famous last words: the costs upfront are profits next for the titans of tyrants, and the externalities will titrate deep into your soul, into your unborn generations’ souls

You know parasitic capitalism is the cancer on the world — when the dirty thugs and polluters poison our schools, man?

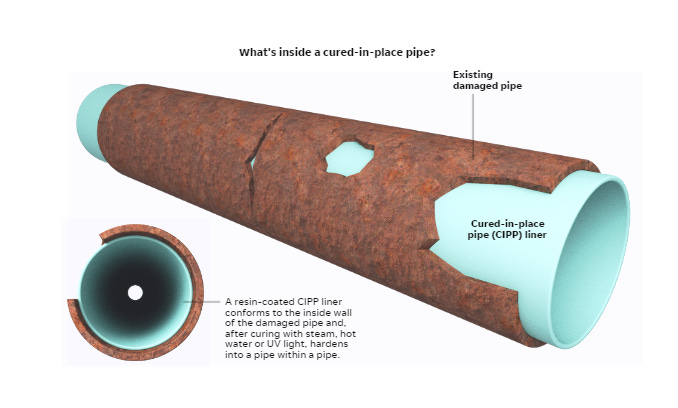

Cured-in-place pipe lining creates a new pipe inside an old one by inserting a soft, resin-soaked liner into the existing structure, inflating it with pressurized air, then heating it so it hardens. Because it’s faster and less expensive than traditional pipe rehabilitation, cities across the country are turning to cured-in-place contractors to upgrade their old underground lines.

But those cost savings can come at a price.

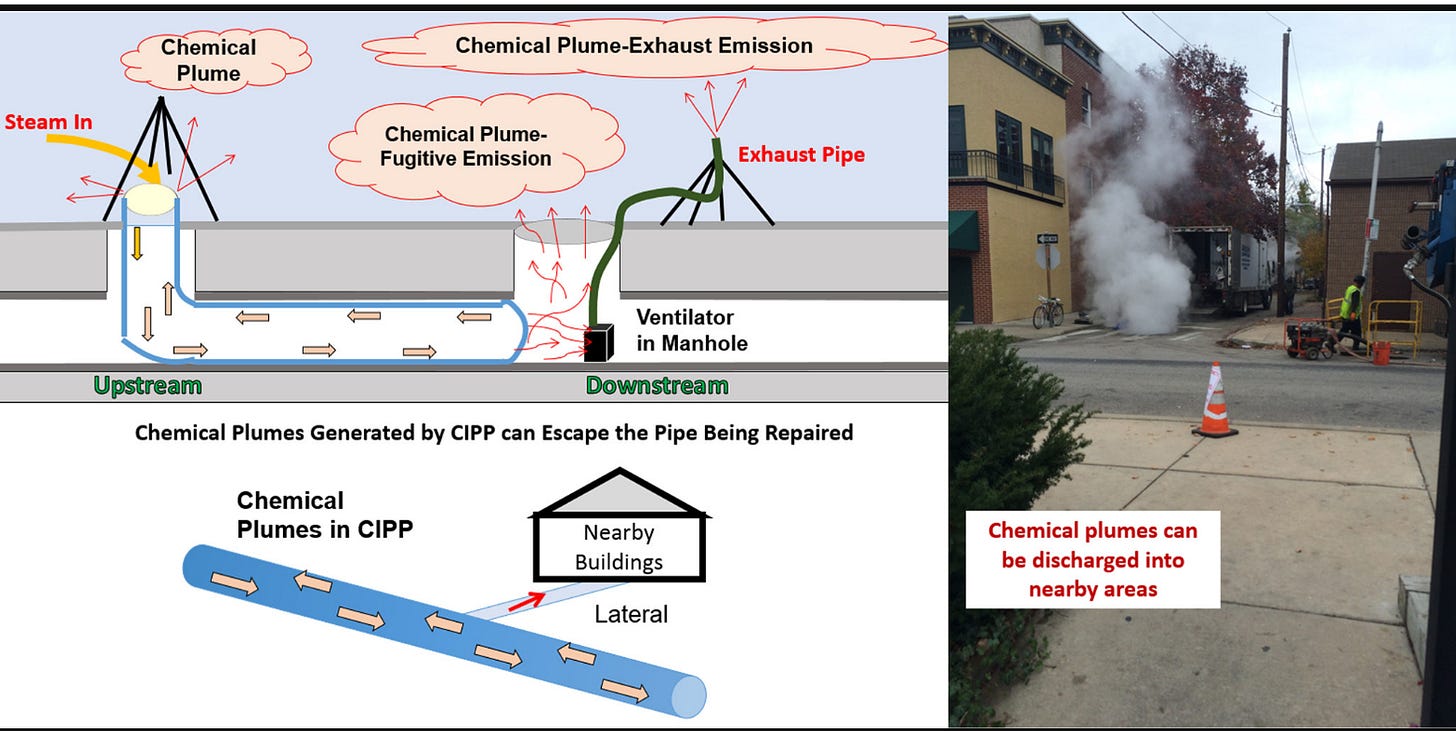

Hazardous air pollutants released during the heating process can enter homes, schools and other buildings and sicken the people inside.

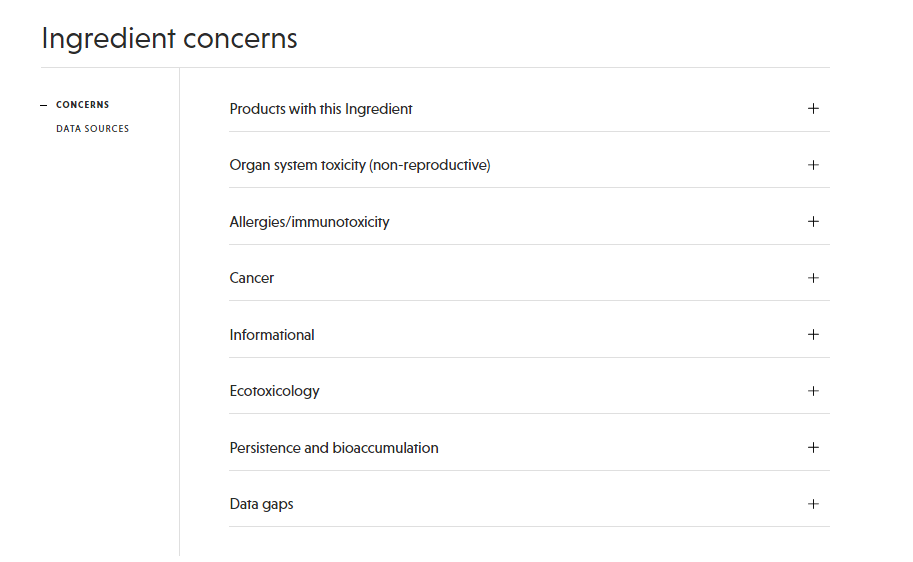

Styrene, a probable carcinogen and key ingredient in many cured-in-place projects, can be especially toxic and causes a constellation of symptoms like those reported at Merrimack Valley High School – headaches, nausea, vomiting, loss of balance and, sometimes, unconsciousness.

Similar exposures across the country have landed people in the hospital, required building evacuations and sparked claims of lasting injuries and even death, USA TODAY found.

Sarena Quintanilla, whose daughter attends Merrimack Valley High School, said the teen suffered severe congestion with a burning in her sinuses and throat after the incident. Even now, weeks later, Quintanilla said, her daughter continues to experience headaches that she believes stemmed from exposure to the fumes. (source)

Read the USA Today article. READ it. You will never ever get people quoted in it who say this is unfettered toxic capitalism on parade, and that these techno-chemical “fixes” are at a cost TOO high for a society.

No discussion in the article about how we have gutted infrastructure writ large because we are a casino capitalism system of revolving doors and captured agencies, and that the only solution is to flip the fucking script and end this predatory privatization of everything system of grand theft everything; to stop the degregulation, to end the Poison Ivy League creeps steering this country into a black hole of emptiness.

A D-minus from civil engineers? This is it for USA Today? Never ever will the inverted crappy pyramid of junk journalism talk about how zero tolerance should be the rule, that is, precautionary principle and do no harm, and that we just need to send home the bloody merchants of death in 800 proxy warring bases, and get this country to BUILD something, to WORK on the flagging communities, our crumbling sea walls, the collapsing highway bridges, the urban-rural-wildland interfacing where hundreds of millions of dollars “worth” of homes and infrastructure are at risk for wildland fires.

The entire plastics and polymers industry is dirty, cancerous, a system of deaths by 10,000 genetic (genotoxic) and endrocrine CUTS:

Cured-in-place-pipe (CIPP) is the most popular water pipe repair method used in the U.S. for sanitary sewer, storm sewer, and is increasingly being used for drinking water pipe repairs. Today, approximately 50% of all damaged pipes are being repaired using CIPP technology. The CIPP procedure involves the chemical manufacture of a new plastic pipe called a CIPP inside a damaged water pipe. Before CIPP installation, workers precut and lay-up the felt and fiberglass liner and saturate it with a polyester, vinyl ester, or epoxy resin. The resin is sometimes mixed by hand or using an automated mechanical mixer, manually poured or drawn into the precut liner. Liners are then passed through rollers to ensure that the fibers are saturated with resin. The resin impregnated liner (referred to as an uncured resin tube) is typically refrigerated until use, as it may contain volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds (VOCs, SVOCs) and thermally sensitive chemicals. This uncured resin tube is often pulled through the damaged water pipe or inserted into the damaged water pipe and inflated using forced air or water. During the installation process, the curing is facilitated by periodically forcing steam into one end of the resin tube, recirculating hot water, and/or passing an ultraviolet (UV) light train through the tube. Plastic coatings are sometimes included inside and outside of the uncured resin tube for a variety of reasons. Once the facilitated curing process has ended, the hardened ends of the CIPP are cut and removed. Connections to pipe laterals are reinstated by cutting holes into the pipe walls. A reported advantage of this in-situ repair process is the avoidance of roadway shutdowns and open-trench excavations to remove the damaged pipe. The CIPP process is also being used to repair pipes in buildings.

Little is known about CIPP worker exposures and health risks. CIPP manufacturing sites are highly transient, with a single installation location being used from a few hours to a few days. Unlike traditional manufacturing operations, there is not a ‘permanent address’ to visit or inspect. Once the construction process is complete, the workers and equipment move on. The CIPP manufacturing process can expose workers to raw chemicals, forced air, steam, hot water, ultraviolet (UV) light, materials created and released into the air during manufacture, as well as liquids and solids generated by the process and worker activities. To date, CIPP air monitoring studies have been unable to comprehensively characterize occupational exposures because of a narrow focus on VOC vapors and the use of nonspecific detectors. See below for information on the October 5th free webinar “Public Health Implications and Occupational Exposures during Water Pipe Repair Activities” (to view webinar, click here ). (source)

Go to any number of sources to see this system of polystyrene here: EWG

Those cost savings — read, massive billionaire, millionaire and Eichmann profits — kill kill kill, and the lies and the propaganda and the agency capture and the Mafia that is the trucking-oil-highway construction are killing us softly and hard.

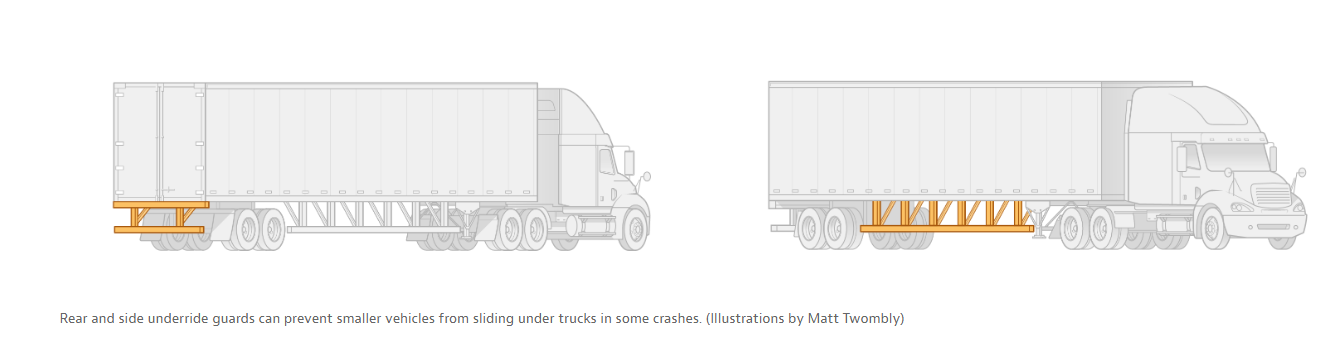

The records reveal a remarkable and disturbing hidden history, a case study of government inaction in the face of an obvious threat to public wellbeing. Year after year, federal officials at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the country’s primary roadway safety agency, ignored credible scientific research and failed to take simple steps to limit the hazards of underride crashes.

NHTSA officials failed to act, in part, because they didn’t know how many people were killed in the crashes. Their poor efforts at collecting data over the years left them unable to determine the scale of the problem. This spring the agency publicly acknowledged that it has failed to accurately count underride collisions for decades.

According to NHTSA’s latest figures, more than 400 people died in underride crashes in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available. But experts say the true number of deaths is likely higher.

Again, styrene gassing of students, or these death machines, trucks, sometimes three unit trucks, kill kill kill. The logical is thrown out with the baby’s bathwater.

David Friedman was a top official at NHTSA during the Obama years. “NHTSA has been trying, for decades, to do something about underride deaths. And yet over and over, they haven’t made the progress that we need. Why? Well, I think part of it is because industry just keeps pushing back and undermining their efforts,” said Friedman, who served as the agency’s acting administrator in 2014. “There are so many hurdles put in the way of NHTSA staff when it comes to putting a rule on the books that could address issues like underride.”

The technology at issue — strong steel guards mounted to the back and sides of trucks — is simple and “relatively inexpensive,” Friedman argued. “The costs are small.” (source)

Simple solution, almost fourth grade level stuff (though putting fourth and six graders in a large conference room with teach-ins and fuzzy problem and solution events, and, man, most solutions to this sick country’s problems would be solved, and be warned: it would be really strong left socialism, as in . . . )

“We have to tell those people they can’t do that or make that or develop that anymore without a huge screening and vetting process. Why are they killing us and our futures?”

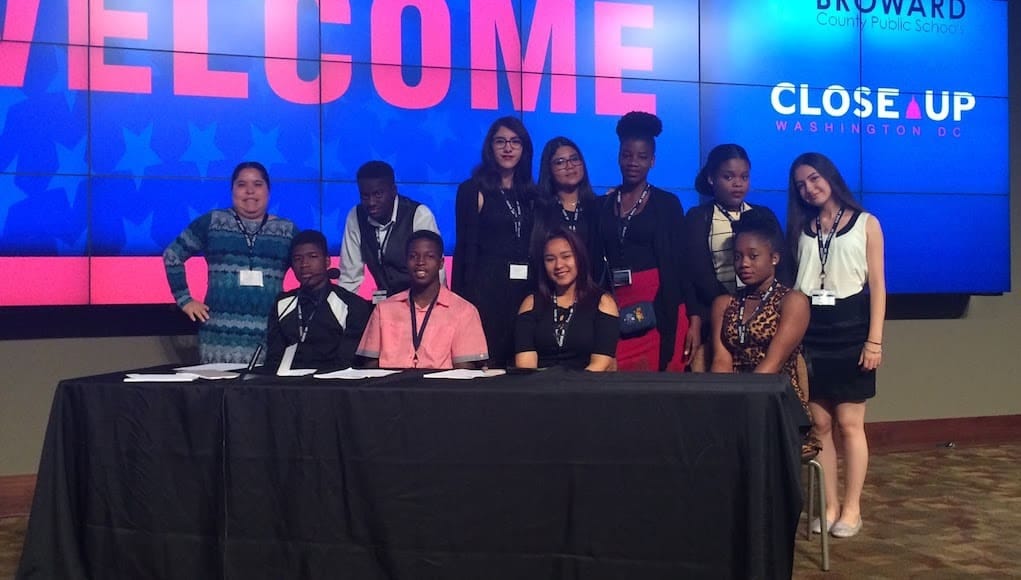

Let the youth take the helm: Project Based Learning turning into Community Based Learning and then turned into Legislative-Connected Project Based Learning: 7 Real-World Issues That Can Allow Students To Tackle Big Challenges.

Again, take over the high schools, the elementary schools. Fill the parking lots with teepees and hands-on teach-in stations. Get the youth to cook their food, and get the youth working with amazing facilitators to get into a fuzzy problem solutionary situation. Call it a global or local or regional problem solving charrette. Get the stupid policy makers, the chamber of commerces, and the big wigws in business to show up and, no, not dominate or even castigate.

Come up with a list of major problems the youth are seeing they WILL face the next 60 years — local, family, educational, county-wide, state-wide, country-wide and globally.

A weekend of rice, beans, corn, pancakes, tortillas, a global simple menu, and then, let the kids go. Every month, after the first weekend’s top 20 problems are set and discussed, a new teach-in and solutions based camp-in for each problem . . . . Get this on cable, on TV, uploaded, streamed, what have you. It will fucking work.

1) Climate Change – Climate Change will have a significant impact on our students’ lives. Indeed, there may not be one issue that will impact them more comprehensively. Students have seen the data and witnessed the changes, and are listening to the science community. They know that this an urgent issue that will affect almost everything, including, but not limited to, weather, sea levels, food security, water quality, air quality, sustainability and much more. Many organizations – such as NASA, The National Park Service, National Center for Science Education, National Oceanic Atmospheric Association and SOCAN to name a few – are working to bring climate change curriculum and projects to teachers and students.

2) Health Care – Since this has become a prominent topic in the national debate, students are becoming aware of the issues in our country related to rising costs, access, quality and equity. They are beginning to understand the importance both individually and societally. Like the aforementioned topic of climate change, students are also (and unfortunately) learning that we are not necessarily leading the world in this area. They know that this problem is connected to profits, insurance, bureaucracy and more, but they also have a fresher sense of how it could be different, and how we could learn from others around the world. The work on this topic, like many others, is being led by our universities. Institutions such as University of Michigan, Johns Hopkins and Stanford are leading the way.

3) Food Insecurity – as our students become more aware of their surrounding communities, as well as the peers they interact with daily, they begin to see differences. Differences in socioeconomic status, opportunities for growth, housing, security, support services and more. And since 13 million young people live in food-insecure homes, almost all of our students, as well as educators, know someone who is hungry on a daily basis. This may often start with service-based projects, but can also lead to high quality project based learning complete with research, data analysis, diverse solutions and ultimately a variety of calls to action. If you want to see how one teacher and his students transformed not only their school, but entire community related to food insecurity, check out Power Of A Plant author Stephen Ritz and the Green Bronx Machine.

4) Violence – This is a natural given current events taking the nation by storm. However, the related topics and issues here are not new. And yes, they are politically charged, but young people care about these issues. They care about their collective safety and futures, but also know something can be done. In addition to the specifics related to school violence and safety, students can study details of how to advocate, organize, campaign and solicit support, learn that this is a complex problem that has many plausible causes, and, perhaps most importantly, hope for progress. They also know that although they are concerned about attending school in safe environments, our society and culture have violence-related problems and issues that they want to see addressed. Following the recent incident in Florida and the subsequent response from students, the New York Times has compiled a list of resources for educators on this topic.

5) Homelessness – We often hear the expression “think globally, act locally.” The topic of homelessness has garnered more attention than ever as more and more communities wrestle with a growing homeless population. In addition to opportunities for our students and schools to partner with local non-profit organizations dealing with homelessness, this topic, like others, is also a great way to elicit empathy in our students. We often hear from educators, employers and others that we want to raise adults that are able to solve problems, improve our communities, and have the ability to see beyond themselves. This topic can provide a number of options for helping students develop those skills. Finally, we also have a growing population of homeless students. So, the relevancy and urgency are all there. Many have laid the groundwork for us to address this within our curriculum. Organizations like Bridge Communities, National Coalition For The Homeless, Homeless Hub and Learning To Give are some of the many leading the way.

6) Sustainability – This is an extremely global issue that affects everything from energy, to food, to resources, economics, health, wellness and more. Students are becoming more and more aware that our very future as a species depends on how we address sustainability challenges. They are aware that this challenge requires new ways of thinking, new priorities, new standards and new ways of doing things. Sustainability is all about future innovation. Students have tremendous opportunities to collaborate, think critically, communicate, and be creative when questioning if a current practice, method, resource or even industry is sustainable without dramatic change and shifts. Students who tackle these challenges will be our leaders – business, political and cultural – of the future. Educators and students can find almost infinite resources and partners. A few of these are Green Education Foundation, Green Schools Initiative, Strategic Energy Innovations, Facing the Future and Teach For America.

7) Education – It seems that each and every day, more and more of us (though maybe still not enough) are moving closer to realizing that our educational systems are seemingly unprepared to make the big shifts needed to truly address the learning needs of 21st-century students. The related challenges are many – new literacies, skills, economic demands, brain research, technology, outcomes and methodologies. It’s a good thing that more and more people – both inside and outside of education – are both demanding and implementing change. However, one of the continued ironies within education is that we (and I recognize that this is a generalization) rarely ask the primary customer (students) what they think their education should look, feel and sound like. We have traditionally underestimated their ability to articulate what they need and what would benefit them for their individual and collective futures. One of the many foundational advantages of project based learning is that we consult and consider the student in project design and implementation. Student “voice & choice” creates opportunities for students to have input on and make decisions regarding everything from the final product, to focus area within a topic or challenge, and even whom they may partner with from peers to professionals. It’s this choice that not only helps elicit engagement and ownership of learning, but offers opportunities for students to enhance all of the skills that we want in our ideal graduates. As one might guess, there is not a lot of formal curriculum being developed for teachers to lead students through the issue of education reform. This may need to be an organic thing that happens class by class and school by school. It can start as easily as one teacher asking students about what they want out of their education. Some other entry points are The Buck Institute for Education, Edutopia’s Five Ways To Give Your Students More Voice & Choice, Barbara Bray’s Rethinking Learning and reDesign.

This is not intended to be an exhaustive or comprehensive list. However, these seven broad topics present hundreds of relevant challenges that our students can and should have opportunities to address. If they do, they will not only be more prepared for their futures, but also poised to positively impact all of our futures.

That above list doesn’t have the fuzzy problem statement: “Can we come up with a better, more human, more resilient, more human and earth centered system to help the world thrive and undergo the massive changes reeling us with a world without ICE?” But it should!

Throw out a two dozen issues to a hundred high schools, and work work work on those, and then in those respective states, hit the county and city councils and head up to the state capitals. REALLY.

How easy is it to fix our broken windows and pipes and dirty drinking water problems. How easy is it to fix those extreme highway deaths, these underride accidents and other accidents.

If this isn’t sick,

Then is this?

Solution? Give those students a decent weekend charrette, and throw in all sorts of options and alternatives, and of course, those kids will want to be conservative in their approach: “Why so many flammable trucks are on the road . . . why are they, the government leaders and agencies, giving them, the owners, capitalists, everything and we don’t get anything?”

Just throw this out, and see what youth do with this criminal problem:

Another impetus for fraud stems from the blank checks that the Pentagon writes to contractors. The most common method of winning contracts is through the “cost-plus” contracting system, in which the government reimburses contractor expenses and tacks on a commission as profit. According to Hartung, the system works in such a way that “the more work [contractors] do, the more profit they get, even if their work is inefficient. … It basically says, ‘If you spend a billion dollars building a weapons system, you’ll get a 10 percent profit or $100 million.’” Essentially, for contractors, “you do better if you are wasteful.”

Yes yes, these students need REAL world thinkers, and no, solving the world’s problems should not be funneled into STEM ONLY— science technology engineering and math. The world is run by minds, perception, politics, community engagement, rhetoric, research, writing, debate, history, geography, and so much more OUTSIDE the real of computing, bridge building, mRNA bioweapons, algorithms.

As the late Gore Vidal pointed out in his book, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated, the United States always appears to find a new enemy to attack to perpetuate controlled wars, or small conflicts that keep dollars flowing to sustain the defense industry. William Hartung, the Center for International Policy’s Arms and Security Project Director, stated that there is an “excess of usable military equipment relative to any possible need.” As Hartung put it, the overriding sentiment in the government has been that “we need [the money] to defend the country, so we can’t ask too many questions.” When there are calls to cut the defense budget, to withdraw and stop intervening in world conflicts, or to use older equipment available, contractors and lobbyists respond by arguing that the country “needs a new generation of equipment,” or that the Pentagon needs to continue a steady stream of purchasing in order “sustain the defense industrial base” to prepare for the next war. (source)

That Gore Vidal: “He’s denounced Washington for waging what he called “a perpetual war for perpetual peace” and said American aggression was only nurturing fresh hatreds.

In a scathing attack on U.S. foreign policy, Vidal told Reuters that the United States would have been better served trying to buy peace with Osama bin Laden rather than send in the bombers to try and kill him.

Vidal, one of contemporary America’s harshest critics, has had trouble finding an audience for his views back home and is publishing his latest collection of essays in his adoptive country, Italy.”

And so, cancelled and thrown into the dustbin of distraction and dumbdowning. Oh, that sacred shitting, burping, farting, urinating cow: “US Military Pollution: The World’s Biggest Climate Change Enabler”

Hmm, what would those fifth, eighth eleneth graders say? In AmeriKKKa now, there is hardly any critical thinking in K12, and the demands on teachers are out the window, and the parents are checked out, and their kiddos are one learning disability and allergy and chronic illness away from disability!

Thanks for this, Paul. Do you know good articles that emphasize how money corrupts our whole legal system? How unimportant the people have become, their needs and well-being supposedly the object of any work being done, of any kind? The object has become merely making money, the more the better. It seems that few understand the level of corruption to which capitalism has developed. It seems like the topic needs to be discussed at that level, so that individual manifestations of it can be linked to the same source.

Maria I move on July 27 and 28. Already packing what I don’t use on a daily basis.

LikeLike

Man, Maria, time for me flies and stagnates, and your move to Portland is coming up. The place is almost finished, I assume, and this move is going to be a big one for you.

So, I must see you here soon while you are still on the coast. I’ll drop you an email today and see which day or days work out best for you.

Now, now, the articles? About how the entire regulatory agencies have been captured by lobbies, industry groups and are run by corporate heads? The very fact administrations are stacked with people coming from Wall Street, K-Street, Fortune 5000 companies says it all, no, the revolving door that puts people way past second fiddle in the dirty boys and girls in the band.

There’s a newish book by the French economist. Here, an interview, from the Harvard rag:

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/03/pikettys-new-book-explores-how-economic-inequality-is-perpetuated/

Q&A with Thomas Piketty

GAZETTE: You write that inequality is not the result of economics or technological change, but is rooted in ideology and politics. How so and why is it important to understand its roots — how does that aid in its dismantling?

PIKETTY: What I do in this book is take a very long-run look at the inequality regime in a comparative perspective. I define “inequality regime” as the justification [used] for the structure of inequality and also the institutions — the legal system, the educational system, the fiscal system — that help sustain a certain level of equality or inequality in a given society. I look at the history of this inequality regime over a very long run, across many countries and regions of the world, and what I first observed is a lot of variation over time. You see very fast transformation, sometimes due to revolution, [like] the French Revolution. But also, Sweden used to be a very unequal country until the beginning of the 20th century. And then, following a very large social mobilization by trade unions and the Social Democratic party, Sweden became one of the most equal countries in history. You could say the U.S., after the Great Depression, also turned to a very progressive tax system and reduced its inequality enormously.

And so, in all these historical experiences, what’s very striking is the speed and the magnitude. If you had told people in Sweden in 1910 that the country was going to become a social democratic Sweden 20 years later, nobody would have believed it. The dominant groups always tend to be conservative and always tend to define the existing inequality as being natural, coming from some natural scheme or natural institutions or from rules that cannot be changed. But, in practice, what you see is something very different: The way inequality is organized can change very quickly. Sometimes it takes major shocks, including revolution and war, but it also happens very often in a peaceful manner like Sweden or the U.S.

So this is the story I tell in the book, and it’s important because I think it will be the same in the future. Nobody knows where change will come from — from an election, from social movement, the growing awareness of the climate crisis or other factors of change. But the idea that the current economic system will never change and we’ll just continue with business as usual forever is just not convincing at all, especially in light of the rich political history of inequality regimes that I put forward in this book.

“It’s everybody’s job and responsibility to take part in this conversation about changing the economic system.”

GAZETTE: You seem to have taken to heart some of the limitations of “Capital in the 21st Century.” One that you’ve frequently acknowledged is the last book’s Western-centric focus and what you’ve called its “black box” treatment of the political and ideological changes associated with inequality. How have you tried to rectify those shortcomings here?

PIKETTY: First, I show how the rise of inequality in Western societies was very much rooted in a system of world domination and of colonial domination and colonial appropriation. It’s a theme that was present a little bit, but was not very well developed. So now, I insist on the importance of slave societies and post-slavery colonial societies in the formation of modern inequality. It played a very big role, and in particular, the large wealth portfolio of European society in the 19th century and early 20th century came from colonial wealth and colonial appropriation. It also played a big role in this [private] ownership society in the 20th century. The international dimension and the colonial dimension of the inequality regime of the 19th century and early 20th century is very important in order to better understand the origin of the transformation that finally took place in the 20th century.

Also, the system of justification of inequality is also much more at the center of this book. The last part of this book is tied to the evolution of the electoral structure — who votes for the Democratic Party in the U.S., who votes for the Labour Party in Britain or for the Social Democratic Party in Germany or the Socialist Party in France. All of this changes [after] World War II. I show that these parties that were the parties of workers and had the highest electoral score among the lowest education group and the lowest income and wealth group, have actually become, over the past 40 or 50 years, the parties of the educated. I try to understand why and argue that this has to do with the ideology of these parties. The political platforms advocated by these parties have become less and less concerned with inequality and redistribution, or at least this is what I argue. This work is able to better go after the matter when it comes to the deep forces behind changes in inequality.

Chart showing the share of the top decile (the 10 percent of highest earners) in total national income ranged from 26 to 34 percent in different parts of the world and from 34 to 56 percent in 2018.

The share of the top decile (the 10 percent of highest earners) in total national income ranged from 26 to 34 percent in different parts of the world and from 34 to 56 percent in 2018. Inequality increased everywhere, but the size of the increase varied sharply from country to country, at all levels of development. For example, it was greater in the United States than in Europe (enlarged European Union, 540 millions inhabitants) and greater in India than in China.

Sources and series: see piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.et

GAZETTE: Much of current focus on inequality centers on the rise of right-wing populism and appeals to ethnic, religious, and national divisions. But you say the rise of elitism and the left’s failure to offer a persuasive counter-ideology to right-wing populism deserves more scrutiny. Can you elaborate?

PIKETTY: What I mean is that in the post-War period, in the ’50s and ’60s, the Democratic Party in the U.S. and social democratic parties in Europe were able to convince voters with lower education, lower income, lower wage[s] that they are the platform for them. That, in effect, what ties them together, despite their differences … is a platform of educational expansion, workers’ rights, Social Security, progressive taxation. [This] is what has made this coalition stick together. Then, what we see is that gradually over the past four decades, these parties have become the party of the educational elite. So while the right-wing parties and the center-right party are still the parties of the business elite or the high wealth elite … [W]e have moved from this class-based system to what I describe as a multi-elite system, where basically the educational elite votes for the Brahmin left and the wealthy elite votes for the merchant right or the business right. This rise of elitism, in effect, has left a lot of voters feeling abandoned [by] the main two parties, and I feel this has largely contributed to the rise of what is sometimes known as populism.

In 2018, the share of the top decile (the highest 10 percent of earners) in national income was 34 percent in Europe, 41 percent in China, 46 percent in Russia, 48 percent in the United States, 54 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 55 percent in India, 56 percent in Brazil, and 64 percent in the Middle East.

In 2018, the share of the top decile (the highest 10 percent of earners) in national income was 34 percent in Europe, 41 percent in China, 46 percent in Russia, 48 percent in the United States, 54 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 55 percent in India, 56 percent in Brazil, and 64 percent in the Middle East.

Sources and series: see piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology

GAZETTE: You propose a way forward that reinstitutes a progressive tax system that will fund something like a universal basic income. Broadly, what does that look like? How do you get the rich and powerful to give things up? And why was it important to you not just to document and analyze inequality, but to also offer a possible solution?

PIKETTY: It’s everybody’s job and responsibility to take part in this conversation about changing the economic system. I think it’s too easy for scholars and social scientists and economists and historians like myself … just to describe or to talk about history and not to take a stand in the present and in the future. So I’m trying to make an effort to deal with the future. People can either believe or come to their own conclusions from the historical material I present.

What do I feel has the most promise for the future? There are two main ideas, one is social federalism and the other is participatory socialism. Social federalism is a view that if you want to keep globalization going and you want to avoid this retreat to nationalism and the frontier of the nation-state that we see in a number of countries, you need to organize globalization in a more social way. If you want to have international treaties between European countries and Canada and the U.S. and Latin America and Africa, these treaties cannot simply be about free trade and free capital flow. They need to set some target in terms of equitable growth and equitable development. So, how much you want to tax large international corporations [and] high wealth/high income individuals? What kind of target do you want for carbon emissions? Free trade and free capital flows can be part of this new and more social international treaty that we need to organize globalization, but they can’t be the first chapter of this treaty. They must be put to the service of higher goals, goals about sustainable development and equitable development, and they must be regulated. Technically, it’s not so complicated. The issue is really not political and ideological. We’ve been accustomed for several decades to treaties without any explicit fiscal or social policy. This has to change.

Participatory socialism is the general objective of more “access” to education. Educational justice is very important in terms of access to higher education. Today there’s a lot of hyper criticism, not only in the U.S., but also in France and in Europe, that we don’t set quantifiable and verifiable targets in terms of how children [from] lower [income] groups [gain] access to higher education, what kind of funding [they] have for higher education. The other big dimension is circulation of property, so I talk about “inheritance for all.” The idea is to use a progressive tax on wealth in order to finance [a] capital transfer to every young adult at the age of 25. This transfer is in effect, 120,000 euros [about $134,000] per person, [which is] about the level of medium wealth today in France or in the U.S. That will very much transform the ability of children from poor families or middle-class families to create their own firms. Just having this kind of property puts you in a different position in life in general — what kind of jobs, what kind of wage, do I need to accept? It transforms the basic structure of power in society and that’s something very important. What I propose is not full equality; there will still be a lot of inequality. But this would make a big difference. The general idea is that not only the children of wealthy parents who have good ideas can create companies and participate in the economy. We need to rely on a much broader group of the population.

Or, here:

BUT. I’ll take David any day, may he Rest in Peace:

Professor David Graeber (LSE) speaking at the University of Birmingham as part of the Birmingham Research Institute of History and Cultures’ interdisciplinary conference ‘Debt: 5000 years and counting’.

David Graeber (1961 – 2020) was an American anthropologist and anarchist activist. His influential work in economic anthropology, particularly his books Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011) and Bullshit Jobs (2018), and his leading role in the Occupy movement, earned him recognition as one of the foremost anthropologists and left-wing thinkers of his time.

He talked about culture:

https://www.artforum.com/print/201206/michelle-kuo-talks-with-david-graeber-31099

Chomsky (not someone I revere) interviewed here about David’s posthumous book:

https://artreview.com/noam-chomsky-on-david-graebers-pirate-enlightenment/

Here, the Guardian, interesting:

David Graeber interview: ‘So many people spend their working lives doing jobs they think are unnecessary’

Stuart Jeffries

The anarchist author, coiner of the phrase ‘We are the 99%’, talks to Stuart Jeffries about ‘bullshit jobs’, our rule-bound lives and the importance of play

A few years ago David Graeber’s mother had a series of strokes. Social workers advised him that, in order to pay for the home care she needed, he should apply for Medicaid, the US government health insurance programme for people on low incomes. So he did, only to be sucked into a vortex of form filling and humiliation familiar to anyone who’s ever been embroiled in bureaucratic procedures.

At one point, the application was held up because someone at the Department of Motor Vehicles had put down his given name as “Daid”; at another, because someone at Verizon had spelled his surname “Grueber”. Graeber made matters worse by printing his name on the line clearly marked “signature” on one of the forms. Steeped in Kafka, Catch-22 and David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King, Graeber was alive to all the hellish ironies of the situation but that didn’t make it any easier to bear. “We spend so much of our time filling in forms,” he says. “The average American waits six months of her life waiting for the lights to change. If so, how many years of our life do we spend doing paperwork?”

The matter became academic, because Graeber’s mother died before she got Medicaid. But the form-filling ordeal stayed with him. “Having spent much of my life leading a fairly bohemian existence, comparatively insulated from this sort of thing, I found myself asking: is this what ordinary life, for most people, is really like?” writes the 53-year-old professor of anthropology in his new book The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. “Running around feeling like an idiot all day? Being somehow put in a position where one actually does end up acting like an idiot?”

“I like to think I’m actually a smart person. Most people seem to agree with that,” Graeber says, in a restaurant near his London School of Economics office. “OK, I was emotionally distraught, but I was doing things that were really dumb. How did I not notice that the signature was on the wrong line? There’s something about being in that bureaucratic situation that encourages you to behave foolishly.”

But Graeber’s book doesn’t just present human idiocy in its bureaucratic form. Its main purpose is to free us from a rightwing misconception about bureaucracy. Ever since Ronald Reagan said: “The most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help”, it has been commonplace to assume that bureaucracy means government. Wrong, Graeber argues. “If you go to the Mac store and somebody says: ‘I’m sorry, it’s obvious that what needs to happen here is you need a new screen, but you’re still going to have to wait a week to speak to the expert’, you don’t say ‘Oh damn bureaucrats’, even though that’s what it is – classic bureaucratic procedure. We’ve been propagandised into believing that bureaucracy means civil servants. Capitalism isn’t supposed to create meaningless positions. The last thing a profit-seeking firm is going to do is shell out money to workers they don’t really need to employ. Still, somehow, it happens.”

Graeber’s argument is similar to one he made in a 2013 article called “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs”, in which he argued that, in 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that by the end of the century technology would have advanced sufficiently that in countries such as the UK and the US we’d be on 15-hour weeks. “In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshalled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. Huge swaths of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they believe to be unnecessary. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it.”

Which jobs are bullshit? “A world without teachers or dock-workers would soon be in trouble. But it’s not entirely clear how humanity would suffer were all private equity CEOs, lobbyists, PR researchers, actuaries, telemarketers, bailiffs or legal consultants to similarly vanish.” He concedes that some might argue that his own work is meaningless. “There can be no objective measure of social value,” he says emolliently.

In The Utopia of Rules, Graeber goes further in his analysis of what went wrong. Technological advance was supposed to result in us teleporting to new planets, wasn’t it? He lists some of the other predicted technological wonders he’s disappointed don’t exist: flying cars, suspended animation, immortality drugs, androids, colonies on Mars. “Speaking as someone who was eight years old at the time of the Apollo moon landing, I have clear memories of calculating that I would be 39 years of age in the magic year 2000, and wondering what the world around me would be like. Did I honestly expect I would be living in a world of such wonders? Of course. Do I feel cheated now? Absolutely.”

But what happened between the Apollo moon landing and now? Graeber’s theory is that in the late 1960s and early 1970s there was mounting fear about a society of hippie proles with too much time on their hands. “The ruling class had a freak out about robots replacing all the workers. There was a general feeling that ‘My God, if it’s bad now with the hippies, imagine what it’ll be like if the entire working class becomes unemployed.’ You never know how conscious it was but decisions were made about research priorities.” Consider, he suggests, medicine and the life sciences since the late 1960s. “Cancer? No, that’s still here.” Instead, the most dramatic breakthroughs have been with drugs such as Ritalin, Zoloft and Prozac – all of which, Graeber writes, are “tailor-made, one might say, so that these new professional demands don’t drive us completely, dysfunctionally, crazy”.

His bullshit jobs argument could be taken as a counterblast to the hyper-capitalist dystopia argument wherein the robots take over and humans are busted down to an eternity of playing Minecraft. Summarising predictions in recent futurological literature, John Lanchester has written: “There’s capital, doing better than ever; the robots, doing all the work; and the great mass of humanity, doing not much but having fun playing with its gadgets.” Lanchester drew attention to a league table drawn up by two Oxford economists of 702 jobs that might be better done by robots: at number one (most safe) were recreational therapists; at 702 (least safe) were telemarketers. Anthropologists, Graeber might be pleased to know, came in at 39, so he needn’t start burnishing his resume just yet – he’s much safer than writers (123) and editors (140).

Graeber believes that since the 1970s there has been a shift from technologies based on realising alternative futures to investment technologies that favoured labour discipline and social control. Hence the internet. “The control is so ubiquitous that we don’t see it.” We don’t see, either, how the threat of violence underpins society, he claims. “The rarity with which the truncheons appear just helps to make violence harder to see,” he writes.

In 2011, at New York’s Zuccotti Park, he became involved in Occupy Wall Street, which he describes as an “experiment in a post-bureaucratic society”. He was responsible for the slogan “We are the 99%”. “We wanted to demonstrate we could do all the services that social service providers do without endless bureaucracy. In fact at one point at Zuccotti Park there was a giant plastic garbage bag that had $800,000 in it. People kept giving us money but we weren’t going to put it in the bank. You have all these rules and regulations. And Occupy Wall Street can’t have a bank account. I always say the principle of direct action is the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.”

He quotes with approval the anarchist collective Crimethinc: “Putting yourself in new situations constantly is the only way to ensure that you make your decisions unencumbered by the nature of habit, law, custom or prejudice – and it’s up to you to create the situations.” Academia was, he muses, once a haven for oddballs – it was one of the reasons he went into it. “It was a place of refuge. Not any more. Now, if you can’t act a little like a professional executive, you can kiss goodbye to the idea of an academic career.”

Why is that so terrible? “It means we’re taking a very large percentage of the greatest creative talent in our society and telling them to go to hell … The eccentrics have been drummed out of all institutions.” Well, perhaps not all of them. “I am an offbeat person. I am one of those guys who wouldn’t be allowed in the academy these days.” Indeed, he claims to have been blackballed by the American academy and found refuge in Britain. In 2005, he went on a year’s sabbatical from Yale, “and did a lot of direct action and was in the media”. When he returned he was, he says, snubbed by colleagues and did not have his contract renewed. Why? Partly, he believes, because his countercultural activities were an embarrassment to Yale.

Born in 1961 to working-class Jewish parents in New York, Graeber had a radical heritage. His father, Kenneth, was a plate stripper who fought in the Spanish civil war, and his mother, Ruth, was a garment worker who played the lead role in Pins and Needles, a 1930s musical revue staged by the international Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

Their son was calling himself an anarchist at the age of 16, but only got heavily involved in politics in 1999 when he became part of the protests against the World Trade Organisation meeting in Seattle. Later, while teaching at Yale, he joined the activists, artists and pranksters of the Direct Action Network in New York. Would he have got further at Yale if he hadn’t been an anarchist? “Maybe. I guess I had two strikes against me. One, I seemed to be enjoying my work too much. Plus I’m from the wrong class: I come from a working-class background.” The US’s loss is the UK’s gain: Graeber became a reader in anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London, in 2008 and professor at the LSE two years ago.

His publications include Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (2004), in which he laid out his vision of how society might be organised on less alienating lines, and Direct Action: An Ethnography (2009), a study of the global justice movement. In 2013, he wrote his most popularly political book yet, The Democracy Project. “I wanted it to be called ‘As if We Were Already Free’,” he tells me. “And the publishers laughed at me – a subjunctive in the title!” But it was Debt: The First 5,000 Years, published in 2011, that made him famous and has drawn praise from the likes of Thomas Piketty and Russell Brand. Financial Times journalist and fellow anthropologist Gillian Tett argued that the book was “not just thought-provoking but exceedingly timely”, not least, no doubt, because in it Graeber called for a biblical-style “jubilee”, meaning a wiping out of sovereign and consumer debts.

At the end of The Utopia of Rules, Graeber distinguishes between play and games – the former involving free‑form creativity, the latter requiring participants to abide by rules. While there is pleasure in the latter (it is, to quote from the subtitle of the book, one of the secret joys of bureaucracy), it is the former that excites him as an antidote to our form‑filling red-taped society.

Just before he finishes his dinner, Graeber tells me about the new idea he’s toying with. “It’s about the play principle in nature. Usually, he argues, we project agency to nature insofar as there is some kind of economic interest. Hence, for instance, Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene. I begin to understand the idea better– it’s an anarchist theory of organisation starting with insects and animals and proceeding to humans. He is suggesting that, instead of being rule-following economic drones of capitalism, we are essentially playful. The most basic level of being is play rather than economics, fun rather than rules, goofing around rather than filling in forms. Graeber himself certainly seems to be having more fun than seems proper for a respected professor.

The Utopia of Rules is published by Melville House

+–+

Here, The Never Was a West: and other essays, photocopied PDF,

Click to access graeber_there-never-was-a-west.pdf

Quick analysis of The Never Was a West,

David Graeber: There never was a West! Democracy as Interstitial Cosmopolitanism

by lorenz on Apr 21, 2006 in politics, Us and Them, globalisation, journal articles / papers, cosmopolitanism

(LINKS UPDATED 20.8.2020) Recently, the terms “Western civilisation” or “Western values” have been used in opposition to regimes mainly in the Middle East. But how fruitful is this notion of “the West”? In his keynote speech at the conference Cosmopolitanism and Anthropology, David Graeber showed that this idea is a kind of Othering: It makes artificial gaps between people that have more in common than supposed.

His deconstruction of the West resembels earlier deconstructions of the National (what traditionally has been considered as “typical Norwegian” is rather the result of migration and influences from other countries).

In his paper that he presented on the conference, Graeber writes:

“If you examine these terms more closely, however, it becomes obvious that all these “Western” objects are the products of endless entanglements. “Western science” was patched together out of discoveries made on many continents, and is now largely produced by non- Westerners. “Western consumer goods” were always drawn from materials taken from all over the world, many explicitly imitated Asian products, and nowadays, most are produced in China.

(…)

As European states expanded and the Atlantic system came to encompass the world, all sorts of global influences appear to have coalesced in European capitals, and to have been reabsorbed within the tradition that eventually came to be known as “Western”.

(…)

Can we say the same of “Western freedoms”? The reader can probably guess what my answer is likely to be.”

The idea of a superior “Western civilisation” is a product of colonialism. But as he says:

“Opposition to European expansion in much of the world, even quite early on, appears to have been carried out in the name of “Western values” that the Europeans in question did not yet even have.”

Graeber mainly used the notion of democracy as a Western concept as an example:

“Almost everyone who writes on the subject assumes “democracy” is a “Western” concept begins its history in ancient Athens, and that what 18th and 19th century politicians began reviving in Western Europe and North America was essentially the same thing.

(…)

Democratic practices-processes of egalitarian decision-making-however occur pretty much anywhere, and are not peculiar to any one given “civilization”, culture, or tradition.”

We should according to Graeber treat the history of “democracy” as more than just the history of the word “democracy”:

“If democracy is simply a matter of communities managing their own affairs through an open and relatively egalitarian process of public discussion, there is no reason why egalitarian forms of decision-making in rural communities in Africa or Brazil should not be at least as worthy of the name as the constitutional systems that govern most nation-states today-and in many cases, probably a good deal more so.

(…)

Rather than seeing Indian, or Malagasy, or Tswana, or Maya claims to being part of an inherently democratic tradition as an attempt to ape the West, it seems to me, we are looking at different aspects of the same planetary process: a crystallization of longstanding democratic practices in the formation of a global system, in which ideas were flying back and forth in all directions, and the gradual, usually grudging adoption of some by ruling elites.

Yet why have these procedures not been considered as “democratic.” The main reason in Graebers view: In these assemblies, things never actually came to a vote! Rather, they preferred “the apparently much more difficult task” of coming to decisions “that no one finds so violently objectionable that they are not willing at least assent”. It is this form of participatory democracy that social movements around the world are trying to revive!”

Graeber also discusses the “coercive nature of the state” and the contradictions that democratic constitutions are founded on. He refers to Walter Benjamin (1978) who pointed out “that any legal order that claims a monopoly of the use of violence has to be founded by some power other than itself, which inevitably means, by acts that were illegal according to whatever system of law came before it”.

And about Ancient Greece and democracy:

“It is of obvious relevance that Ancient Greece was one of the most competitive societies known to history. It was a society that tended to make everything into a public contest, from athletics to philosophy or tragic drama or just about anything else. So it might not seem entirely surprising they made political decision-making into a public contest as well. Even more crucial though was the fact that decisions were made by a populace in arms.”

This article was amended on 21 March 2015, to correct a spelling error in the headline.

LikeLike