Viva Pancho Villa Inside the Drawing Room of a Wild West Sanatorium

… brothers and sisters, can you spare a $5 for each serialized section? . . .

Go to my Substack and throw in a few literary shekels and get the next and the next and the complete novel serialized for your summer and fall enjoyment.

I go by Paulo Kirk over at Substack, since my Paul Haeder @ substack is sort of locked in limbo. Here, sign up for $5 a month and get the installments of the novel which I have just whet your appetited with below. PAULO KIRK

Share

Now for the $. Here, a novel, and you get it serialized. Any shekels for the author? Better than the shit storm of 98 percent of Netflix narratives you might stream. Way better than Oppenheimer crap at the movies. And, I will be writing the rest in real time. SERIALIZED.

The story is exploded narrative, dreams as dialogue, and animals of course think, so you get them thinking in this. Cast of characters?

Readers, come on, these are composits of real Paul K. Haeder people, in El Paso, Juarez, Chihuahua, real time and dream time. Get into it, and you will not be disappointed.

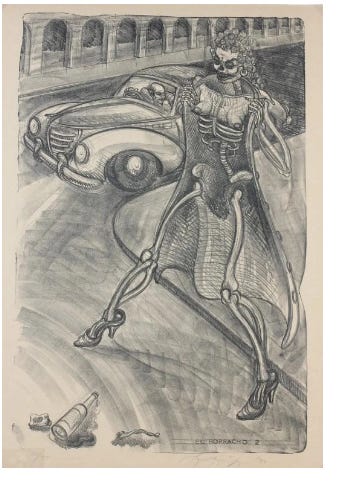

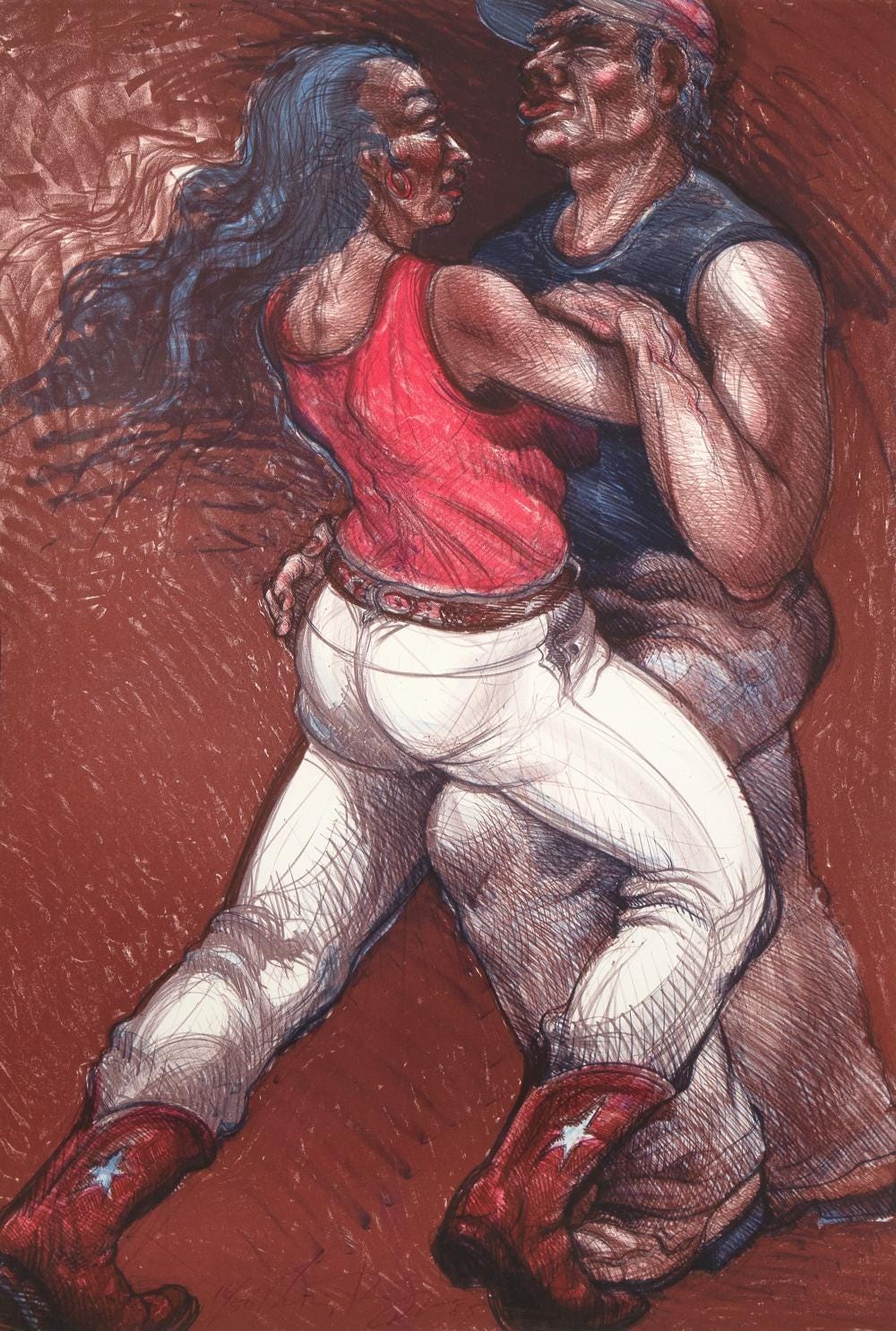

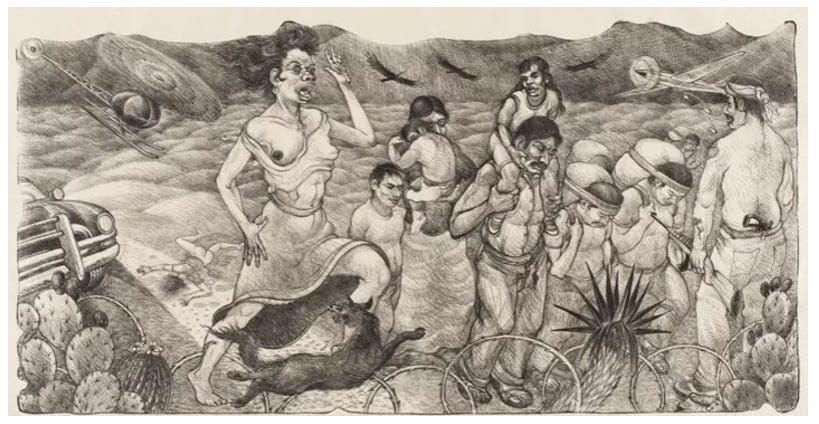

But it’s serialized, for a fee. The artwork is by Luis Jimenez, who I spent time with in Hondo, NM.

I have 70 pages written, and will kick it out for another 70 as we get some subscribers. So, today, you get a little of the style, the stream of consciousness, the wildness of the book.

I have no idea if anyone will Subscribe to my Substack, which means mullah, $5 a month, which means you get this novel, each week, but for today, just a taste. I need five? or ten? for a year subscription? That’s $5 times 12 months = $60. Brother and sister, can you spare a dime?

Book One: Viva Pancho Villa Inside the Drawing Room of a Wild West Sanatorium

Take One — Muralizing

Bambi watches two skippers – tall, flaco mini-skirted men-women of the night prancing up along the sidewalk leading to the Randolph Apartments. Transsexuals looking for the apartment “penthouse” across from Bambi’s digs.

She leans over the balcony, pulls on a Pall Mall, smiles at the two party animals drawn by the penthouse’s two inhabitants – George and Mike.

Fucking party hounds, George-Michael, she says, grabbing the plastic pint of shit-hole vodka from a Styrofoam cooler that looks like some mechanic’s carburetor dunking bath.

She points to the beer container: Dirty but keeps the juice iceee cold. You know me, chavo, ice cold but dirty.

Mario looks up at her, slowly, then back to his artist-drunk concentration in the waning light. Mario sits in front of a canvas. He’s sipping a tall boy, Pabst Blue Ribbon, and carving Prisma color curves around ink drawings of Diego Rivera, Frieda and his own likeness – big bulky back with neck-to-coccyx La Virgen de Guadalupe. It’s so big – the real tattoo – the one on Mario’s back the women artists he rolls with call it, Mario’s Protection Shroud.

Diego and Frieda are in her studio, some of her paintings in the background. Everything – Diego, the art, everything inside, including the big Mario artist in his own scene – is in black and white. Except for Frieda and her strokes on the back of Mario. The Virgin is half colored-in by Frieda. The rest of the saint’s image on Mario is black outline, like tattoo artists do in their artwork.

Mario’s waiting for Gregorio, best known as Greg the Yaqui. One of Many in Mario’s Protection Racket, that’s what some call the guys and gals who find him gigs in churches, at schools, anyplace for a two-story high mural. There are hangers on who want some of that wu, that energy from Mario the Quiet One, the Drunken Mexican Van Gough, the Plodding One with Paints and Sprays and Chiseling. Greg’s an artist – tattoos – and he writes songs, plays guitar and sells herba.

Gregorio, however, is the key to Mario’s band of merrymakers, in that MPR.

Long Indian hair, to his waist, Greg shouts up at the two on the balcony. Good evening, to you and to all the ghosts of the Randolph Apartments. Then he bows gallantly.

Greg’s bringing a couple of baggies of bud, but his avocation is writing down things in his journal. Nice hefty notepad sheathed by fine soft deerskin cover. He takes postcards, beer labels, receipts, notes, anything he comes across in his walkabout. He glues them in, draws around them, and he writes down conversations, words, noting the color of the sky, and the species of birds lingering on ledges and in the air. Names of people he drinks with, and ways people laugh it up when they get high with him.

I’m on my way up, boys and girls. Por supuesto.

He tips his floppy cowboy hat – a good handful of feathers like pickets around the hat’s belt sometimes leaves a Mardi Gras feel — to the two cross-dressers who reach the one entryway to the two-building complex. May the light of that moon over Juarez shine a bright beam of luck onto both of you.

One of the guys smiles, while the other just shouts, Oh my God, a real Indian Cowboy. Cowboy Indian? Whichever you prefer, handsome.

He lets them both into the courtyard first. I prefer, Gregorio the Gregarious Poet. He lifts up the journal from his old Army pack. Writing now, in my head, what crazy things you two might be up to. Pen to paper soon.

If you want first-person reportage, then join us with George Michael. This is the red-wigged one, with purple everything – eyelashes, toenails and fingernails, and sequined mini skirt with blousy blouse. The courtyard is tiled, a small cherub-holding a basin as the loud fountain at the center, shaded by leafy locus trees, soft yuccas and germaniums in clay crumbling pots. Sparrows, starlings and a few crows hide out in luscious gardenia trees – eight of them placed in the courtyard near wrought iron chairs and love seats. Doves high above on electrical lines jerk and poke the air below. Pigeons on the horizon — a dozen – swarm, circling in unison.

The two girl-boys walk up the winding exterior stairway to the George Michael Penthouse. Greg jots down notes – Little flock of pigeons. Twelve. All banded. Looks like from over the Rio Grande. Making some haste. Goddamn, I have to give it to the narcos. Trained pigeons, mules with wings, dropping off whatever. Heroin. PCP. Coke.

He draws a pigeon on one side of his notes, a pigeon with a donkey body. A mule with wings dove wings. Flying over the Rio Grande. Bail of pot dangling from what are now talons.

Slash of blood and puke/effluent of heaving sex/ chemical confusion/river of hope/river of sangre/ ever waiting, brothers/sisters fleeing/ this barfed up Yankeedom/ flocking for some dream/ a song under breath/ cleaning roofing cooking/ mules and worker bees/ river of Uncle Sam’s soldiers/ song of mariachi/ hot nights of fornication . . . .

Neruda, get your ass up here and serve us. Pronto. Bambi goes inside the apartment after barking her orders, and within the riot of all assorted masks covering every inch of wall space, mostly from Mexico, and all the clay pots (some glazed and others rough and raw like 700-year-old Olmec specimens) and paper mache skeletons and dancing devils and angels, she goes to one of her more prized possessions – authentic Zapotec pot of a dog on hind legs, the belly the open pint-sized pot. She pulls out two 20s, smells them, touches the white cocaine crusty drivel with tongue-moistened fingers, and touches fingers to her gums.

Ritual, darling, ritual. Mario looks in from outside, where he is with painting, beer and warm breezes of El Paso. He smiles, then shakes his head. Waste not want not, pintor, she says laughing.

The hot white and yellow bulb lights of Juarez are twinkling through the few tall pines in their neighborhood. Or, that is, Bambi’s neighborhood. She’s always open to Mario doing some painting here – and in a blue moon — letting him crash on old Navajo blankets and pillows. No matter how well connected Mario’s murals get him in terms of celebrity status in the neighborhoods, and how well his virgins are loved by the El Paso Catholic diocese, he is virtually homeless – finding garages and storage units in disuse to crash in. A week, a month, that’s about it.

Greg has a wife and kid, and ever since he got clean and sober from intravenous heroin use, he is considered somewhat of a triumph. Five years in prison, Huntsville, he went back to his wife, Sonya, and his daughter Drew. Sonya’s an RN, has good health insurance, and Greg does 30 or more hours a week at Sonya’s brother’s body and paint shop. Mario sometimes gets gigs at the Auto Reforma Clinica, and while Sonya and Drew love Mario, the portly painter has never resorted to asking for their place to crash after some hard days and weeks roughing it in an unplumbed hot garage.

Bambi teaches microbiology and creative writing at the university – part-time – so she stitches a living from finding rare antiquities in Mexico, and sometimes she finds less rare valium and other prescriptions and brings them over the border for the party animals in the legal and medical realm.

It’s all in translation, she says, flipping an elbow onto Gregorio’s arm. Gregorio is watching Mario and his four by two foot painting.

Hey, so? Mario turns and smiles. This going to satisfy your doctor friend?

You know, you know . . . Unreal. She’ll love it, really. With all those Madonna retablos, what have you, and the saints and weird day of the dead stuff, this will stand out. How much, hmm?

That’s your part. Isn’t that your scene. Mario looks at the images, then takes a slug of beer.

But, that’s putting a lot on everyone else, compadre. Setting the price, and all this negotiation, how can you know ever if the price is right? There is the business of art, and nine out of ten times – more than nine, how about nine point nine out of ten times, the artist gets royally screwed.

He nods, and then burps before speaking. Ha. When’s the next bowl of mota coming? When’s the next art opening with victuals, and when is that eighteen pack on the horizon? He lifts the can, and draws down again.

That is the Van Gough question, no? How many times can artists get screwed by their own family, their own generation?

Nice putting me in with Vincent. I’ve been in Iowa and Nebraska, traveling with a crew, painting grain elevators. Good people, but no one wanted a religious or political mural from me, though in Colorado there is a co-op or something like a hippie grocery store that paid me in food and get-out-of-Colorado money to take a bus back here. A big wall, with lots of produce, fields, big strong women and men, and they let me go with Asians. Japanese truck farmers. And braceros, too. Even there, the Virgin is on the back of one of the farm hands. Even on those silos, I put the virgin in a corner, or ledge, way up high, where only a worker could see her.

Bambi gives him a pat on the back. Yep, that’s the story to end all stories. Mario crisscrossing the country painting grotesque grain elevators with a bunch of other Mexicans, and little do the rednecks know, the Virgin is high up – probably the highest point on those wheat fields – supplication for you, brother artist. Now that’s a fucking story that needs to be broadcast by Connie Chung or some such shit.

Greg starts strumming his guitar. Smoke swirls around his long locks. He coughs before . . . singing:

They ride the railroads, modern troubadours and painters, the stage is their canvas, vast open lands conquered by the pink clan, but still, flocks of birds – crows – they sing to ancient brothers, even the mixed blood Spanish and Indios . . . paints in a backpack, beer in the shade, they cover the land with few words, lots of laughs, the hard stare down of the sun, as they work to pay for the next run, in their cups, they are in the night, lightning cutting across plains, the vibrant sky wailing for aunties and fathers, warriors, the Ghost Dancers, all of them singing in the storms, the rush of monsoons, that Mexican guy, they say, paints up a storm, and look what he does up high . . . Catholic talisman, Mother of us All, the Virgin, mother of the narcos and priests, calming woman of the aristocrat and the gang banger, these stories are locked inside each brush stroke, the Mexican thinks harder than they do, but he is lost, poor son of a bitch, looking for his next burrito and beer, he’s got the Virgin, he’s got the crown of thorns, he’s got his feet on one side of the land, Mexico, and the other in the Brave River, Rio Bravo, Grand to the Gringo.

Or, I can recite it to one of those creative writing classes you muck with, Bambi, without Waylon Jennings meets Flaco Jimenez guitar:

My Son, Mi Hijo

wild hombres ride the rails

drunken, fornicating troubadours and painters

the canvas is their stage is their world

canyons and open prairies

the pink clan think they conquered

still, murders of crows sing

ancient brothers

those mixed ones, Mestizo

these guys have paints

rainbow making things in backpacks

don’t confuse beer in shade

as slovenliness

artists cover the land with few words

hyena laughs

fire pits, then another day

staring down the sun

they work to pay for the next run

already in their cups eleven am

they are philosophers of night

lightning cutting across plains

vibrant sky wailing ‘aunties and fathers,

warriors, the Ghost Dancers, come

home’, singing sandstorms

then a rush of monsoons

that Mexican guy, they say,

paints up a storm

look what he paints up high

his Catholic icon, voodoo

he says, Mother of us All, the Virgin,

mother of the narcos and priests,

calming woman of the aristocrat

gang banger’s mother

stories locked inside each brush stroke

the Mexican thinks harder

than they do, but he is lost

poor son of a bitch

looking for his next burrito and beer

he’s got the Virgin fever

he’s got his own crown of thorns

he’s got one foot on one side

Tortilla curtain

Mexico, and the other

in the Brave River, El Rio Bravo,

Rio Grand to the Gringo

The Mexican to the Midwesterner

The Muralist to his amigos

and to the Virgin, My Son.

Mario stands, finishes the tall boy, and applauds. Bambi claps. She is writing down what she can from Gregorio’s epic Mario-Virgin poem, though he has quite a few of them already written and performed.

So, now, we prepare for Tom Connelly. Prepare the tequila. Get your horse-riding britches ready. Let’s get there before the sun sets, before Tommy turns into an albino vampire. Messing with rattlesnakes, ain’t my cup of tequila, boys, but riding an Arabian, yessiree, sensuous.

+–+