oh, red nation, Turtle Islander, cry for brother bear and crow and the Heart of the Monster

A Tribe Once Called – “Power from the Brain” Paul Haeder, 10 years Ago?

And so it goes — wheat, King Wheat, and screw the tribes, those tribes!

Breaching the four lower Snake River dams would put thousands of Pacific Northwest farmers at risk, a new report from the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association states.

About 7,644 farms in the affected area generate approximately $2 billion in annual sales.

Small to medium-sized farms would be most at risk, according to agricultural stakeholders.

So, those Snake River dams damned the wild salmon, killed the genetic line, and alas, we are in this constant strain, this constant Oh Pioneers and Oh Those Farmers Oh Those Monroe Doctrine buds, those Oh Isn’t Economy of Scale Predatory Capitialism fine adherents, to Oh the Victors Write the History Books and Law So Get Over It Injuns kinda folk point in time where the ethics, which were already threadbare early in AmeriKKKa’s history, are melting away.

“Well, fish buyers who had pretended to have good relations with such fisheries as the Tulalips and the Lummis . . . , they said. . . , ‘We aren’t going to sell your fishermen gasoline anymore from our docks. We aren’t going to supply ice for the fish that you take into the hulls of your boats.’

And so there was all these things and the state of Washington stood behind them on that, saying, ‘Well, the Boldt Decision isn’t really in effect until the Supreme Court upholds it.'”

Hank Adams ( Assiniboine-Sioux of Fort Peck Tribes ), NMAI Interview, July 2016

And, of course, these are not biodynamic farmers, you know, farmers growing food for USA, but these a grain gulags, wheat and oats and soya and all those cereals and grains that make not our world go around, but make the Monsantos and Cargills and ADM’s and . . . [Kraft, Coca-Cola, Nestle, P&G, Johnson & Johnson, Unilever, Pepsico, General Mills inc, Kellogg’s, and Mars] and all those Mafia’s [ 4 U.S. companies alone–Monsanto, Syngenta, DuPont, and DaAgro Sciences–control 80% of the corn market, 70% of the soybean market, and more than 50% of global seed supply.]

Here, 18 years ago, fools:

Flat-Earther Bush’s Style for Wild Salmon (Part III of III) — II & I

Saving Salmon, Saving Grace — Busting Dams

by Paul Haeder www.dissidentvoice.org August 31, 2005

“[T]hese Falls, which have fallen further, which sit dry

and quiet as a graveyard now? These Falls are that place

where ghosts of salmon jump, where ghosts of women mourn

their children who will never find their way back home…”— Sherman Alexie, from “The Place Where Ghosts of Salmon Jump”

One of the greatest contrasts for area residents is how the river Spokane is so powerfully sculpted by nature yet so disembodied from its recent past. The Children of the Sun tribe less than 70 years ago made great snatches of Chinook and Coho near where the Maple Street Bridge funnels SUVs and trucks in an endless stream of belching metal.

Sherman Alexie, best known for Smoke Signals and The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, and a member of the Spokane tribe, does more than lament the loss of the salmon runs. He is confrontational and “in the face” of corporate and political forces that deem salmon as “a fish of diminishing value.”

For Alexie and Spokane tribal elder Pauline Flett, and for groups like Salmon for All and Save Our Wild Salmon, it’s a no-brainer to bring back the clear waters and an abundance of native fish to a river like the Spokane and a river system like the Columbia/Snake.

For some Northwest salmon people, such as Grey Owl, a Southern Cheyenne artist and cultural guide living on the Nez Perce reservation, river and subsequent fish contamination means early, hard deaths.

“Even supposing that we exclude some nefarious government plot to study them,” Grey Owl said, “it is certainly not beyond the realm of possibility that the government was not as careful in the ‘60s about what Hanford released, including radioactive water used to cool the reaction, into the Columbia. Just in our small little Native community here, all salmon people, there is a high incidence of cancers, tumors, and unexplained cysts.”

For salmon and salmon people — including various Inland West and Pacific Coast tribes and non-tribal commercial and recreational fishermen — they recognize three pivotal river systems that incubate and release salmon into the Pacific for the world to enjoy. The Sacramento, Yukon and Columbia/Snake systems are the genetic conveyor belts of wild salmon. For many, these river systems must be unleashed, free of mining and agricultural bleed-offs, and set in riparian and forest cover where clear-cutting is a long-vanished 1900s technology.

More than 45 local, regional and state organizations make up a coalition supporting breaching four dams on the lower Snake River: Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite.

‘A world where the salmon cannot live may be a world in which man cannot live either.” Anthony Netboy, The Salmon: Their Fight for Survival

Groups like Friends of the Earth, Trout Unlimited, Northwest Sportfishing Industries Association, American Rivers, NW Energy Coalition, Sierra Club, Earthjustice, Washington Trollers Association make up a cadre of lobbying, informational and advocacy groups poised to support bringing down the four dams.

Save Our Wild Salmon (SOS), as part of the coalition’s main group pushing dam removal, focuses specifically on restoring salmon in the Snake River. Kell McAboy, three years in the trenches as Eastern Washington organizer for SOS in Spokane, has been a vocal public protector of the Snake River and its salmon.

“When thinking about removing the four dams in the lower Snake River, not only is it the best bet for the salmon, it’s the best bet for people. There are more than 200 dams in the Columbia Basin, making it the most constipated watershed on earth.”

The main issues McAboy and others in the coalition see as their stumbling blocks are transportation, farmers and the mythology of having an inland seaport at Lewiston, 900 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean.

“The issue comes down to transportation,” McAboy says. She noted that rail and eighteen-wheeler transportation links can be revitalized in order to move the wheat and other goods the current barges on the dammed Snake provide.

As part of her duties with SOS, McAboy has organized tours of the Snake River, the four dams and free-flowing rivers like the Clearwater and Salmon. Her organization and the coalition at large are connected to a non-profit group, LightHawk, which has planes and pilots at the ready to take people into the air so they might see the environmental impact of dammed rivers from aloft.

“From the air, the people get a unique perspective of how a free-flowing river and the impounded river look like,” McAboy said.

It’s clear when one starts looking at this “to breach or not to breach” debate that there is a definite dichotomy between east and west Washington. Most people for breaching have zip codes set west of the Cascades, while those opposed are from the Inland Northwest.

One strategy Jill Wasberg from SOS in Seattle sees as a way to put flesh and bone on those everyday people who have lost livelihoods and cultural connections because of the death of the natural, large salmon runs, is to foster a sense of story — a narrative lynchpin so the pro-dam breaching stakeholders in this “Save Our Dams” versus “Save Our Salmon” gain voice.

She and others in SOS — with offices in Portland, Seattle, Washington D.C. and Spokane — are interviewing people for a video and publication venture called “The Stories Project.” Wasberg hopes to capture the history, cultural identity and economic value.

Bill Kelley, professor in Eastern Washington University’s Urban and Regional Planning Program, promotes an on-going dialogue “about what constitutes community.” Kelley stresses that a definition of ecology — including river and salmon recovery — should include a “place for humans [and] their needs and desires in balance with ecological capacities.”

“I worry that when our passionate advocacy is too shrill and when our science and comprehensive planning, with all of its complexity, can’t be illustrated in simple and compelling and human terms,” Kelley said, “that we turn off our citizens when we most need to be turning them on.”

As EWU professor, Kelley coordinates undergraduate and graduate students in projects with various communities and constituencies to help them decide how their rural and undeveloped land and their urban space can give them a sense of stewardship and self-determination.

More than 85 rapids and falls will reappear on the Snake River if the dams are removed, McAboy notes. This will result in thrusting volumes of water and no more fattened impounded pools where salmon face nigh nitrogen loads, bacteria and viruses, longer journeys back to the Pacific estuaries, and unnaturally warm waters. Cold, fast-flowing water will push salmon smolt out to sea as nature designed.

Many biologists see breaching and habitat recovery as the only credible salvation to regenerating wild salmon stocks to numbers where sustainability occurs. If breaching is finally approved as the best, most prudent and eventually the most economically sane solution, the four main barriers will be gone, allowing 140 miles of the main stem of the Snake to open up.

This in turn will free hundreds of miles of tributaries in Eastern Washington, Idaho, Oregon and Wyoming for salmon to return full of sperm and roe to breed hundreds of millions of fry that will live and die, leaving millions to transmogrify into river-loving fry and estuary-seeking smolt. Most salmon return to and live in oceans, either close to shore or thousands of miles out to sea, for two to seven years before the evolutionary switch clicks on to return to their gravel beds.

Dave Johnson is a passionate fisheries scientist with the Nez Perce tribe who works to refine and harmonize a dozen tribal hatcheries as a way of supplementing the wild salmon that have been cut off since the Snake River dams came on line in the 1960s and ‘70s. For Johnson, his tribe and others have “a right to fish in all those streams.”

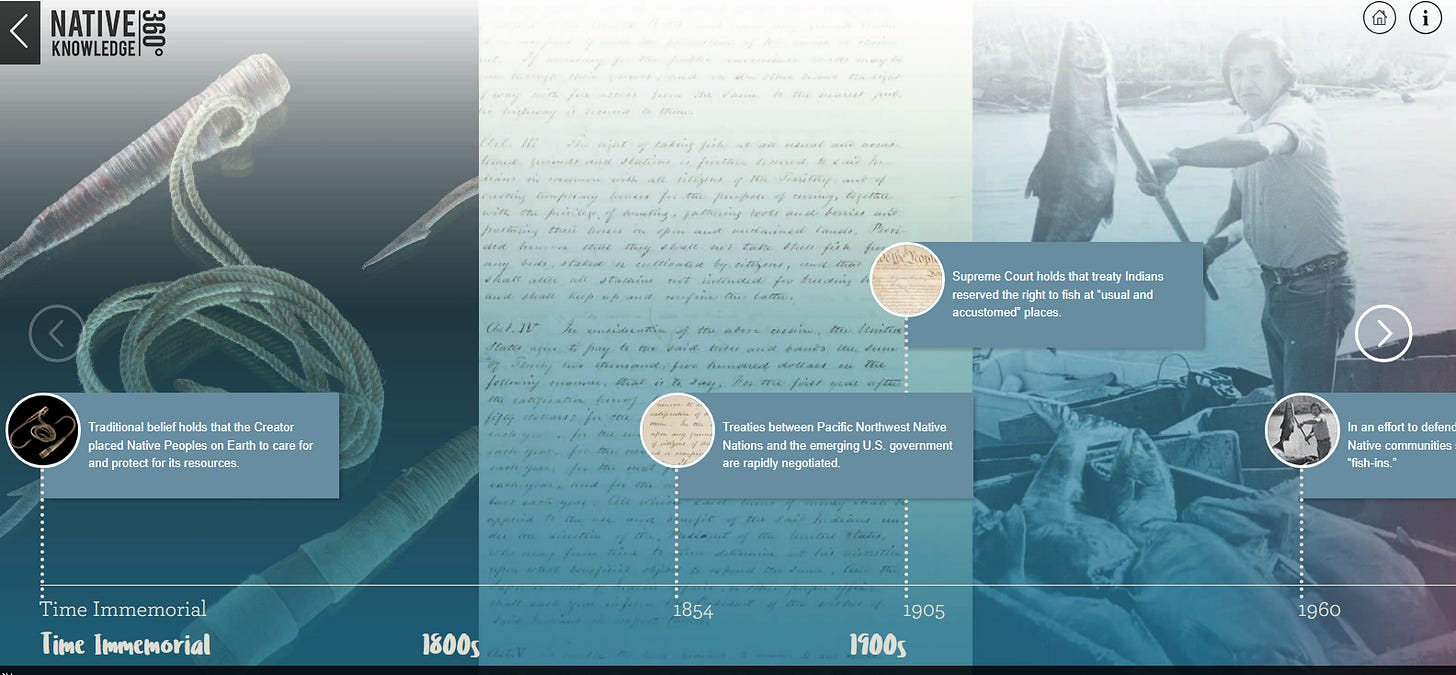

There seems to be a card up the sleeve of various Northwest tribes, including the Nez Perce. “The Nez Perce are not just some historical artifact,” said David Cummings, Nez Perce legal counsel. Cummings notes that the courts system is just one of several tools; yet treaties signed 1855 and 1856 with tribes of the Washington Coast, Puget Sound and Columbia River stated that while tribes ceded most of their land (1.34 million acres compared to the current 750,000 for just the Nez Perce tribe, as an example), those treaties gave exclusive rights to fish within their reservations and rights to fish at “all usual and accustomed places . . . in common with citizens.”

For Cummings, the 1974 “Boldt Decision” reaffirming tribal rights to 50 percent of the harvestable fish “destined for tribal usual and accustomed fishing grounds” is sort of a cultural and environmental ace in the hole.

Cummings notes that the treaty carries with it a right to restoration of wildlife, including the riverine ecosystem and water quality.

There is a genetic, dietary, and cultural connection to salmon and sustainable harvests. Johnson is one of more than 200 scientists who advocate breaching the four lower Snake dams.

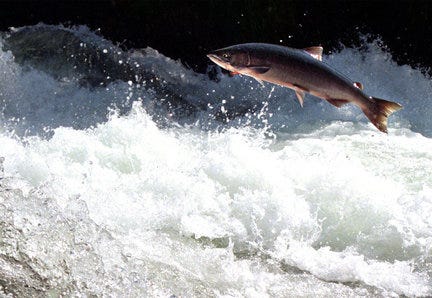

Pacific Northwest salmon for a million years have struggled to recreate their genes by leaving salt water to go upstream. By the millions, wild Coho, Chinook, sockeye, pink, chum, King and others had returned in their respective fall, summer and spring runs. The wild salmon of the Columbia drove their fasting bodies through scablands, falls, and heat to return to their birthing riffles more than 900 miles inland from the Pacific to Eastern Washington and Oregon and deep into Idaho and Wyoming.

That was before the eight federal dams that are the gauntlet stopping the Inland West’s salmon from spawning.

The parallel struggle of overcoming obstacles — now dams — that anadromous fish and the tribes of the Northwest share is telling.

For 10,000 years, Indian tribes rendezvoused at the lower Columbia River’s Celilo Falls. Traders from as far away as Central America gathered with thousands of others from dozens of tribes.

Fast-forward a few thousand years to the Lewis and Clark Expedition as Clark comments on the hundreds of thousands of salmon they came across: “The multitude of this fish. The water is so clear that they can readily be seen at a depth of 115 or 120 feet. But at this season they float in such quantities down the stream the Indians have only to collect, split and dry them on the scaffolds.”

The Dalles dam in 1956 impounded the river, mucked up the cascades and free-flowing nature of things, and inundated the sacred Celilo Falls.

The four lower Columbia dams have been technologically manipulated to allow for safer passage of salmon running to the spawning beds and to allow the smolts to be flushed more safely to sea. The process for the lower Snake River dams, however, is more daunting and less technologically successful.

Most of this country’s 75,000 dams were pounded, cemented and erected into the paths of ancient free-flowing rivers before humans, especially at the political level, saw the big picture of negative biological, cultural and economic impacts of this river-jamming technology, notes Lizzie Grossman, author of the book, Watershed: The Undamming of America.

Grossman read from her just published book at Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane on July 29, emphasizing how “in the past ten years people all over the country have been looking at waterways — how their local creek or river was ignored and abused.” There is a strong sense of wanting the rivers back, including breaching dams.

“America has spent most of its first two centuries turning its rivers into highways, ditches and power plants,” Grossman states. “Now, slowly, we are relearning what a river is and how to live with one. . . . Reconsidering the use of our rivers means examining our priorities as a nation. It forces us to rethink our patterns of consumption and growth and may well be the key to reclaiming a vital part of America’s future.”

“A dam can disrupt a river’s entire ecosystem, affecting everything from headwaters to delta,” Grossman puts into her book’s Forward. “So removing a dam, large or small, is not an easy process. . . . Dam removal alters the visual contours of a community. It is a very public enterprise and is almost always controversial, involving political decisions and civic debate.”

A hodgepodge of liberal environmental and politically conservative groups is pushing to gain political support for the Salmon Planning Act, which states that dam breaching is an option if all other routes to wild salmon species and habitat recovery fail to generate sustainable, healthy levels.

The executive director of Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association, Liz Hamilton, sees dam breaching from a died-in-the-wool capitalist point of view. Her own Republican Party roots and her membership’s conservative bent belie a dynamic most people do not associate with endangered species causes.

“Our industry lost 10,000 jobs in the northwest,” she noted as a consequence of the construction of the eight dams. “Fear mongers have led this issue: ‘If we don’t breach, every single salmon will die.’ On the other side, we’ve heard, ‘If we do breach, we will lose our jobs and way of life.’”

Hamilton sees her group and the coalition’s biggest challenge to convince people of the economic and cultural benefits of breaching dams as psychological. “People fear change. People have to see a future. If they don’t see themselves in it, your average citizen will not respond.”

Hamilton knows salmon restoration is costly. But she sees the Snake River system as a thousand miles of nearly pristine spawning habitat. Hamilton and her coalition lobby people to see a future many resist: removal of the four Snake River dams. “Without the dams we can still transport wheat. We can still generate electricity. We can still irrigate crops. The pressures that people put on the land will still be there when the dams are removed. . . . The cheapest thing to do is unblock a blocked culvert.”

The General Accounting Office reported that more than $3.3 billion in taxpayers’ money was spent by more than a dozen agencies the past 20 years to try and mitigate declines in Columbia River basin salmon runs. On top of that, tens-of-millions have also been spent by state and local governments.

This waste of money has paid for ill-conceived measures and technologies to try and help the fish survive the dams — 34 years of barging fish around dams. Snake River sockeye, Chinook salmon and steelhead were granted “protection” in 1991, ’92, and ’97 respectively through the Endangered Species Act.

Hatcheries have produced more than 90 percent of 2001 salmon and steelhead. Hatchery salmon are not the goal for the diverse environmental and scientific communities because of various issues, including disease, weak genetic lines, and stifling of biodiversity in its natural state. If wild salmon are not rejuvenated, many predict that by 2017 several indigenous populations will become extinct.

Additionally, RAND, a conservative “think tank,” completed a report in September 2002 that posits dam removal on the lower Snake will not bring with it economic turmoil. In fact, the RAND report shows how 10,000 long-term jobs might very well be created and centered right in the economically hard-hit communities that make up the Inland Empire.

Remove dams and help create livable wage jobs and revive a weak Inland Empire economy while preserving sustainable and abundant salmon? The answer seems obvious to most, but for those who resist, there is the 1855 treaty and Boldt decision which cost U.S. taxpayers upwards of $10 to $60 billion paid to the tribes for destroying their salmon and habitat.

“The salmon are our relatives,” Grey Owl said. “The salmon are of this land just as we are. We both share a connection to this land that is hardwired into our DNA. They teach us many spiritual lessons such as the circle of life, giving of yourself to help others, and that our life’s purpose should be to help someone else live.”

Paul K. Haeder teaches college at Spokane Falls Community College and other places. He is a former daily newspaper journalist in Arizona and Texas, whose independent work has appeared in many publications. As a book reviewer for the El Paso Times, many of his reviews appeared in other Gannett newspapers.

+—+

Haeder: Fish Farm Foul

“He [Judge Boldt] was threatened, he was harassed, but his case went all the way to the Supreme Court and was upheld. And what Judge Boldt did and what the Supreme Court did was not give rights in those cases, they affirmed them. In other words, they said these rights are there.”

Elizabeth Furse, former U.S. Representative from Oregon, NMAI Interview, August 2017.

Check the history of “those dams.” FISH WARS = Source.

[Photo: Heart of the Monster]

Flat-Earther Bush’s Style for Wild Salmon (Part II of III)

History of Salmon as Microcosm: Humans’ Out-of-Whack Carrying Capacity, and Failure to Grasp Earth’s Biological Web

by Paul Haeder/ http://www.dissidentvoice.org / August 12, 2005

As climate cooled 40 to 20 million years ago, streams and rivers decreased in nutrient productivity, and so the sciences says that freshwater fish went anadromous and developed a sea-going life cycle as oceans became rich sources of food.

In this part of the America, the salmon’s evolution linked and adapted to the changes in topography. For millions of years salmon have been here in abundance. In the past 100 years, human evolution in the Pacific Northwest has brought some species of salmon to extinction and has impoverished the continued existence of a sustainable salmon ecosystem.

Salmon have been part of the lifeblood of peoples from Finland, Ireland, Norway, Russia, to Japan and British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. Salmon sustain the life of a forest, and this species is the link in the natural gear work and framework of an ecosystem that has grown because of the returning spawning salmon.

From the nitrogen in grizzlies’ bones and hair, to the nitrogen in valley-bottom forests, and nutrients fed to gargantuan trees growing along salmon rivers, the salmon has delivered the lifeblood to the forest.

Of course, this is all ancient history. Wild salmon are threatened, and the techno-fixes devised by one of the most creative creatures on earth will be the salmon’s demise.

A twist to the plight of the salmon is now easily accessible to readers. In Seattle recently, David R. Montgomery, geomorphology professor at University of Washington, cast two intertwining threads of history, Europe’s and New England’s, to show how both salmon histories have been repeating themselves in Washington, Oregon and northern California for more than a hundred years. His quick-paced and humorous style helped to compress his book, King of Fish: The Thousand-year Run of Salmon (Westview Press, 2003), which is part science, part history and part folklore concerning salmon and this species’ struggles and the repeated failings of human action and inaction to “save” it.

“In coming to understand the forces shaping the rivers and mountains of the Pacific Northwest, I learned to see how the evolution and near extinction of salmon is a story of changing landscapes,” he stated.

Montgomery was one of many presenters at a conference on sustainability titled, “Building Community, Healing the Planet,” a two-day affair set squarely in the bedrock of conglomerated fields that see connections and links between human society, the environment, economics, and global ethical alliances as vastly more important in solving such problems as global warming, pollution, habitat degradation, human population explosion, inequitable economies, and over-consumption than the current Western paradigm of exponential growth in markets and technologies as solutions to growing global problems.

Montgomery, however, focused on a single topic, deadeye targeting fish and the interrelationship of three distinct human histories.

The cry of “Salmon in Danger!” is now resounding throughout the length and breadth of the land. A few years, a little more overpopulation, a few more tons of factory poisons, a few fresh poaching devices . . . and the salmon will be gone – he will be extinct.

— Charles Dickens, July 20, 1861

Interestingly, Montgomery draws from the genetic slough in a literary riptide where inventive and clearly literate writers swim: David Quammen, Barry Lopez, Richard Bass, Annie Dillard, Jim Lichatowich and David James Duncan and others have set themselves squarely inside the biotic world, allowing the rich poetry of imagery and laments drive what they write.

Montgomery’s written words dip into that same current, and his book is clearly a story of his own wonderment of geological chronology set against historical time. He gives us an overlay of the practices of migration and settling and harvesting and industrializing as well as meshing the original “old” salmon’s 40 to 20 million year evolutionary period to produce a parental species 6 million years ago that is the forebear of all modern salmon species.

Wild salmon advocates know the heuristic of the “four H’s” and each one’s relationship to the decline of salmon: Harvest (over-fishing); Habitat (mining, logging, agriculture and human land development); Hydro-dams; and Hatcheries (add to that farms/aquaculture).

Montgomery chisels a fifth H — the history of human intersection with the salmon’s evolutionary history. It’s an old story of human culture — that malleable and far-spreading diverse set of laws and actions that are passed onto other generations — T-boning right smack into the biological harmony of salmon’s persistency in nature, a consistently challenging realm of the king of fish.

His book covers the similar human patterns of change to river systems in Great Britain 300 years ago and in 19th Century New England, to those now occurring in the Pacific Northwest. The Pacific salmon (five main species) evolved under the shattered light and verdant shadows of old growth forests. They weathered and adapted to thrive under the stressors of floods, volcanic eruptions, and other major natural disturbances over millions of years. The biological trajectories of Atlantic salmon and Pacific salmon, however, have been shaped by very different conditions of topography.

Yet the Atlantic and Pacific salmon share the same fates. Of the tens of millions of Atlantic salmon returning yearly to pre-settled New England, only 1,000 wild Atlantic salmon return to this region’s rivers and streams.

Today, 90 percent of wild Pacific salmon fish runs are gone:

Pacific NW Salmon Region Current % of Wild Fish in Runs Compared to 1820

Alaska 106%

British Columbia less than 3%

Puget Sound 8%

Washington less than 2%

Columbia River less than 2%

Oregon 7%

California 5%

“I keep forgetting that the Seattle I know is brand-new, a recent addition to the landscape. Though the transformation from impenetrable forest to modern city happened in a geological instant, the dramatic changes that accumulate from daily experiences seem imperceptibly slow by human standards,” Montgomery writes. As the geologist, he seeks that long-view of the angle of repose, searching for timeline after timeline perspective for some sort of context to explain how salmon have become so imperiled.

Yet, the short view helps Montgomery appreciate human impact: “The primeval forest that blanketed Seattle for 98 percent of the last five thousand years disappeared in a little over a century.”

Early on Montgomery posits a question a reader might ask: A lot of books have been written about salmon. Why write another one?

“The fate of salmon is closely tied to changes on the land. The fall of the Pacific salmon is the direct result of both over-fishing and other actions that subsequently reshaped the landscape. The story is not simple. But the basic connections are clear.”

Throughout the book the reader explores with Montgomery the history of the “three full-scale” experiments on the salmon’s adaptability to this altered and obliterated landscape, the cause of which is human land use and unchecked development. “The strikingly similar history of salmon across these regions carries clear implications for modern salmon recovery efforts.”

Today, the blame game seems to be the biggest issue head-lined in the media concerning this story of the obscene decline of wild salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest: Some attribute the decline of salmon on Native American fishing. “The timber industry caused it,” yells the fisherman. The land developers blame the commercial fisherman. Salmon-eating sea lions and birds get scathed by some. “Everybody except dry-land farmers blames the dams.”

Without a doubt, after decades of research and field studies, and after thousands of papers and reports have been written, a general agreement within “scientific circles” makes it clear what the primary factors (those four H’s) are in the salmon’s decline.

“[A]ctions to stem known causes remain either mired in institutional, corporate, and societal denial, dissipated by spin-doctoring, or thwarted by political agendas and bureaucratic inertia.”

But it’s the history that truly makes Montgomery’s book compelling. The first H, harvest, was addressed in 1030 A.D., for example, when Scottish King Malcolm II closed the season for taking “old salmon” (spawners) at the mouth of any river on their way up to spawn.

Regarding habitat, Richard the Lion-hearted of England in the 12th century declared that rivers should be kept free of obstruction “so that a well-fed three-year-old pig could stand sideways in the stream without touching either side” (known as the King’s gap to allow adult salmon to reach spawning grounds).

Concerning hydropower, Robert the Bruce (1318) invoked a fine and sentence of forty days in prison for anyone setting up “fixtures that would prevent the progress of salmon up and down Scottish rivers.”

Montgomery isn’t writing this book to show a one-dimensional salmon advocacy or preach dam-breeching on the Columbia and Snake rivers. He sees salmon as a natural bank account, and an indicator of the entire human and natural systems’ conjoined health.

A sustainable management plan for salmon recovery means restoring habitats, writing off other habitats that are too heavily populated and developed, rehabilitating the wild salmon populations by stopping fishing for a while, restoring floodplains, and hiring and empowering riverkeepers, he professes.

“We have to plan for a hundred years, adapt how we live on and across the land to better conform to how the landscape works, and then enforce the plan and learn from history,” he told the audience.

At the close of his book, Montgomery asks whether the salmon story will end with the right Sixth H: “Will it be hubris or humility?”

Paul K. Haeder teaches college at Spokane Falls Community College and other places. He is a former daily newspaper journalist in Arizona and Texas, whose independent work has appeared in many publications. As a book reviewer for the El Paso Times, many of his reviews appeared in other Gannett newspapers.

Other Articles by Paul K. Haeder

* Flat-Earther Bush’s Style for Wild Salmon (Part I of III)

* Are We Choosing Failure? A Review of Jared Diamond’s Collapse

More:

Interview with David James Duncan by Paul Haeder

To writers at the moment I would say, yes, it’s a struggle to keep our frail art form together, but hey, it’s a damned interesting time! Humanity is in the midst of a massive transition, so human communication is undergoing a transition. A tough-minded response to your question might be something like Robinson Jeffers’ line:

“There is no reason for amazement: surely one always knew that cultures decay, and that life’s end is death.”

All human endeavor — including even our literature — is transitory. I’ve spent my life immersed in the myths, scriptures and bardic songs of the world — the best records of the best things human beings have said, sung and done for thousands of years. A little familiarity with this body of knowledge takes a lot of the stress out of living in a time of transition. The decline of literacy causes a lot of hand-wringing. But literacy is itself a recent human development — and a lamented development by the bards and singers of the oral cultures that preceded our literate one.

To learn to live with the earth on the earth’s own terms is more important to me than literacy. I lived on the Oregon Coast at a time when the most ancient Sitka spruce groves in the world were being converted daily into the L.A. Sunday Times. There was, in my view, nothing in the Times’ stories of that era that compared in beauty or import to the trees that were slaughtered to create the newspapers. The news those trees were emitting was something invisible, called oxygen. The news those trees published constantly was keeping the planet alive. We killed them in the name of literacy. — David James Duncan

Camas Culture

by Paul K. Haeder

The process of turning up earth and shaking off soil from the roots of a bulb is as old as human time. From Arctic regions to the American Southwest, from the foothills in Bhutan, to the outback in Australia, from the Amazon Basin to the Sahara, wherever humans journeyed and settled, digging into earth for the tuber, bulb, root, sustenance of Mother Earth has always brought with it the ritual of sharing with family and tribal relationships.

For the Nez Perce and other First Nations tribes throughout this area — Umatilla, Yakama, Colville, Salish, Kalapuya, Couer d’Alene — their particular digging grounds are sacred places where the camas, an onion-like bulb from the species Camassia quamash, grows in abundance and is harvested in July and August.

I was lucky enough to have been invited for a quick journey to traditional camas digging grounds last summer with Grey Owl and his wife, Martha Oatman, members of the Nez Perce Tribe. The husband and wife team instructed me on the ethno-botany of such important Nez Perce plants as bear grass, mountain tea (Labrador tea) and dog bane (Indian hemp), but more importantly they shared their tribe’s deep connection to earth skills like camas digging and its eventual cooking and storing, as well as where to find kaus-kaus (qaws qaws), a gnarly root that has such healing properties as lowering blood pressure and is used as an anti-bacterial medicine.

The gift that they afforded me, which will live in memory forever, is the deep-running narrative history of their people as they floated me back to a time of old ways, in valleys and forest 30 miles northeast from Kamiah, Idaho, following the cut banks of the Lolo Creek.

Troubled Girls Sweating

Before digging for camas and qaws-qaws, I had to journey back into my own heart by witnessing the modern world bisecting the old. I sped down from Spokane to a spot on the Clearwater River (the Nez Perce call it “little river” and name the Columbia “big river”), just west of Orofino, Idaho, anxious to meet Grey Owl, who was at a camp with fellow spiritual and Indian skills guide Grey Wolf. The two had finished a day-long series of education and healing workshops at the Clearwater River Company’s tepee rendezvous working with a group of 17- and 18-year-old girls from a youth redirection program called Spring Creek located near Thompson Falls, Mont.

The nine young women had just finished a purification in the sweat lodge, a physically healing and enlightening process most non-Indian folk never will partake in.

“I didn’t know whether I would do a sweat or not when I was hired to work with these girls,” Grey Owl told me. “It’s a matter of determining on the spot while I’m with them if certain people are going to take it seriously or not. I don’t hire out my sweat lodge, and it was a matter of gauging whether the group was right for it.

“These are white girls from ‘normal’ American middle-class families who have gotten into drugs, sex and boyfriends who have beaten them up … and in most cases whose parents have money and send them to these programs to fix them. I always say there are never bad kids, just bad parents.”

The girls had just helped build a campfire and were ready to have their cathartic and synergistic moment; Grey Owl led them through the talking circle with an eagle plume that was passed from person to person, while each feather-holder reclaimed something about herself.

The fire drew us into deep collective and individual reflection, at the very spot — probably — where, in 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their band learned from the Nez Perce how to carve out 45-foot canoes.

Each articulate young woman considered her past, her place on earth as a woman. They deeply thanked Grey Owl and Grey Wolf for their emotional and metaphysical guidance. Many broke down in tears for “the gift of knowing two men who really cared about our futures.”

Variations of the mantra, “I am pure, I am strong, I am beautiful, and I am a worthy, free, powerful woman,” ended each girl’s talking round, many of which centered on troubled pasts and new beginnings.

Then came the baptism through fire. The day before, their leaders asked each teenager to write one bad thing in her life or one negative character on a scrap of paper; the scraps then were hung on a tree. Now, each girl threw her paper into the fire, each paper holding inside a wish to change, a desire to forget.

Somewhere out in the firs and pines, a series of owl calls cut through as a moon rose above the Clearwater, in a place where the beaten-down white men of Jefferson’s dream of empire were fed steelhead and taught by the Nez Perce to build canoes to further their journey to the Pacific.

The tribe saved the Corps of Discovery, and now two modern Indians were helping guide those whom white society deems “juvenile deliquents” back to believing in their humanness and goodness.

These were my first hours before I would begin the passage back in time, back to the lore and nuances of the camas, the roots that gave sustenance to dozens of tribes — the very tubers that fed the men of Lewis and Clark.

Harvest of Bulbs

There are supposedly seven species of camas in this part of Nez Perce country, six of which are poisonous. The act of going to the grassy wetland fields when the camas plants are in bloom in May and June allows the women and girls (it was a woman’s duty in the old days to dig and prepare camas, but not so today) to pull out the bad species, including a white-flowering camas called “the death camas” because it will kill you soon after eating it, Martha Oatman told me.

The camas that the Nez Perce, Salish and other tribes use possesses a beautiful blue flower. The camas was once so prolific and abundant that in some places along the Flathead River, early white travelers mistook fields of its blue flowers for distant lakes.

For more than 10,000 years, the journey to camas fields has fulfilled many tribal nations’ connection to the earth. Archaelogists have found camas ovens that date back 4,100 years in what is now Oregon, and other such research has revealed evidence indicating that this variety of the lily plant has been part of the diet of the Native Americans in the Willamette Valley for 8,000 years.

Dried or canned camas — which first goes through a process of digging, peeling, cleaning, air-drying, and then roasting in a stone-lined pit, covered with wet bear grass, alder leaves and topped with a less intense driftwood-stoked fire for three days — is in high demand, but few contemporary members of the Nez Perce are willing to go through the physical labor of the camas way.

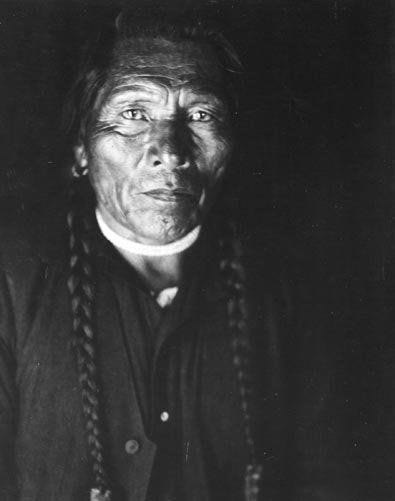

Only 100 families use the special spot, said Oatman, whose native name is Tse tal pah. She is the great-great-great granddaughter of Looking Glass, the Nez Perce brave who was in charge of warriors and was killed by the U.S. Army at the Battle of Bear Paw in Montana in 1877.

Oatman’s Nez Perce name translates to”leader.” She was named after the 15-year-old girl who was the only Nez Perce willing to face a hail of Army bullets to retrieve the rifles that the tribe had voluntarily stacked under the Army’s flag of truce.

“She just kept going back and forth and bringing rifles so the Nez Perce could regroup and hold off the Army,” Grey Owl recounted. “Few escaped that massacre, but Tse tal pah made it to Canada and she had a son who had a son who had a daughter who gave birth to Tuk luk sema — which means ‘seldom hunts’ — and that is my wife’s father, who is a fisherman.”

[Henry Looking Glass]

A Sea of Blue Flowers

Seeking camas is part of a process of fusing oneself with Nez Perce memory and narrative design. But the nitty-gritty of camas harvesting is pretty interesting on its own terms. To get large camas bulbs, the soil has to be worked yearly; the digging clears away weeds, grass and the encrouching smaller bulbs, aerating the soil and resulting in a type of artificial selection and biological cooperation from human agricultural manipulation.

By the time I met Grey Owl and Oatman, they had dug up 30 gallons of bulbs, camping along the camas field on weekends in what turned out to be a very hot, dry August.

The holes that have been excavated must be filled back in “to heal the earth” and to ensure a new season of camas crops.

While camas isn’t supposed to be sold as a commercial commodity, a small portion of dried or jarred camas can fetch more than $30. In addition to the Nez Perce, Umatilla and Yakama tribal members travel to the very spot I was taken to because of the abundance and size of camas.

We carried with us modern-day versions (metal) of the ancient digging tool tuukes — a three-foot, curved spiky fire-hardened wooden tool with a T-shaped antler handle — and canvas bags, as our duty was to sit on earth, upturned 12-inch deep clumps of soil and sod, and break apart with fingers the clods where the camas bulbs — from almond-sized to chicken egg-sized — were nestled.

Signs of digging and filled-in trenches from harvest cycles weeks earlier could be seen, evidence that the “aunties” were doing the hard labor of love that has been passed down generation after generation for thousands of years. While I was there with my hosts, another husband-and-wife team set up an umbrella and went to unearthing their harvest of camas.

Even though camas harvesting goes back as a traditional, secretive gathering amongst many families, the tribe does revel in its tranformative nature. The annual Weippe Camas Festival (held each May near Kamiah, Idaho) commemorates the role of camas in Nez Perce culture and the arrival of Lewis and Clark.

“The Camas Prairie was named because the plant was so abundant,” says tribal member Gwen Carter, who spent her juvenile years harvesting the camas in a traditional digging area. “I know my grandmother and aunts went digging as children, and I learned from my mother.” Carter, like Oatman, Grey Owl and others, wants to keep the root as part of the Nez Perce diet and to preserve the last remaining digging grounds.

The men in Lewis and Clark’s expedition 200 years ago tasted the sweet fig-like potency of dried ground-up camas; in fact, Lewis recorded extreme stomach cramps running throughout the 28-man company, probably due to raw camas dining.

“Camas is a complex carbohydrate that needs special preparing and cooking to be digestable. Severe gas and stomach pain can result if not properly prepared,” Grey Owl said when I brought this up, chuckling.

Many like Grey Owl speak of how the traditional camas digging areas enticed the Nez Perce to travel outside their 1863 reservation bounds, largely contributing to the start of the 1877 war with the United States.

When I asked Oatman how long it took the pre-modern generations of aunties to cook the camas, she states — “from three hours to three days, depending on how close the soldiers were” to the camas grounds. She and her husband hope that a tribal program that reintroduces traditional ways and thinking young folk — Students for Success — will also incorporate camas harvesting into the curriculum so young people can learn the whole process as just one of many important cultural traditions.

Roots of Medicine & Digging bring with it a time for reflection. Deer bolt out of shadows. A bull moose scours cattails near a pond. The sky, pines and cedars blend into one space where brown hawks look for muskrat and camas rat (pocket gophers). Stories then are unearthed with each riptide of earth. Every gush of sweat mixing with the tiny camas bulbs that are put back into topsoil becomes a man’s future harvest of memory.

Dig and reflect. Dig and talk.

Oatman’s humor is wry and active. For example, I learned that the common powwow dance, “Duck and Dive,” was born out of the Battle of Big Hole, Mont., when the officers of the cavalry told the soldiers to “aim chest high at Nez Perce warriors.” My camas-digging education was peppered with tribal lore, wisdom, politics and generations of narrative threading.

As part of the agreement, Grey Owl offered to take me to another spot, in a wetter forest, into the shadows, where medicinal magic springs out of the tannin and humus of Idaho’s drippy forests.

Oatman and Grey Owl led me to a place where we searched and dug for the qaws qaws that has co-evolved with neck-tall ferns in swampy, dark forests. It’s a powerful medicine used in sweats and healing. It is potent and pungent, a celery-tasting, ginger-looking mass of flesh that can cure everything from stomach problems to low energy to a lowered libido. I’ve taken my own stash back to Spokane and let it slowly cure in my basement, drying.

This quick passage into Idaho and my immersion in traditional healing will last a lifetime. I’ll be looking for the camas blooms at Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge each spring. I’ll search for the white starry blooms of the qaws qaws on my next summer hike in some western Idaho haunt.

To demonstrate the value of a food or medicinal source to a tribe, my guides told of how the Kamiah-area qaws qaws root was traded throughout Montana, Wyoming and even as far as the Dakotas hundreds of years ago, which is how the Nez Perce acquired the best Appaloosa horse stock. The Cherokee, Cheyenne, Lakota and other tribes would take a look at the Nez Perce’s big qaws qaws roots “and their eyes would pop out of their heads,” Oatman said as we wandered the forest.

Few people today look for qaws qaws or camas, she says, because it’s hard work and takes time to clean, dry and prepare.

Grey Owl beamed when he recalled the previous year’s digging of camas with a woman who was six-months pregnant, her spouse digging alongside. The pregnant woman’s goal was to dig enough camas to prepare as food for her infant during the upcoming winter.

Trials and Treaties & r & Once the reservation system was entrenched, tribes faced losing connections to ancient land and long-utilized food and medicinal preparations. Their resilience against the early U.S. government is profound, even ironic. Take Indian fry bread, for instance, which is a feature at fairs, carnivals — even at Pig Out in the Park. It was born out of the vindictive practice by white settlers and their government to force tribes to take stale, years-old, almost useless wheat that had to be pounded and ground up. Its only palatable use was for flat, deep-fried bread.

The 1855 treaty, which established the Nez Perce reservation, has been broken year after year — in fact, just recently in Kamiah, an elder and his son were arrested for “getting an elk out of season.”

Hiding stores of camas in caves and in pits has saved many a tribe. Lewis and Clark and their men were really badly off when they encountered the Nez Perce, who fed them “little river” salmon, gave them potions of qaws qaws and let them taste camas, all of which revitalized them to continue on their journey. Back then, the best young female camas digger could land the best choice of a husband.

The galvanizing force that came out of my short tutelage was to reinforce my support for sustainability and deep ecology philosophy and combine it with a simple but powerful guide voiced by the Nez Perce: “Take a little here, leave a lot there.”

“Camas, like the spring salmon runs, is all tied to a circle — a great circle that is a cycle within the culture. Everything is tied together. Please remember that when you write your story,” Grey Owl said with a goodbye hug.

The Kamiah valley is celebrated for its beautiful scenery. Named from the Kamiah Creek which enters into the Clearwater river in the eastern part of the reserve. Just where the creek enters into the river the valley is about two miles wide – mountain ranges on both sides of the river – not bare steep mountains such as you might imagine, but made up of buttes little hills each rising back off and higher than the other, until the fifth, sixth or Seventh, with its pretty fir trees, makes heaven seem but a step further up. Here and there a Canyon divides the mountain ranges, letting the snow water out in the Spring and each summer to make it annual trip down the Clearwater, Snake and Columbia to the Grand Pacific Ocean.

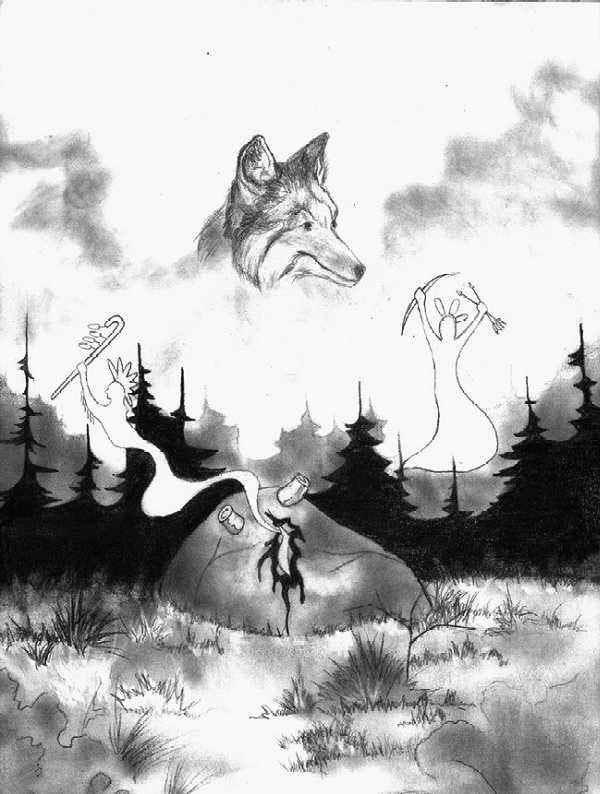

Now here in this beautiful valley down by the old ferry there is a mound so large it looks like a hill – it is surrounded by level ground. The Nez Perces call it the ‘heart’ and tell the story how it came to be there. After the world was made but not the people yet there lay a monster he was so large as to fill the great valley that mound makes just where the heart of it was. He did not need to search for food for he could draw in animals great and small for a distance of ten or fifteen miles and swallow them alive. Many a council was held (at a distance) to devise some means to destroy this enemy of all beast-kind for the valley was white with the bones of their friends. Only one among them all dared to approach the dreaded monster. This was the Coyote of little wolf for always when he drew near the creature shut his mouth saying “Go away, Go away”

One day after the Coyote had gathered some bits of pitch pine and flint, he stepped up quietly to the monster and hit the shut mouth so that if opened with a jerk. In a moment the little brave was in the great prison house and what a company he found there! Soon with his pitch and flint he kindled a fire, the smoke puffing out of mouth ears, and nose. The little commander ordered all yet alive to make their escape. white bear said he was not able to go but finally did make his exit through the ear-gate. At this time the Coyote was pawing away on the great heart with his flint, listening with delight to the sick groans of the dying monster.

When all was over and the captives at liberty there stood in the silence only the Coyote and his friend the fox. What should be done with this great body. They finally decided to cut it up in pieces and from the pieces people the world. So the Black Feet Indians were made from the feet – the Crows and Flat Heads from the head. The other tribes were made from the other parts and sent off to their own lands. The two friends were left alone. The fox looking up and down the river said Why no people are made for this lovely valley. And nothing left to make them now! True said the Coyote nothing but a few drops of the hearts best blood left on my hands. Bring me some water from the river. This was done, while the Coyote washed his hands he sprinkled the blood and water. And Lo the noble Nez Perce sprang up!