proper game for MEN. To be a MAN was to write man in large capitals on my heart. To adventure like a man, and fight like a man, and do a man’s work (even for a boy’s pay)–these were things that reached right in and gripped hold of me as no other thing could. And I looked ahead into long vistas of a hazy and interminable future, into which, playing what I conceived to be MAN’S game, I should continue to travel with unfailing health, without accidents, and with muscles ever vigorous. As I say, this future was interminable. I could see myself only raging through life without end like one of Nietzsche’s blond-beasts, lustfully roving and conquering by sheer superiority and strength.

As for the unfortunates, the sick, and ailing, and old, and maimed, I must confess I hardly thought of them at all, save that I vaguely felt that they, barring accidents, could be as good as I if they wanted to real hard, and could work just as well. Accidents? Well, they represented FATE, also spelled out in capitals, and there was no getting around FATE. Napoleon had had an accident at Waterloo, but that did not dampen my desire to be another and later Napoleon. Further, the optimism bred of a stomach which could digest scrap iron and a body which flourished on hardships did not permit me to consider accidents as even remotely related to my glorious personality.

I hope I have made it clear that I was proud to be one of Nature’s strong-armed noblemen. The dignity of labor was to me the most impressive thing in the world. Without having read Carlyle, or Kipling, I formulated a gospel of work which put theirs in the shade. Work was everything. It was sanctification and salvation. The pride I took in a hard day’s work well done would be inconceivable to you. It is almost inconceivable to me as I look back upon it. I was as faithful a wage slave as ever capitalist exploited. To shirk or malinger on the man who paid me my wages was a sin, first, against myself, and second, against him. I considered it a crime second only to treason and just about as bad.

In short, my joyous individualism was dominated by the orthodox bourgeois ethics. I read the bourgeois papers, listened to the bourgeois preachers, and shouted at the sonorous platitudes of the bourgeois politicians. And I doubt not, if other events had not changed my career, that I should have evolved into a professional strike-breaker, (one of President Eliot’s American heroes), and had my head and my earning power irrevocably smashed by a club in the hands of some militant trades-unionist.

Just about this time, returning from a seven months’ voyage before the mast, and just turned eighteen, I took it into my head to go tramping. On rods and blind baggages I fought my way from the open West where men bucked big and the job hunted the man, to the congested labor centres of the East, where men were small potatoes and hunted the job for all they were worth. And on this new blond-beast adventure I found myself looking upon life from a new and totally different angle. I had dropped down from the proletariat into what sociologists love to call the “submerged tenth,” and I was startled to discover the way in which that submerged tenth was recruited.

I found there all sorts of men, many of whom had once been as good as myself and just as blond-beast; sailor-men, soldier-men, labor-men, all wrenched and distorted and twisted out of shape by toil and hardship and accident, and cast adrift by their masters like so many old horses. I battered on the drag and slammed back gates with them, or shivered with them in box cars and city parks, listening the while to life-histories which began under auspices as fair as mine, with digestions and bodies equal to and better than mine, and which ended there before my eyes in the shambles at the bottom of the Social Pit.

And as I listened my brain began to work. The woman of the streets and the man of the gutter drew very close to me. I saw the picture of the Social Pit as vividly as though it were a concrete thing, and at the bottom of the Pit I saw them, myself above them, not far, and hanging on to the slippery wall by main strength and sweat. And I confess a terror seized me. What when my strength failed? when I should be unable to work shoulder to shoulder with the strong men who were as yet babes unborn? And there and then I swore a great oath. It ran something like this: All my days I have worked hard with my body, and according to the number of days I have worked, by just that much am I nearer the bottom of the Pit. I shall climb out of the Pit, but not by the muscles of my body shall I climb out. I shall do no more hard work, and may God strike me dead if I do another day’s hard work with my body more than I absolutely have to do. And I have been busy ever since running away from hard work.

Incidentally, while tramping some ten thousand miles through the United States and Canada, I strayed into Niagara Falls, was nabbed by a fee-hunting constable, denied the right to plead guilty or not guilty, sentenced out of hand to thirty days’ imprisonment for having no fixed abode and no visible means of support, handcuffed and chained to a bunch of men similarly circumstanced, carted down country to Buffalo, registered at the Erie County Penitentiary, had my head clipped and my budding mustache shaved, was dressed in convict stripes, compulsorily vaccinated by a medical student who practised on such as we, made to march the lock-step, and put to work under the eyes of guards armed with Winchester rifles–all for adventuring in blond-beastly fashion. Concerning further details deponent sayeth not, though he may hint that some of his plethoric national patriotism simmered down and leaked out of the bottom of his soul somewhere–at least, since that experience he finds that he cares more for men and women and little children than for imaginary geographical lines.

* * * * * * *

To return to my conversion. I think it is apparent that my rampant individualism was pretty effectively hammered out of me, and something else as effectively hammered in. But, just as I had been an individualist without knowing it, I was now a Socialist without knowing it, withal, an unscientific one. I had been reborn, but not renamed, and I was running around to find out what manner of thing I was. I ran back to California and opened the books. I do not remember which ones I opened first. It is an unimportant detail anyway. I was already It, whatever It was, and by aid of the books I discovered that It was a Socialist. Since that day I have opened many books, but no economic argument, no lucid demonstration of the logic and inevitableness of Socialism affects me as profoundly and convincingly as I was affected on the day when I first saw the walls of the Social Pit rise around me and felt myself slipping down, down, into the shambles at the bottom.

THE END.

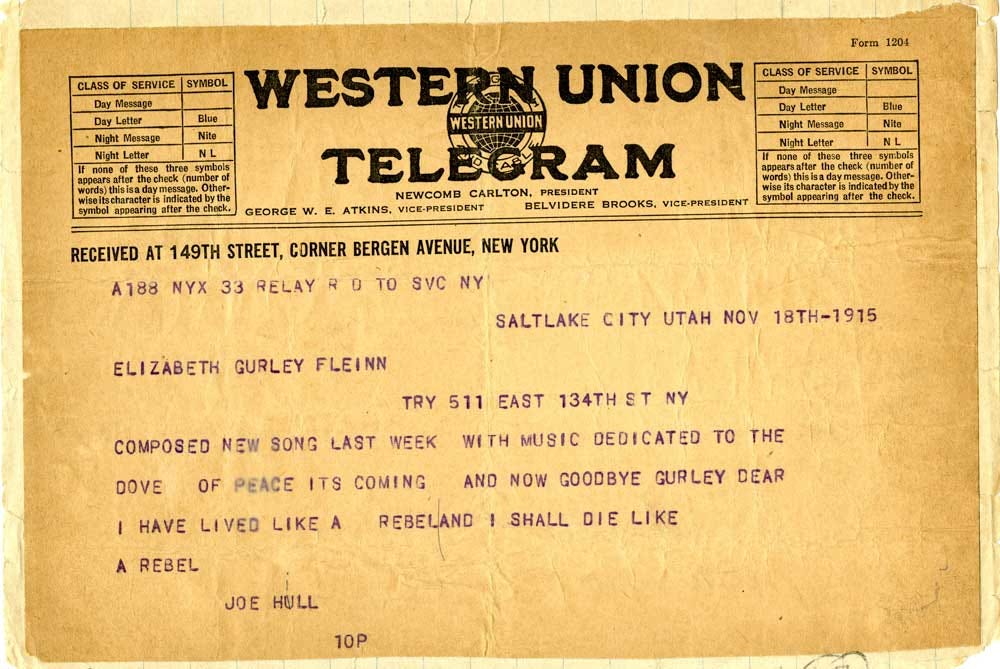

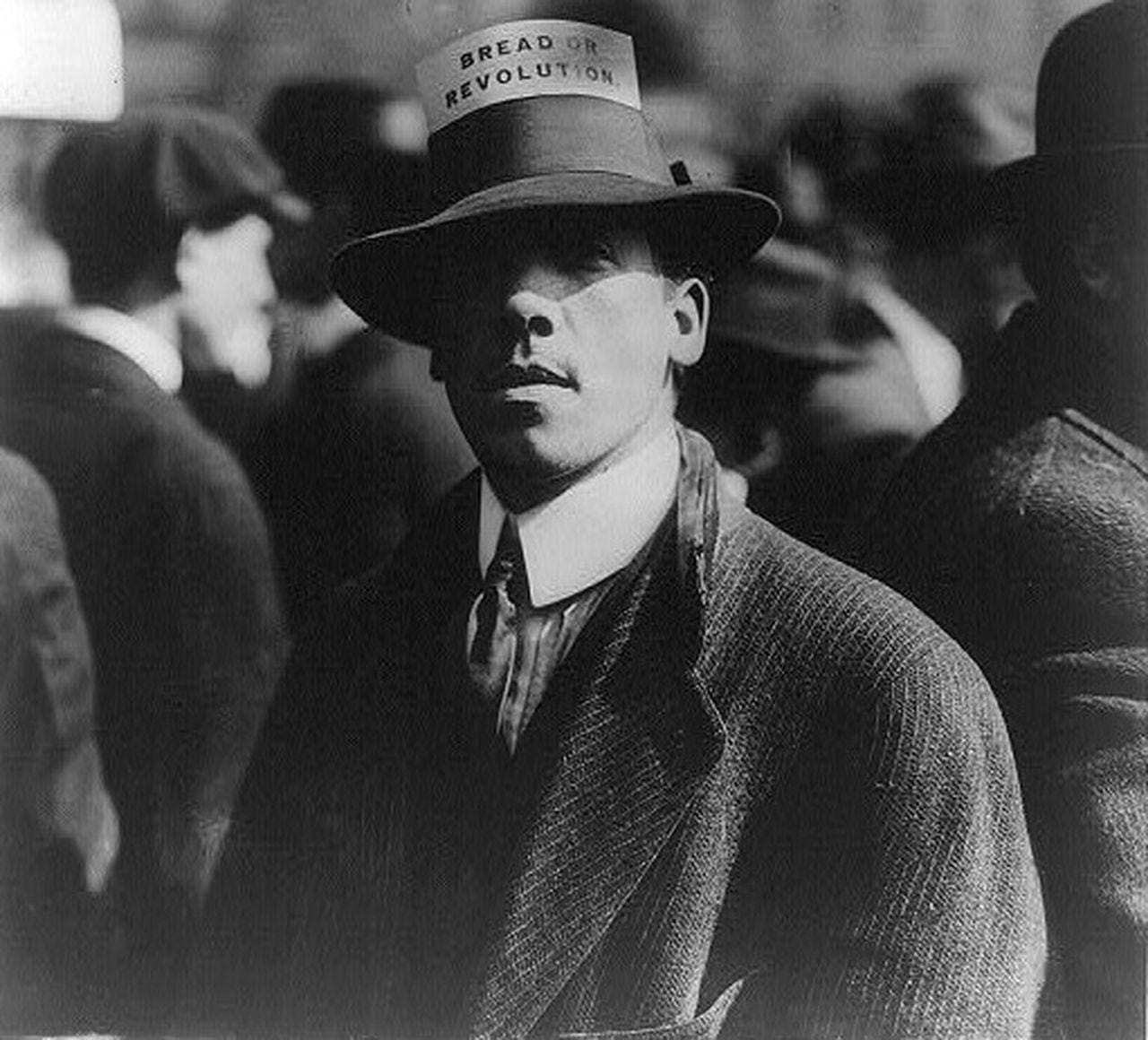

Here you go, Old Joe Hill:

Fucking Ritter, man, go away!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

At 7:00 a.m. on November 19, 1915, they shot Joe Hill, strapped to a chair, a target placed on his heart. Five sheriff’s deputies armed with rifles, four with live ammunition, one with blanks, stood ready.

“Aim” said the sheriff.

“Yes, aim,” said Hill.

Then it was over. Joe Hill — the Wobbly composer of revolutionary songs, the writer of revolutionary poems, an organizer on the docks of San Pedro, just thirty-six years old — was gone.

Joe Hill to some, Joe Hillstrom to others, was murdered that morning in Salt Lake City, a victim of Utah’s authorities — or was it the copper bosses?

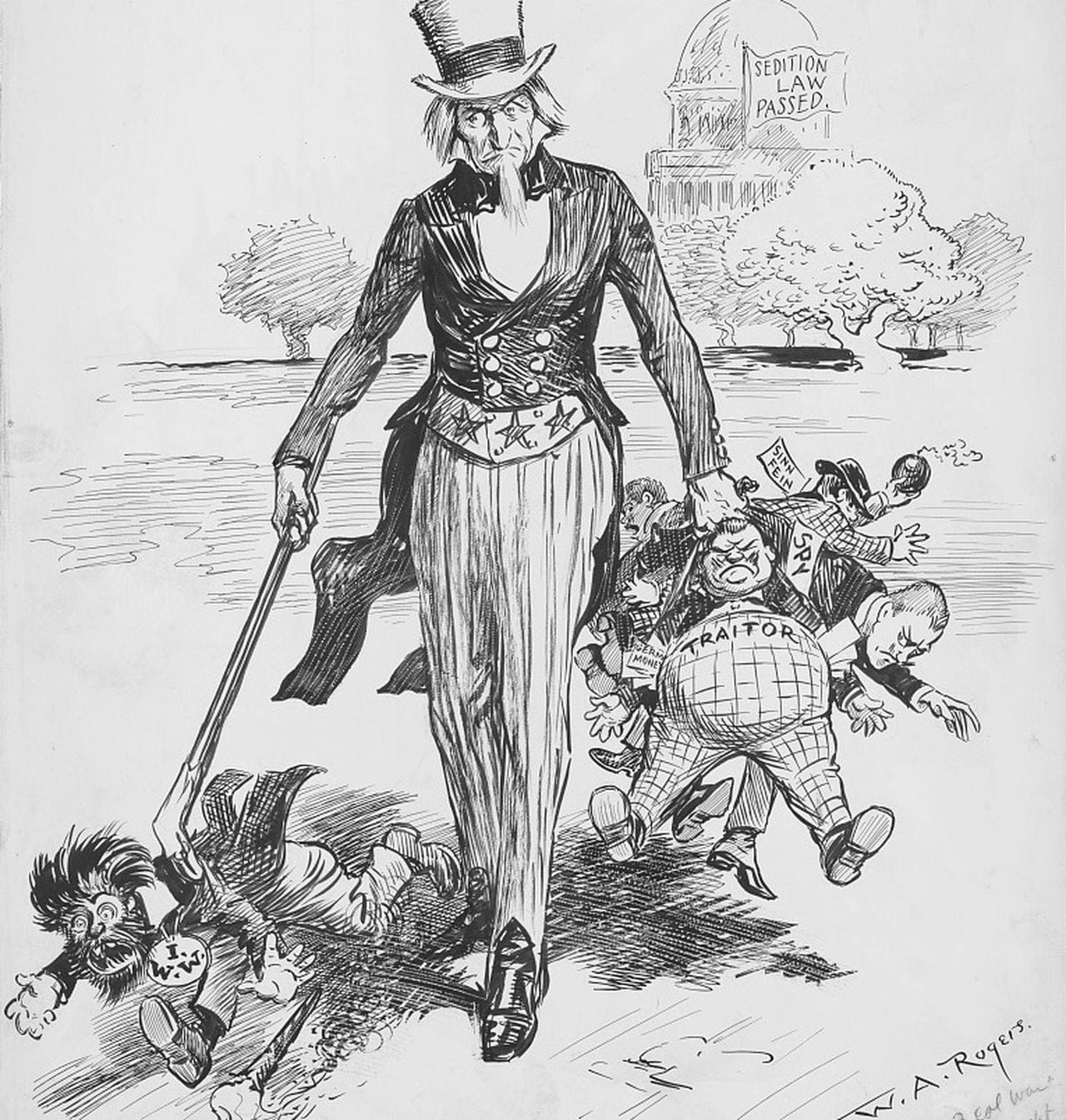

The movement to spare Joe Hill had been massive. Millions of workers spoke out demanding that he not be killed. Few, save the bosses themselves, could believe that Hill had shot the grocer John G. Morrison and his son Arling. Even the American Federation of Labor appealed on Hill’s behalf at its 1915 convention in San Francisco. Its president, Samuel Gompers, intensely hostile to the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), wired President Woodrow Wilson urging him to intervene; Wilson in turn appealed to William Spry, the governor of Utah. To no effect — the copper bosses would have their way.

Joe Hill’s remains were viewed by thousands in Salt Lake, then shipped back to Chicago. There, the Thanksgiving Day outpouring of grief and solidarity was like nothing seen before. In a packed West Side hall, there were speakers and singing. Bill Haywood, with his huge frame and one blazing eye, stood alone beside the casket and spoke for the IWW: “Goodbye Joe, you will live long in the hearts of the working class. Your songs will be sung wherever workers toil, urging them to organize.”

Ralph Chaplin, another Wobbly poet, composer of the labor anthem “Solidarity Forever,” reviewed the unimaginable day:

Slowly and impressively the vast throng moved through the west side streets. Windows flew open at its approach and were filled with peering faces. Porches and even roofs were blackened with people, and some of the more daring were lined up over signboards and on telephone and arc-light poles. The flower-bearers, with their bright colored floral pieces and wreaths tied with crimson ribbons, formed a walking garden almost a block in length. Thousands in the procession wore IWW pennants on their sleeves or red ribbons worded, “Joe Hill, murdered by the authorities of the state of Utah, November the 19th, 1915,” or, “Joe Hill, IWW martyr to a great cause,” “Don’t mourn — organize. Joe Hill,” and many others.

The Deseret Evening News struggled, it seems, for just what to say.

“What kind of man,” it asked, “is this whose death is celebrated with songs of revolt and who has at his bier more mourners than any prince or potentate?”

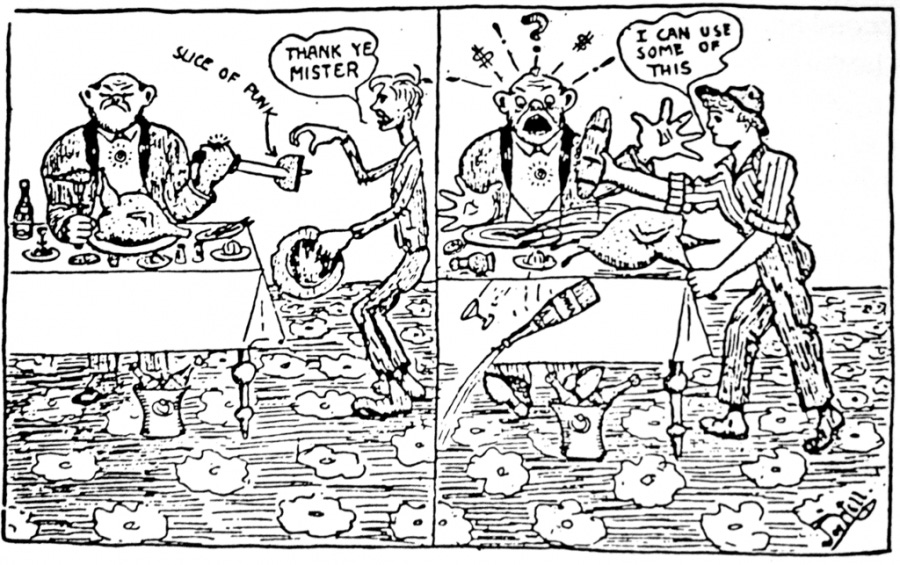

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn never had much use for politicians.

“My, how terribly embarrassing it must be to each of you to say all those nice things about yourself,” she quipped at a 1915 candidates forum that had seen a phalanx of Portland City Council hopefuls speak.

She then launched into a speech of her own, even though she wasn’t running for any office. “Labor,” she exclaimed, “is the foundation of society.”

“Either labor must rule or capital must rule,” she said in a speech at downtown’s Multnomah Hotel. “It’s a war for control, and we are quite frank about it.”

Four years after the Spokane upheaval, the I.W.W.’s fight for free speech reached the Rose City, when Mayor H. Russell Albee banned all “street speaking except religious speeches” in an effort to squash a strike at the Oregon Packing Co. on Southeast 8th Avenue at Belmont Street. The police told the strikers, most of whom were women, to “quit picketing, quit speaking, quit parading, or else face a jail sentence.” When the picketers still refused to disperse, a legion of mounted cops swooped in.

Flynn wasn’t involved in the strike at the Portland fruit cannery — she was back east leading silk-mill workers in New Jersey — but her friend Dr. Marie Equi waded into the fight and kept her apprised.

After helping to establish the American Civil Liberties Union, Flynn took up residence in Portland in the 1920s. By then she was suffering from persistent health problems. Long divorced from a Minnesota ore miner, she lived at Equi’s Southwest Portland home for years, too weak to rejoin the barricades. “I always felt I was in jail here,” she later said.

Nice 👌

LikeLike