answering Mister Fish (AKA Toothless in Wisconsin) and his retort to my July Fourth screed

RE: Comments!

Well well, this is Yankee Doodle Dandy,

Yankee Doodle went to town

A-riding on a pony,

Stuck a feather in his cap

And called it macaroni.

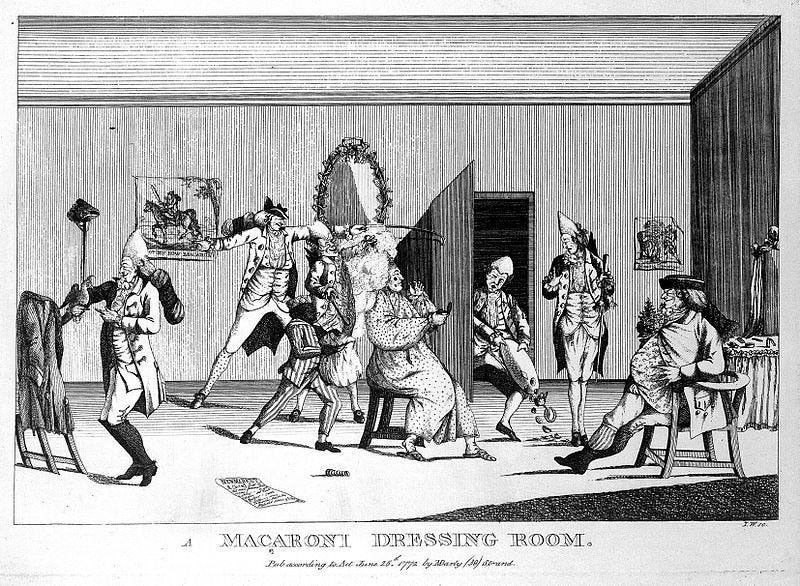

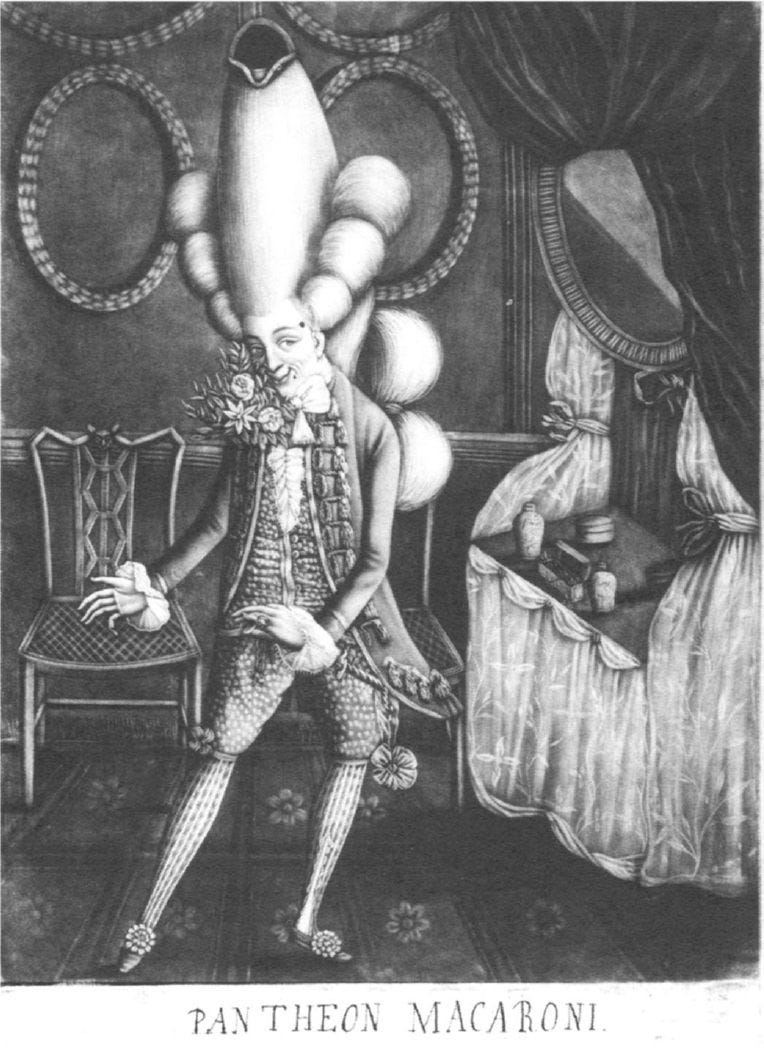

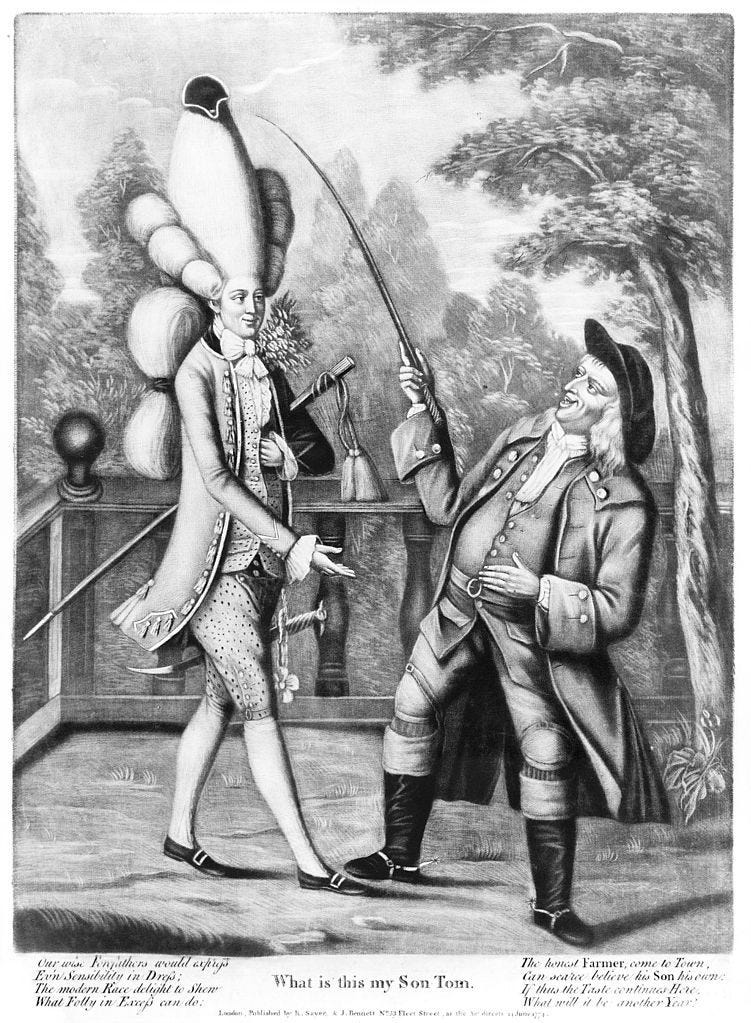

The “macaroni” in question does not, however, refer to the food, but rather to a fashion trend that began in the 1760s among aristocratic British men.

On returning from a Grand Tour (a then-standard trip across Continental Europe intended to deepen cultural knowledge), these young men brought to England a stylish sense of fashion consisting of large wigs and slim clothing as well as a penchant for the then-little-known Italian dish for which they were named. In England at large, the word “macaroni” took on a larger significance. To be “macaroni” was to be sophisticated, upper class, and worldly.

Now, if I had been a substitute teacher in some summer school, maybe the teachers would have been assigning all sorts of childish stuff, like on that National Day of Mourning (Thaksgiving) and the turkey and the white-washed faces of “pilgrims” not killing the Natives, such as the fife players and drummers marching into battle to be well meat grinder fodder.

Wimps:

Disgusting, our Anglo American roots:

It just never ends, this sickenss:

Fucking lies, and here, truth:

Fifes provided a melodic complement to the drums that provided cadence and conveyed signals to armies in the American Revolution. Like drummers, fifers were not always boys; some men spent their entire military careers playing the fife, showing the importance to the army of that skill.

Fifers were not as numerous as drummers in most armies. This means that there were fewer fifers to desert, and therefore fewer advertisements for fifers who deserted. Here are a few ads that give a sense of the diverse ages and backgrounds of fifers who served in the American Revolution.

+–+

Wilmington, New Castle County, July 11, 1775.

Run away, last evening, from the subscriber, an English servant man, named John Alderton, a Barber by trade, about 22 or 23 years of age, about 5 feet high, broad face, middling long chin, thick set, round shouldered, brown short hair, loves strong liquor, very talkative when drunk, pretends to play on the fife or beat a drum, shaves and dresses hair well, and is very cunning; he arrived at Annapolis in September last, and lived some time near that place; had on, when he went away, a jacket of such stuff as the Negroes generally wear in Maryland, an old wool hat, tow shirt, drilling or Russia sheeting drawers, white thread ribbed stockings, new strong shoes, with black buckles, and a cloth under jacket; he is remarkable for size and appearance, and it is believed that he will endeavour to pass for a free man, and offer himself to some of the militia companies for a fifer or drummer. Any person apprehending the said servant, so that his master may get him again, shall have a reward of Six Dollars, if out of this county, and if within this county Five Shillings over and above what the law allows, paid by William Brobson, Barber. [Pennsylvania Gazette, July 19, 1775]

Twenty Dollars Reward

Deserted from the New Galley, at West River, in Anne-Arundel County, on the 27th of January ult. a certain Henry Peggs, and Englishman, about 5 feet 8 inches and 3 quarters high. Had on a brown coat, black spotted velvet jacket, leather breeches, thread stockings, country made shoes, and a castor hat. He can play on the fife and drum, and has a counterfeit discharge from the galley at West River. Whoever takes up said deserter, and brings him to said galley, shall receive the above reward, from John David, Captain.

N.B. Recruiting officers are hereby forewarned from enlisting the aforesaid deserter. [Maryland Journal, February 4, 1777]

Deserted from Capt. Abraham Livingston’s Company, Col. James Livingston’s Regiment ‑ John Richards, about 5 Feet 4 Inches high, fair complexion, brown hair, tied in a club, dark eyes; had on a blue coat, faced with red, the button‑hole edged with silver, a Mason by trade, and born in Boston ‑ Also, John Davis, about 5 Feet 7 Inches high, sandy complexion, short light hair, pock‑marked, limps in his gait; had on a light brown coat, with white facings, a Native of Europe. ‑ They enlisted themselves as Drum and Fife Majors, in the Regiment late of General Patterson’s, Capt. Smith’s Company, and are supposed to be gone to Newburg.

Also, deserted from Capt. Timothy Hughes’s Company, Colonel Livingston’s Regiment ‑ Joseph Clark, about 5 Feet 2 Inches, 28 years of age, fair complexion, red curled hair, square built; had on a lightish ‑ coloured coat, a Native of Ireland. ‑ Also Nathaniel Brown, about 5 Feet 7 Inches, about 17 years old, fair complexion, light hair, a likely lad, had on a red British Soldier’s Coat, born in Connecticut. ‑ Twenty Dollars Reward will be given for each of the above Deserters, on their being sent to their Regiment, now lying at Albany, and reasonable Charges paid. Abr. Livingston, Captain [Independent Chronicle and The Universal Advertiser, February 13, 1777]

Memorandum

Kenneth McLean a Fifer belonging to the Marines serving on Board the Janus a Young lad about 4 Feet 5 Inches who deserted the night of the 19th Instant was seen in Town dress’d in Regimentals, the party who have Inlisted him, are ordered to give him up immediately. [General Orders, New York, October 21, 1781, Orderly Book July 23, 1780 – November 8, 1781, Sir Henry Clinton Papers, William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, MI]

+–+

Shifting to the dirty British, WWI:

The teenage soldiers of World War One/ 11 November 2014

As many as 250,000 boys under the age of 18 served in the British Army during World War One. Fergal Keane remembers the sacrifice they made.

War confers many things on boys who pick up a weapon to fight. They learn the true meaning of fear. They test their own capacity for courage and the limits of human endurance, physical and mental.

Some find that killing comes easily to them, too easily. And others recoil from acts of blood.

But what unites all teenage warriors is the speed with which they are hurled into a place of maiming and death.

Describing the training of a boy soldier in World War One, Wilfred Owen, wrote in Arms and the Boy:

Let the boy try along this bayonet-blade

How cold steel is, and keen with hunger of blood;

Blue with all malice, like a madman’s flash;

And thinly drawn with famishing for flesh.

Lend him to stroke these blind, blunt bullet-heads

Which long to muzzle in the hearts of lads.

Or give him cartridges of fine zinc teeth,

Sharp with the sharpness of grief and death.

From Homer’s Iliad to the present day the stories of boy soldiers evoke a particular sadness, resonant as they are of the destruction of youth and possibility.

But at the outbreak of the Great War there was nothing to suggest that the tens of thousands of boy volunteers were about to join a long, doomed procession.

Nearly 250,000 teenagers would join the call to fight. The motives varied and often overlapped – many were gripped by patriotic fervour, sought escape from grim conditions at home or wanted adventure.

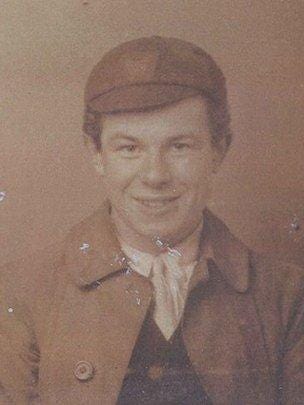

After being wounded on the battlefield it took Cyril Jose two days to crawl back to the British lines

Technically the boys had to be 19 to fight but the law did not prevent 14-year-olds and upwards from joining in droves. They responded to the Army’s desperate need for troops and recruiting sergeants were often less than scrupulous.

“It was obvious they weren’t 19,” says historian Richard Van Emden, “but you’d have a queue of men going down the road, you’re getting a bounty for every one who joins up, are you really going to argue the toss with a young lad who’s enthusiastic, who’s keen as mustard to go, who looks maybe pretty fit, pretty well. Let’s take him.”

Fifteen-year-old Cyril Jose was a tin-miner’s son from Cornwall. With the region suffering from heavy unemployment, the boy with a strong sense of adventure joined up. From his training camp he wrote an excited letter to his sister:

“Dearest Ivy, stand back. I’ve got my own rifle and bayonet. The bayonet’s about 2ft long from hilt to end of point. Must feel a bit rummy to run into one of them in a charge. Not ‘arf. Goodbye and God bless you, from your fit brother, Cyril.”

Cyril survived the war but the bloodshed he witnessed in France turned him into a vehement opponent of militarism for the rest of his life. In one letter home he poured scorn on the British commander, Field Marshal Earl Haig.

“What brains Earl Douglas must have. Made me laugh when I read his dispatch. ‘I attacked.’ Old women in England picturing Sir Doug in front of the British waves brandishing his sword at Johnny in the trenches… attack Johnny from 100 miles back. I’ll get a job like that in the next war.”

Why did so many teenagers make it to the battlefield?

Recruitment officers were paid two shillings and sixpence for each new army recruit, and would often ignore any concerns they had about age.

Many people at the start of the 20th Century didn’t have birth certificates, so it was easy to lie about how old you were.

The minimum height requirement was 5ft 3in (1.60m), with a minimum chest size of 34in (0.86m). If you met these criteria you were likely to be recruited.

Some young boys were scared of being called a coward and could not resist the pressure from society.

How did Britain let 250,000 under-age soldiers fight in WW1?

The patriotic imperative at the outbreak of war was not confined to British-born boys. For the children of migrants, rallying to the flag was proof of loyalty to their new country.

Aby Bevistein was born in Russian-occupied Poland in 1898 and came to London when he was three. In September 1914 Aby volunteered, changing his surname to the English “Harris”. Aby Bevistein’s parents were heartbroken when he joined the army. Soon after his arrival in France Aby discovered the wretched nature of trench warfare. He wrote home:

“Dear mother, I’ve been in the trenches four times and come out safe. We’re down the trenches for six days and then we get relieved for six days’ rest. Dear mother, I do not like the trenches. We’re going in again this week.”

For Aby, and many like him, the trenches meant cold and mud, wet clothes and rats, the smell of death and the sight of mutilated flesh, long monotonous hours interrupted by terror.

On 29 December 1915 Aby was caught in a German mine explosion – the enemy had tunnelled under the trench where he was stationed. He was wounded and suffered what was then simply called “shock”. In today’s military lexicon it would be described as “combat stress” or “post traumatic stress disorder”.

By early spring Aby was back on the front. On 12 Feb 1916 the Germans again attacked his position, this time with grenades.

Suffering from shock, Aby wandered back and forth along the British lines. He was eventually arrested and charged with desertion. His last letter home is that of a boy who seems determined to underplay his situation, not to put stress on his mother at home.

“Dear mother, I’m in the trenches and I was ill so I went out, and they took me to the prison and I’m in a bit of trouble now.”

The following month Aby then aged 17, became one of the 306 British soldiers executed during the Great War.

Those who survived the trenches and came home brought memories that retained the power to haunt until the end of their lives. St John Battersby was 16 when he was severely wounded at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.

Like all of the teenaged officers, Lieutenant St John Battersby had responsibilities far beyond his years, as his son, Anthony, recalls:

St John Battersby was first stationed near Serre in the Somme region

“There’s my dad, 16-years-old, really in the war. He is responsible for 30-odd men and his decisions may result in them dying or not dying. This was it.”

Three months after he was wounded, St John Battersby was back in France leading men in battle again. He could have opted to stay at home – by now the government was taking all those under 19 years of age out of the front lines. But a shortage of experienced officers meant they were allowing boys like St John Battersby to stay on if they wished.

A sense of duty compelled St John to return. Soon after coming back he was blown up by a German shell and lost his left leg. Determined to continue helping the war effort, he asked for, and was given, an administrative job in Britain.

But years later, after a fruitful life serving as a country vicar, the memories of war returned. His son Anthony remembered his father’s last hours.

“In the hour or two before he died, he was on the Western Front, yelling, ‘the Bosch are coming. We’re going over the top now’. Right down deep on the ground floor of his memory was the Western Front.”

The man facing death was once again the boy who had cheated it so many times.

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29934965

Throughout history and in many cultures, children have been extensively involved in military campaigns.

The earliest mentions of minors being involved in wars come from antiquity. It was customary for youths in the Mediterranean basin to serve as aides, charioteers and armor bearers to adult warriors. Examples of this practice can be found in the Bible, such as David’s service to King Saul, in Hittite and ancient Egyptian art, and in ancient Greek mythology (such as the story of Hercules and Hylas), philosophy and literature.[citation needed] In a practice dating back to antiquity, children were routinely taken on a campaign, together with the rest of a military man’s family, as part of the baggage.

The Roman Empire made use of youths in war, though it was understood that it was unwise and cruel to use children in war, and Plutarch implies that regulations required youths to be at least sixteen years of age.[citation needed] Despite this, several Roman legionaries were known to have enlisted children aged 14 in the Imperial Roman army, such as Quintus Postunius Solus who completed 21 years of service in Legio XX Valeria Victrix, and Caecilius Donatus who served 26 years in the Legio XX and died shortly before his honorable discharge.

In medieval Europe young boys from about twelve years of age were used as military aides (“squires”), though in theory, their role in actual combat was limited. The so-called Children’s Crusade in 1212 recruited thousands of children as untrained soldiers under the assumption that divine power would enable them to conquer the enemy, although none of the children entered combat. According to the legend, they were instead sold into slavery. While most scholars no longer believe that the Children’s Crusade consisted solely, or even mostly, of children, it nonetheless exemplifies an era in which entire families took part in a war effort.

+–+

Yankee Doodle Dandy:

On December 29, 1890, hundreds of U.S. troops surrounded a Lakota camp and opened fire, killing more than 300 Lakota women, men, and children in a violent massacre.

In December 1890, Sioux Chief Sitting Bull—who led his people during years of resistance to U.S. government policies—was killed by Indian Agency Police on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation as authorities attempted to arrest him for his involvement in the Ghost Dance movement.

In the late 19th century, the U.S. Government began forcefully relocating Native Americans onto reservations, where they were dependent on the government for food and clothing. In response, some Native American people embraced a religion called Ghost Dance, which promoted the belief that Native Americans would become bulletproof and return to their freedom following a great apocalypse. The Ghost Dance performance and religion frightened the U.S. federal government and sensationalist newspapers across the country stoked fears about an uprising by Native Americans.

Shortly after Sitting Bull’s killing, the Sioux surrendered and were marched to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. On the morning of December 29, 1890, 500 troops of the U.S. 7th Calvary Regiment surrounded a group of Lakota Sioux where they had made camp at Wounded Knee Creek. The troops entered the camp to disarm the Lakota. During a brief scuffle between a soldier and a Lakota man who refused to surrender his weapon, the rifle fired, alarming the rest of the troops. The troops began firing on the Lakota, many of whom tried to recapture weapons or flee the assault. The attack lasted for more than an hour and left more than 300 Lakota dead; over half of those killed were women, children, and elderly tribal members, and most of the dead were unarmed.

+–+

Yep, I’ve been to Vietnam and in Mexican cities, and fireworks are amazing, loud, forever rattling sometimes for hours late at night.

Many historians believe that fireworks originally were developed in the second century B.C. in ancient Liuyang, China. It is believed that the first natural “firecrackers” were bamboo stalks that when thrown in a fire, would explode with a bang because of the overheating of the hollow air pockets in the bamboo. The Chinese believed these natural “firecrackers” would ward off evil spirits.

Sometime during the period 600-900 AD, legend has it that a Chinese alchemist mixed potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal to produce a black, flaky powder – the first “gunpowder”. This powder was poured into hollowed out bamboo sticks (and later stiff paper tubes) forming the first man made fireworks.

+–+

Ah, a Chinese Tradition, this Fourth of July, as this shit-hole country wants war war war with China. It is all a lost culture, a lazy culture, immediate gratification, smoke screens, with all the smoke from fireworks. What are those crocodile tears at football games, wrestling matches, everywhere we go, for what?

Boys and girls, destroyed by war, and future boys and girls, damaged by war, and this USA is itching for a New Jerusalem in UkroNaziLandia. There will be tears this July 4th, since this country is sliding sliding sliding down down down. All for naught. Or for something, but not Jefferson.

Well, he’s wrong about Native Cultures, but those are his times, his hubris:

“Societies exist under three forms sufficiently distinguishable. 1. Without government, as among our Indians. 2. Under governments wherein the will of every one has a just influence, as is the case in England in a slight degree, and in our states in a great one. 3. Under governments of force: as is the case in all other monarchies and in most of the other republics. To have an idea of the curse of existence under these last, they must be seen. It is a government of wolves over sheep. It is a problem, not clear in my mind, that the 1st. condition is not the best. But I believe it to be inconsistent with any great degree of population. The second state has a great deal of good in it. The mass of mankind under that enjoys a precious degree of liberty and happiness. It has it’s evils too: the principal of which is the turbulence to which it is subject. But weigh this against the oppressions of monarchy, and it becomes nothing. Malo periculosam, libertatem quam quietam servitutem. Even this evil is productive of good. It prevents the degeneracy of government, and nourishes a general attention to the public affairs. I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical. Unsuccesful rebellions indeed generally establish the incroachments on the rights of the people which have produced them. An observation of this truth should render honest republican governors so mild in their punishment of rebellions, as not to discourage them too much. It is a medecine necessary for the sound health of government.”

— Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, January 30, 1787

Oh, Tommy:

“The care of human life and happiness, and not their destruction, is the first and only object of good government.”

“A wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”

“Educate and inform the whole mass of the people… They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty.”

“The constitutions of most of our States assert that all power is inherent in the people; that… it is their right and duty to be at all times armed.”

“I never considered a difference of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy, as cause for withdrawing from a friend.”

“To compel a man to furnish funds for the propagation of ideas he disbelieves and abhors is sinful and tyrannical.”

“I predict future happiness for Americans, if they can prevent the government from wasting the labors of the people under the pretense of taking care of them.”

“The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”